Our Legacy

One day in 1958, the phone rang at Werner Renberg's home. Was it a crank call? Renberg felt he had no choice but to respond with biting sarcasm.

"This is Gerald Loeb," the man on the other end of the line said.

"I thought he was pulling my leg. Mr. Loeb was very well known back then, an author of a best seller," Renberg says. The mystery man told Renberg that he had just won the inaugural Gerald M. Loeb award for distinguished business and financial journalism in the magazine category.

"My initial reaction was something like someone saying, 'This is Santa Claus.' Yeah, and I'm Mrs. Claus," Renberg says. Mr. Loeb was not pulling the Oklahoma native's leg.

Renberg soon got a formal letter of congratulations from the dean of the business school at the University of Connecticut. Weeks later, Renberg found himself sitting with Mr. Loeb, members of the judging committee, and David Steinberg, reporter at the Herald Tribune and winner of the newspaper category, while having lunch in a ballroom at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in Manhattan.

Steinberg passed away this spring.

To say that Renberg was surprised to hear he had won the award may be an understatement. His bosses at Business Week hadn't bothered to tell him they'd submitted an entry. But the magazine certainly took the competition seriously.

According to Renberg, the publisher's office submitted a collection of eight articles that focused on the theme of regional economic development and cooperation between the public and private sectors.

At the time, Renberg was head of a one-man "regions" department. The articles featured how business people, municipal leaders and labor unions joined hands in working to boost the economy. The articles covered regions including Dallas- Ft. Worth, St. Louis, and Newark, N.J. Renberg recalls penning three or four of the pieces and commissioning the others to freelance writers.

"We were very proud of the award at McGraw-Hill," Renberg says, referring to the former owner of the magazine. "We had beaten Fortune, Harvard Business Review, Time, Life, Barron's Newsweek and Dun's Review.

"To fully appreciate the significance of a Loeb award for business and financial writing in newspapers and magazines, one has to recall the few awards available to business and financial journalists when it was created," Renberg adds.

He vaguely recalls a separate award that was sponsored by a trade organization, but can't remember whether there were any awards that had the backing of The Associated Press Managing Editors Association, business journalist organizations, or Sigma Delta Chi, a fraternity for news writers.

"For sure there was no Pulitzer, and I believe there is none yet," he says.

Today, we clearly know why Loeb began the awards.

