How Did a COVID-19 Eviction Moratorium Affect Household Well-Being?

How Did a COVID-19 Eviction Moratorium Affect Household Well-Being?

- UCLA Anderson Distinguished Professor of Finance Stuart Gabriel studied the consequences of a nationwide eviction moratorium

- Evidence shows that renters not threatened with eviction redirect spending to immediate food and grocery needs

- Data indicate that moratoria on eviction reduce food insecurity and alleviate mental distress

- Black households are disproportionately affected by the consequences of eviction threat

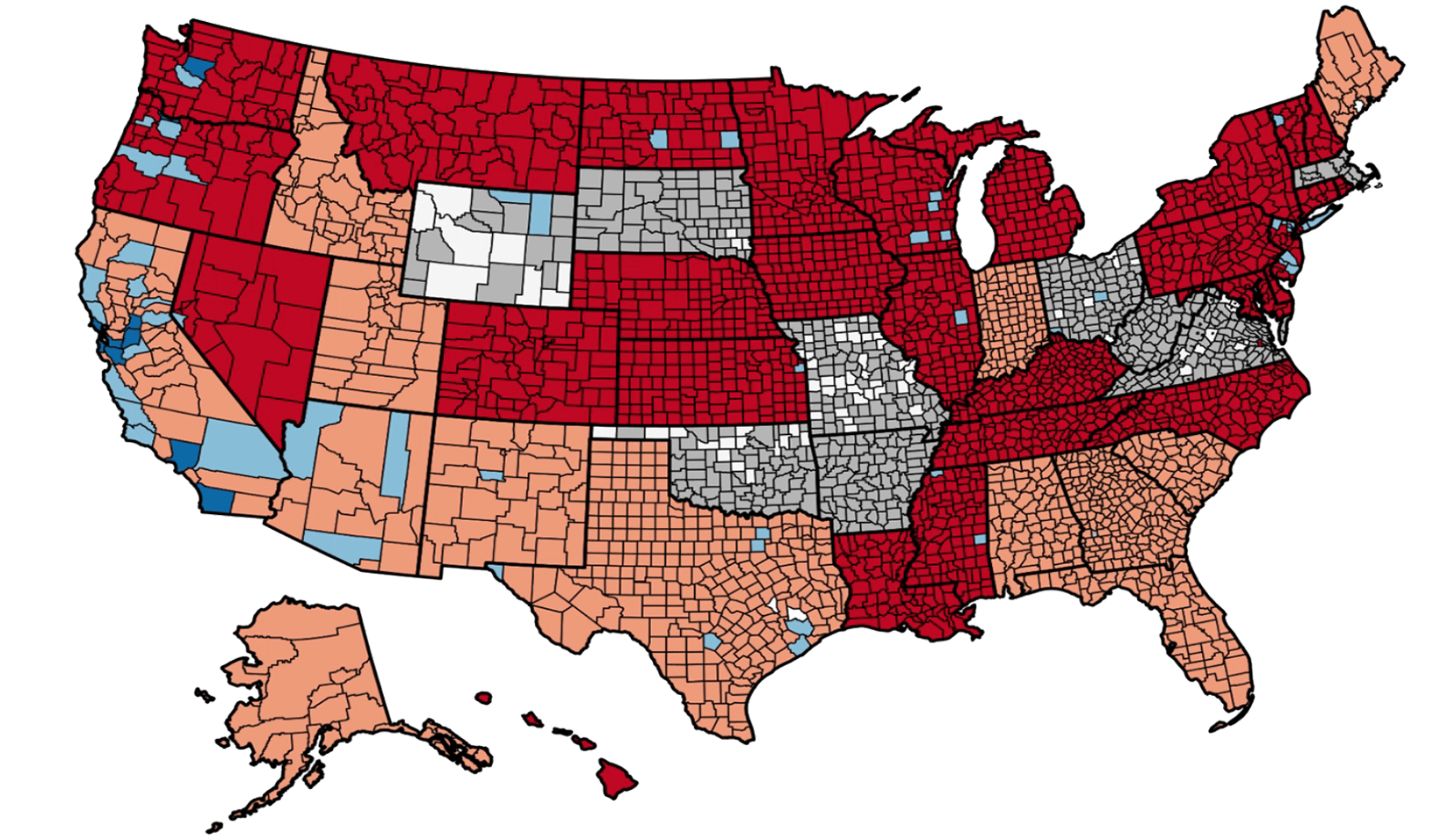

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed an estimated 17 million U.S. households to eviction risk. Meanwhile, upward of $70 billion in outstanding rent debt was owed to landlords at the end of 2020. New research co-authored by UCLA Anderson Distinguished Professor of Finance Stuart Gabriel, Arden Realty Chair and faculty director of the UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate, is among the first studies to provide evidence of how the prospect of eviction amid pandemic adversely affects household spending and debt, food security and mental health outcomes. Gabriel and his co-authors conclude that the combination of nationwide moratoria on evictions and expansive fiscal and monetary stimulus will accelerate economic recovery and put renter households back to work.

Through its Howard and Irene Levine Affordable Housing Development Program, Housing as Health Care Initiative and other research-based efforts, the Ziman Center connects academicians, industry and community leaders, policymakers and students to promote a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to meeting challenges faced by communities.

