UCLA Anderson’s Storied Art Collection Has a Steward

UCLA Anderson’s Storied Art Collection Has a Steward

Professor Emeritus Don Morrison’s interest in art stems from his college days at MIT

March 27, 2024

- Professor Emeritus Donald Morrison is the unofficial curator of UCLA Anderson’s art collection

- The noted marketing researcher and applied statistics expert happens also to take a keen interest in modern and contemporary art

- Morrison has forged cross-campus alliances and cultivated relationships with colleagues and donors over the 36 years he’s taught at Anderson

On the score of public art on U.S. university campuses, MIT has its grand Alexander Calder stabile, University of Chicago its famous Henry Moore and Bard College a stunning permanent installation by Olafur Eliasson. Rodin’s sculpture The Thinker sits in contemplation at Stanford, Columbia and University of Kentucky, to name a few.

UCLA’s Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden boasts works by Calder, Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Hans Arp, among many others. On permanent view are a Rodin — though, refreshingly, his less sedentary Walking Man — and one of Richard Serra’s Torqued Ellipses, commissioned for the campus by Eli Broad and installed (all 42 tons of it) in 2006.

But in addition to UCLA’s outdoor sculptures and the world-class collections of the Hammer and Fowler museums, art abounds within the UCLA Anderson School of Management complex — a “campus within a campus” that is itself a monumental sculptural work by architects Pei Cobb Freed & Partners.

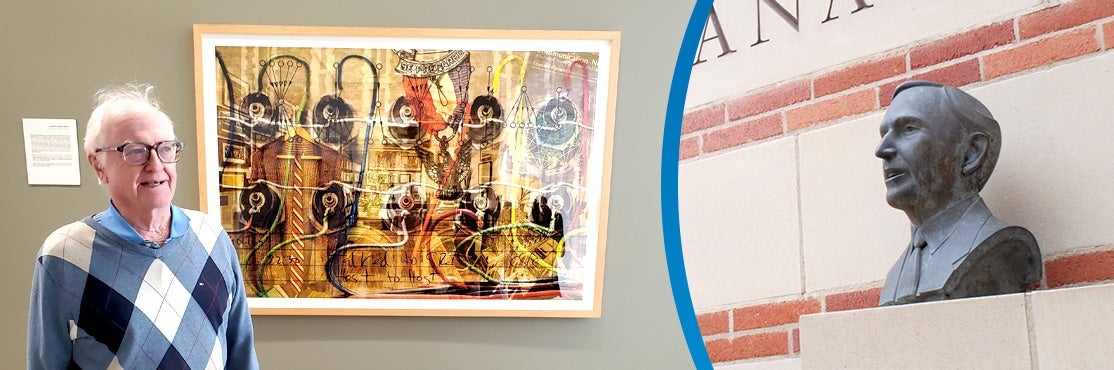

The collection is a combination of donations and loans, plus three pieces Anderson rented from the erstwhile Armand Hammer Museum rental gallery in anticipation of the 1995 opening of the school’s current complex. UCLA Anderson’s Professor Emeritus Donald Morrison — noted marketing researcher, applied statistics expert and namesake, with his family, of the Morrison Center for Marketing and Data Analytics — is, among so many other things Bruin, the “unofficial” curator of Anderson’s art collection.

Each of Anderson’s seven buildings, including Rosenfeld Library and the new Marion Anderson Hall, showcases original works ranging from limited-edition prints to large-scale canvases to sculpture in a variety of media. With the exception of signed Picasso serigraphs and a few pieces staff and faculty are lucky enough to display in their offices, they’re all accessible to view in person, and all somehow linked to Morrison’s stewardship of the collection and his many friendships among Anderson administrators, campus colleagues and fellow university supporters.