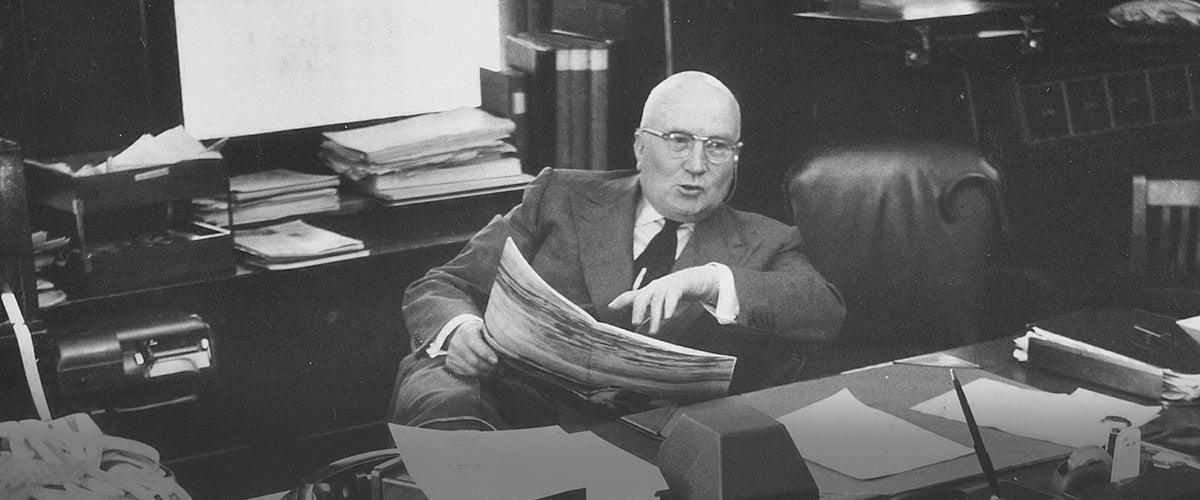

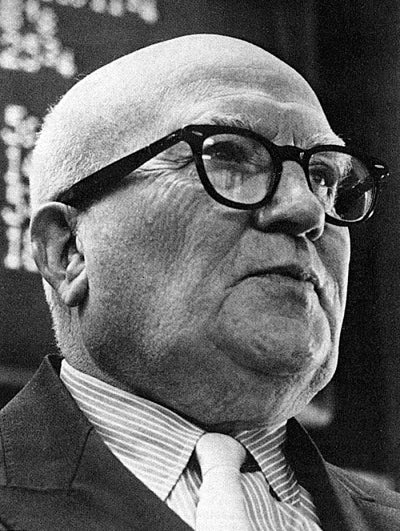

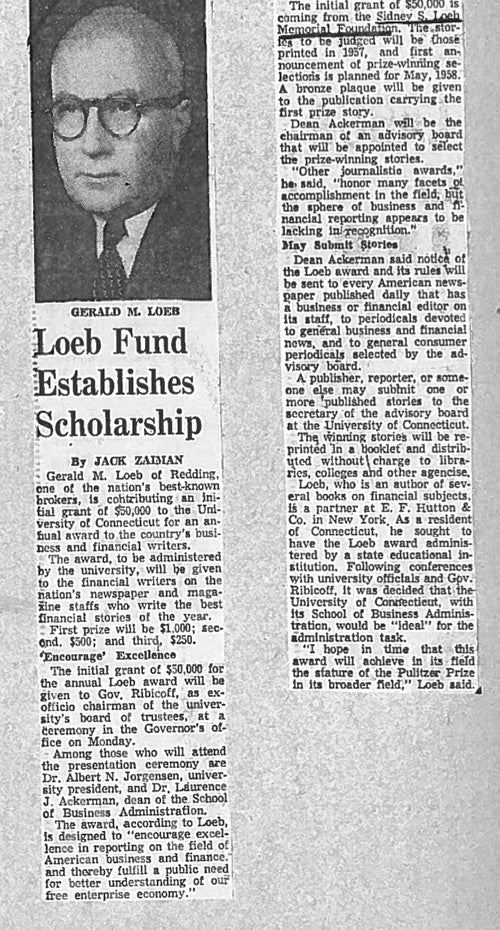

On its website, the UCLA Anderson School of Management writes that "his intention was to encourage reporting on business and finance that would inform and protect the private investor and the general public." Harold Williams, a former commissioner of the Securities & Exchange Commission and dean of the UCLA business school back in 1973 when Loeb (1899-1974) decided to move the home of the awards from University of Connecticut to the west coast institution, offered a second reason.

"The eld of nancial journalism is changing and continues to change dramatically," Williams was quoted as saying in an article by Amanda Andonian. "In order to live up to what Gerald had in mind, I think it's the responsibility of those leading The Loeb Awards to change with it."

Change indeed. Today, journalists across the country compete in 12 categories, spanning from breaking news to commentary to international topics.

Still, one has to ask: Why did Loeb have such vision that others on Wall Street did not? Why did he have as much passion for good writing as he did for buying and selling common stocks with great success?

A deeper dive into Loeb's life may help provide the beginning of a complete answer.

Werner Renberg, Business Week regions editor, Loeb Awards winner in magazine field, receives $1,000 check and bronze plaque from Dr. Albert N. Jorgensen, University of Connecticut president.

1958 - Magazines - Business Week

"Cooperation of Businessmen and Municipal Government"

Loeb was born into wealth, but he quickly learned how wealth can vanish fast.

His father sold a thriving wine retailing business in New Orleans and moved to the west coast in search of new riches. Loeb’s maternal grandfather made a fortune by investing in silver in Nevada, then shifted his winnings into real estate in the Bay Area. However, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake struck a big blow. Two years later, Loeb’s father and grandfather died within two weeks of each other.

“Gone, too, was the fancy Loeb home in San Francisco with its maid upstairs, maid downstairs, cook, nurse, gardener, coachman, and the beautiful coach with the two handsome horses,” the prolific Ralph G. Martin wrote in “The Wizard of Wall Street: The Story of Gerald M. Loeb.”

Forced to live in a boarding house with his widowed mother and younger brother, Loeb then suffered polio at age 11. But the illness couldn’t stamp out a deep desire to learn through books and childhood mentors.

Loeb gave up on a dream to become an architect. But a decent-sized inheritance sparked a strong interest in investing, and he apparently got hooked at age 21 when he decided to invest his $13,000 inheritance in a corporate bond. That wad of cash was originally $75,000, to be divided equally by Loeb and his brother. But family friends who were asked by Loeb’s mother to manage the stake ended up losing nearly two thirds of it.