Policy interventions sometimes have intended consequences and often have unintended consequences. Based on some of our prior research, we suspected that the relatively unprecedented imposition of moratoria on rental eviction could actually have both adverse as well as broad beneficial consequences.

There are a lot of reasons to put a moratorium on rental evictions. Probe a little bit further and you ask “Where would people go if they were evicted in the middle of a pandemic shutdown order? Would there be other units open to them? Would they fall into homelessness? What are the typical resources of a renter household?”

Turns out the resources of a rental household are what you might call de minimis. The typical net worth of a homeowner in this country is a quarter million dollars. The typical net worth of a renter is $5,000 dollars. So, renters live right on the financial edge. And if they have a choice between paying rent and buying food, they may be forced to forgo some of their caloric intake.

We ask the question whether the benefits of eviction moratorium could go beyond the immediate imperative of providing shelter from the pandemic storm. We looked at things that were going on around us in the midst of the pandemic shut-down periods. We were seeing people lined up for miles upon miles at major raceways around the country and elsewhere for a couple bags of groceries. It was extremely concerning to us. We, as economists, know as well that there are major correlations between adverse economic shocks and population health. During the Great Depression, suicide rates went up, people jumped out of buildings. Lack of work, lack of income, indebtedness — these are all very detrimental to health generally, and detrimental to mental health specifically.

Take a standard renter household with limited financial resources. We were wondering if an eviction moratorium law allows you to defer your rent payment, and it allows you to stay in your place of shelter, could this benefit your well-being in other ways? We looked at a broad-based set of measures of food scarcity that we obtained from specific pandemic surveys as well as search-based measures of food insecurity. We looked at evidence of changes in mental health.

In undertaking the analysis, a set of statistical results emerged to support our hypothesis. The data indicate that households who benefited from rental eviction moratoria do have at least limited liquidity, and that can go to support necessary consumer spending — including on grocery items. We also found that rental eviction moratoria were associated with reductions in household food insecurity and alleviation of mental duress. These were statistical results we identified in the data and held to a very high level of methodological protocol.

When you impose a rental eviction moratorium, you’re imposing winners and losers. Another way of saying this is exigency: The pandemic was a “black swan” emergency event and it called for an emergency response. With moratoria on evictions, renters may win over some brief period of time, but landlords may lose. They’re not collecting rent. It turns out that not all those landlords are billion-dollar public companies. Many of them are just individuals who own a rental unit and are in danger of defaulting on their own mortgage when they don’t have that rental cashflow coming in. We know that our economic system could not sustain a long-standing rental eviction moratorium. It would bring the entire system to a grinding halt.

Evictions aren’t rampant, but they are not unusual. They’re more common among African American households, for example. And there is substantial literature showing adverse household legal, economic, child-raising and health consequences of eviction.

Another piece to this story is how landlords would have benefited eviction in the absence of such moratoria. That’s not something we go into deeply in this particular paper, but the “plain vanilla” economic story here is, you evict someone who’s not paying the rent, you replace them the next day with someone who is, and you keep your cashflow relatively intact. But if we’re in the middle of a pandemic, how in the world are you replacing that family with someone who just happens to be moving and looking for an apartment in the middle of a shutdown order. It’s arguable, at least for a short-run rental eviction moratorium, that losses to landlords are not as great as potentially claimed. They’re going to make it up somewhat down the road because none of these eviction moratoria say “rent forgiveness,” they all say “rent defer.” And it now appears that the recent fiscal relief bill signed into law will assist in paying back rent to landlords on a selective basis.

I’ve been teaching MBA students for much of my career. MBA students are not exactly the same as they used to be. Prior to the 2000s financial crisis, pretty much the modus operandi of MBA students was, how do I go out into the world and make more money? That changed with the last financial crisis. And it’s evolving currently.

So many corporate entities and public institutions around the country, and even around the world, have newfound and deep concerns and convictions that relate to a whole slew of issues that come under the headings of social impact and social justice. Our students bring those values into the classroom. They bring those career aspirations to the school and leave with new insights and skill sets that allow attention to career undertakings with multiple bottom lines. Whereas one bottom line might be what’s good for them personally in their career, a second bottom line might be, how do I contribute to this society? How do I create opportunity for others? The third bottom line relates to environmental justice and climate change. At the Ziman Center, at UCLA Anderson and at UCLA more generally, we also are seeking multiple bottom lines.

I’ve spent the better part of my career combining real estate research with issues of social and public policy, and it’s just been an incredibly satisfying thing to do. I have to be hopeful.

The role of academics, the role of academic research, is to shine the light. As academics, we’re not in the pockets of special interests. In this research, we cover a piece of the story that, once you read it, probably seems reasonable. But what we showed was that there’s a piece of the story that wasn’t being discussed, that wasn’t known, that wasn’t statistically validated before. So now we have some data and some analysis that say, in an emergency situation, you impose a rental eviction moratorium and there may be other external effects that are quite beneficial, right at that emergency point in time.

My personal view is that the best research involves not only the best data and the best method and the best technique, but also topics of social and economic significance. In other words, topics that mean something in the broader societal context. I think if you spoke to the best economists in the world and you looked at the papers that they published, you would see that they addressed issues of real societal consequence. The reason I came into economics was that I was interested in public policy. So, for me, it’s the public policy interest that’s driving economics, not vice versa. I’ve tried in my career to research topics that I think are societally consequential.