Visitors to Anderson’s Gold Hall, Entrepreneurs Hall and Cornell Hall will be reminded that, in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, Venice Beach was a mecca for some of the most critically acclaimed talent in the modern art canon. Larry Bell’s Ground Plane, donated by fine art advisor Cecelia Dan, typifies the artist’s 1990s explorations in mixed media. Bell, a member of the original stable of Los Angeles’ Ferus Gallery, where he staged his first solo exhibition in 1962, is still active in his Venice and Taos, New Mexico, studios. Notable pieces donated by the Budge and Brenda Offer Collection include Sam Francis’ Meteorite, an abstract screenprint produced in 1986 at the iconic Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles. “A lot of people think Manhattan was producing all the art,” says Morrison. “But the Pasadena Art Institute, predecessor to the Norton Simon Museum, was showing some abstract expressionist artists before New York was. And even among East Coast artists, the most prestigious printers were out here in Los Angeles.” The Offers also donated Portrait of Jenny, a 1991 acrylic on canvas by quintessential California artist Billy Al Bengston, another early Ferus star.

Early Attraction

To hear Morrison tell it, he came to the position of curator serendipitously and voluntarily. But behind his nonchalance lies a keen interest in art and, just as important, artists and fellow appreciators of art. It started in college at MIT when Morrison began to notice art on campus. MIT’s motivation to display public art following WWII was, in part, to “humanize” scientists and the sciences. Business played its role, too: Donations to the university from Standard Oil in 1951 formed the basis of MIT List Center’s museum collections. Morrison, who was a mechanical engineering undergraduate, says the art he saw on campus took his head out of numbers, formulas and athletics as he rushed between math and science classes. His graduation from MIT predates the installation of Calder’s famous La Grande Voile (1965), but his awareness of art was seeded.

With his wife Sherie, a UCLA distinguished research professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics who holds patents in antibody technology, Morrison began collecting art the couple could afford on salaries paid to junior professors at Columbia University in the 1970s. Fast-forward to their arrival in California in the late 1980s, when the Morrisons began collecting in earnest, and Don became inspired to involve himself more directly with artists and galleries up and down the West Coast. He cherishes a personal connection to Venice-based artist Laddie John Dill, a central figure in the California light and space movement who is well represented in Anderson’s collection.

Dill’s mixed media Volcanic Ridge, which hangs in the atrium of Gold Hall, is one of the three original works the school rented (and has since acquired) from the Hammer about the time Anderson’s current complex opened. The others are Dogtown No. 21, a collage of found metal mounted on steel brads titled by triple Bruin and Venice Beach mainstay Tony Berlant (B.A. ’61, M.A. ’62, MFA ’63), who taught at UCLA in the 1960s; and the large-scale abstract steel sculpture Spanish Mirrors, created by Dill’s brother Guy Dill, that greets anyone walking in the door of Collins Hall.

Community Counts

Morrison knows that in art, as in business, connections count. Because Morrison, the founding editor of Marketing Science and, with Sherie, winner of the UCLA Medal, is so good at forging and maintaining productive partnerships, Anderson’s collection has benefited from the generosity of other campus entities. His collaborations with Debby Doolittle, contracted for nearly 30 years as curator of UCLA Health’s art collection, directed several donations Morrison’s way — including Bell’s Ground Plane — when the medical school couldn’t accommodate them. (Doolittle incidentally went to school with Laddie John and Guy Dill, and once arranged a studio visit for the Morrisons and their grandchildren. The rest is art history.)

Publisher Cleon T. “Bud” Knapp, for whom Anderson’s annual venture competition is named, with his late wife Betsy collected works by living artists for decades. The Knapps generously augmented Anderson’s collection with several pieces, including James Hayward’s highly tactile (but please don’t touch it!) Homage to the Muse, a 15-panel oil and wax on canvas from 1981.

Maxine and Eugene (B.S. ’56) Rosenfeld’s legacy will be secured by the library at Anderson that bears their name, of course. But the Rosenfelds are also to be thanked for two 1970 screenprints on aluminum by Victor Vasarely and numerous other pieces they donated to Anderson’s collection, such as a 1976 hand-dyed jute tapestry by Alexander Calder that hangs at the entrance to the library. Near the library’s circulation desk, patrons can see a print from Robert Motherwell’s Basque Suite, a gift from a corporate donor.

These donations naturally bear the thumbprint of Don Morrison, who was cultivating them before Anderson’s current complex opened in 1995. “The Rosenfelds and Knapps had been friends for many years, and both had serious art collections,” says Morrison. “I approached them and said, ‘If you have any extra art, pieces in storage, we have a lot of wall space!’ That’s how we got some of those pieces.”