“I didn’t know a stock from a bond, and the first purchase I made was a very silly one,” Loeb was quoted as saying to Martin. “I saw an ad for S.W. Straus Real Estate Bonds, and the thing that sold me was their slogan, ‘Six percent for safety. . . 36 years invested without a loss to any investor.’”

Impressed by pictures of fancy buildings that the bond sellers apparently invested, Loeb immediately bought a $1,000 face-value security that matured in 15 years, “without asking anybody’s advice, without checking into the company.”

According to Martin, Loeb’s biographer, Loeb later sensed something was amiss with the investment. He redeemed the bond within a year for a small loss.

Little did he know how poorly S.W. Straus had managed proceeds from the bonds. Since the bond didn’t trade on any exchange, the market price was completely arbitrary. The bond managers could afford to pay a 6% coupon because big profits from the sale of the bonds could offset the obligations to bond holders and any small investment losses year to year.

Martin wrote that if the bond had traded on an open market, investors would’ve demanded a much higher interest rate to compensate for the high risk.

Eventually, bond holders got wiped out years later after the Strauss-owned properties plunged in value.

David Steinberg, Herald-Tribune, receives $1,000 check and bronze plaque for best Loeb Awards newspaper entry from Dr. Albert N. Jorgensen, University of Connecticut president.

1958 - Newspapers - New York Herald Tribune

"Corporate Management: Its Effect on the Public Security"

Loeb Fund Establishes Scholarship

Loeb got lucky. Yet it was the second bond investment that helped shape Loeb’s values in working on Wall Street.

His father’s friend was senior partner at a respected brokerage in San Francisco. One day, Loeb showed up and asked the man what he should buy. The broker presented a security across the pond in the U.K. that was payable either in sterling or U.S. dollars. He also provided the young Loeb with a wealth of information on how bonds are sold, how ownership is recorded, and the exact commission (a small one in this case) earned by the broker.

It was a watershed moment in Loeb’s life and future career as a broker and investment adviser.

“The first bond was sold to me,” Loeb said. “It was sold by the advertisement I read, it was sold by the fancy literature they gave me, and it was sold by the salesman who really finally sold it to me. But that second bond, I bought.”

That same year, when Loeb was 21, he jumped into the world of investments. His first stint as a bond salesman didn’t last long. The boss chewed him out for refusing to push a high-risk debt security to his first client, a doctor, even though it meant a fat commission for the bond house. But it was still early in the roaring ‘20s. Loeb quickly found another job at McDonnell & Co., described by Martin as “a first-class brokerage member of the New York Stock Exchange.”

“First class” didn’t necessarily mean the brokerage was big. Loeb soon found himself not only assisting the sole bond trader, the lone equity man, and the single statistician, but also helping filling customers’ transactions.

While at McDonnell, Loeb was still a few jobs away from landing his first position at E.F. Hutton. But a request from The San Francisco Call & Post to write an article about government-issued Liberty Bonds likely opened the door to another feather in his hat, that of being a highly influential and popular writer.

Martin notes that Loeb initially simply rewrote reports from bond rating companies Moody’s and Standard Statistics, which later became known as Standard & Poor’s. But after he got that byline, more requests came his way.

“Those early articles told about an automobile company making farm machinery and telling something of the company history and how much dividend they paid, basic business news that anybody could have written, but nobody did,” Loeb said.

Learning to write for the masses about a complex subject perhaps helped Loeb develop a direct, factual, and persuasive style of writing. Pick virtually any page in his two big hits, “The Battle for Investment Survival” in 1935 and “The Battle for Stock Market Profits (Not the way it’s taught at Harvard Business School)” in 1971, and you immediately understand why his writings still capture the attention of serious investors today.

He began the first book with brutal honesty.

“Nothing is more difficult, I truly believe, than consistently and fairly profiting in Wall Street,” he writes in the start of chapter one in “Battle for Investment Survival. “I know of nothing harder to learn. Schools and textbooks supply only a good theoretical background.”

Loeb avoided long-winded passages. Instead he favored serving pieces of Wall Street wisdom in small attractive bites. The 1965 revised edition of “Investment Survival” contains 78 chapters, including a lengthy postscript, and each chapter is rarely more than ve pages.

The Simon & Schuster first edition of “Stock Market Profits” has 116 chapters, neatly housed within 347 pages.

Another unique element? In his books, Loeb freely used first-and second-person perspective. It worked. No droll classroom lecture. Instead, a reader could feel he or she was sitting in a nice leather chair next to Loeb and a warm replace, learning the art and science of picking winning stocks.

How big a hit was “Battle for Investment Survival?” Big enough for Loeb to ultimately oversee 10 revised editions of that initial 1935 printing.

Read “Battle for Stock Market Profits” carefully, and you learn the highly-valued Loeb principles of lling out a detailed checklist before each investment, being ready to make a 180-degree turn in the market when it’s necessary, and taking a contrarian stance.

Loeb makes these points:

Buy high, sell higher.

In Chapter 18, “Stock Market Discipline,” Loeb writes, “The safest investments of all are more often than not in stocks that have gone up, are going up, seem high, but continue to go up.”

“The really good stocks almost always seem overpriced. It requires discipline to make yourself pass up the low-priced “bargain” and buy seemingly high-priced growth.”

Don’t diversify simply by asset class.

“If you invest all your funds at once, you must be very expert to select just the right time,” Loeb wrote. “If you hold funds back and invest a fraction, say 10 percent, or 20 percent when available, and a second fraction a month or two or three later or on some seemingly favorable market juncture, you reduce risk.”

In other words, use time as a way to diversify.

Markets are irrational. Loeb learned from other investing pros, such as Bernard Baruch, about how important it is to be aware of the madness of crowds, and passed it along. I think being contrary successfully is being late, he wrote. The man who shes for the bottom or reaches for the top is never the winner. Keep your contrariness under wraps until you think you sense the exhaustion of the trend.

As he illustrated in chapter 21, “Contrary Opinion as a Tool in Stock Selection,” Loeb knew the mighty strength of the market and encouraged others to be humble. “When the crowd takes the bit in the teeth, price movements always go to excess. There is an old stock exchange proverb: ‘No price is too low for a bear or too high for a bull.’”

Always have an exit strategy.

“It is usually better to err in selling too soon than not to sell at all,” Loeb wrote. “One of the considerations in determining a selling spot is to sell on great strength and not wait for trouble to spur you to liquidate.”

Loeb found an edge in Wall Street with charts. He stopped short of saying that any stock chart gave an absolute exit point for every investor. But in chapter 20, “Do Something About Selling,” he made it clear that investors need to make critical decisions on cold facts, not on hot emotions. So he advised, “to consider selling any stock which reacts 10 to 15 percent from its top.”

O’Neil has said he once met with Loeb to ask if he always sold a stock if it fell 10% below the purchase price. Loeb was said to have replied that he hoped to be out of such a losing position well before that.

“I think meeting Loeb made a big impact on Bill O’Neil,” Bryan Anderson, market strategist at Austin-based Beck Capital Management, told IBD in an article published in December of 2016. “Loeb had great personal qualities. He valued honesty. He valued exibility of thinking and being unbiased.”

Loeb’s influence and respect among futures traders is no less deep.

Victor Niederhoffer wrote in “The Education of a Speculator” about how he learned from some traders the need to be courageous and buy when a country’s stock exchange was in turmoil or even closed for business, or when large brokerages were in trouble. The global macro trader, who once worked for hedge fund manager George Soros, also pointed to an anecdote from Loeb on reasons for caution when times for brokers were extremely good.

“Gerald Loeb recounts a story illustrating the other side of the equation. His brokerage house was swimming in luxury at the height of the 1929 crash, ‘Niederhoffer wrote. “Loeb recommends selling stocks when brokerage profits are high and buying them when brokerages houses are in the red.”

Niederhoffer er added another Loeb anecdote about Mike Meehan, who handled trading on the floor of the NYSE for the highflier RCA, opened the first office on a steamship, the Bremen, a luxury liner from northern Germany.

Loeb took what he believed to be the maiden voyage of that brokerage office while sailing to Europe in early October 1929. And the rest is history.

The Mission of Investor's Business Daily

IBD’s approach is based on over 50 years of objective and exhaustive research. It started when IBD’s founder, William J. O’Neil, began studying the best stocks of all time and discovered seven common traits these stocks displayed just before they made their biggest gains. Each letter in CAN SLIM stands for one of these seven traits. All of IBD’s products and features are based on this top-performing system.

You’ll often see investing products focus on either fundamental or technical analysis. IBD’s research shows that to truly succeed in the market, you need both to get the complete picture.