The Rosenfelds also donated one of Anderson’s two works by multidisciplinary artist Lita Albuquerque (B.A. ’68), who taught at Art Center for nearly 37 years and remains active internationally. They gave the school Ventura Freeway, a quintessential L.A. painting by the late Olga Seem (B.A. ’49, M.A. ’63), who famously (if speciously?) painted over an Ed Ruscha canvas that once belonged to curator and museum director Henry Hopkins. Seem’s 1977 aerial interpretation of the 101 will be appreciated by anyone familiar with that singular combination of beauty and brutality that characterizes Los Angeles sprawl.

Visitors to Anderson will notice numerous paintings on loan from Felix Denis, whose signature golden canvases shimmer, appropriately enough, throughout Gold Hall. Photographs by Jane Gottlieb (B.A. ’68) emblazon the corridors of Entrepreneurs Hall with DayGlo colors. Multiple works by Robert Weingarten, including photographs in his 6:30 a.m. series from 2003, are on loan from David and Lynn Pollock.

Weingarten himself is lending Anderson his 2013 Portraits without People: Leonard Kleinrock. In this digital composition from the Portrait Unbound series, Weingarten alludes to interests, achievements or moments within the subject’s life without picturing the person — in this case, UCLA Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Computer Science and internet pioneer Kleinrock.

Displayed in Marion Anderson Hall is a large-scale mixed media collage on rice paper and canvas from circa 1975 by an unknown artist, given by Pam Schulz (’83) and Clark Dikeman (B.A. ’72) from the estate of Dikeman’s mother June. Along with the modern and contemporary pieces are a few from other periods in various media, such as a set of 19th-century architectural drawings on silk. These were given by the family of Xavier Dreze to honor the late marketing professor for whom Anderson named an annual prize for outstanding research by a Ph.D. student.

An Acquired Taste

Some artists are represented in Anderson’s collection in part because their work struck a harmonious chord with Morrison’s sensibilities. Mona Khan, the sister in law of Professor Emeritus Dominique “Mike” Hanssens, who was the Morrison Center’s first faculty director, is a Barcelona-based artist who was commissioned to paint Olympians’ official portraits for the 1992 summer games. “She wanted to give us Sea View at a time when she’d told Mike her gallery was bugging her to make more paintings because they kept selling out,” says Morrison. “I’ve never met her but I corresponded with her. She was so pleased we accepted her piece that she wrote a hand-written thank you note saying if Sherie and I were ever in Barcelona, we should stay with them. What a nice person!” Khan’s luminous gift can be enjoyed in Gold Hall.

Morrison is also particularly fond of intricate abstract paintings by Don Sorenson, whose career was cut short when he died of AIDS at age 37, early in the epidemic in 1985. One was donated by the Knapps and the other by Halle and Cary (J.D. ’72) Lerman. Morrison likes Something Like Red Bell Peppers by painter Gus Harper, who happened to be a jogging buddy of a former Anderson building services staffer. Thanks to that accidental connection, in addition to two of Harper’s O’Keeffe-like canvases, the school enjoys the loan of an acrylic-on-wood triptych by Harper’s mother, too.

Morrison, the humble unofficial curator of Anderson’s art collection, must be selective because of space limitations and the school’s ability to preserve and maintain fine art in perpetuity. When donor Anita Green called him to offer one of the heavier sculptural pieces by Laddie John Dill, Morrison demurred on the basis that it would cost too much to install. Green was so persuaded the work should enter the collection that she blithely arranged for Dill’s crew to install it at her expense.

Morrison recently declared that his friend Dill is creating a five-by-five-foot Square of Pythagoras for Anderson that pays homage to the Pythagorean tilted square-within-a-square theme in the buildings’ floor pattern. “He’s been working on it for years, but he gets so busy. We have a space for it,” says Morrison, who plans to hold Dill to his promise of the gift.

Morrison has lately offered UCLA Anderson staff and faculty guided tours of the collection to better acquaint the community with what they’re seeing every day as they rush — as he once did at MIT — from place to place on campus. Clearly, his reputation as curator has preceded him because he still regularly fields unexpected inquiries from potential donors in the arts, entertainment and business. Though he cautions that it’s not an active acquisition program, who but Don Morrison could possibly be more “official” in this capacity?