"This Is Not Working"

“This Is Not Working”

It’s because recently [the media] noticed that the supply chains are broken. [There was] the panic-buy for consumer goods such as masks, hand sanitizers, vitamins and toilet paper. That’s why the public has become more aware, because of the shortage. People started questioning why there is a shortage of face masks? Ventilators?

As for the toilet paper, that one is actually not true. A lot of consumers are not aware of the fact that toilet paper is made in the U.S. There is a constant supply, most of it is manufactured in Pennsylvania, with the paper pulp mills located in North Carolina and other states. The United States has the entire supply chain for toilet paper under control. That’s not the problem.

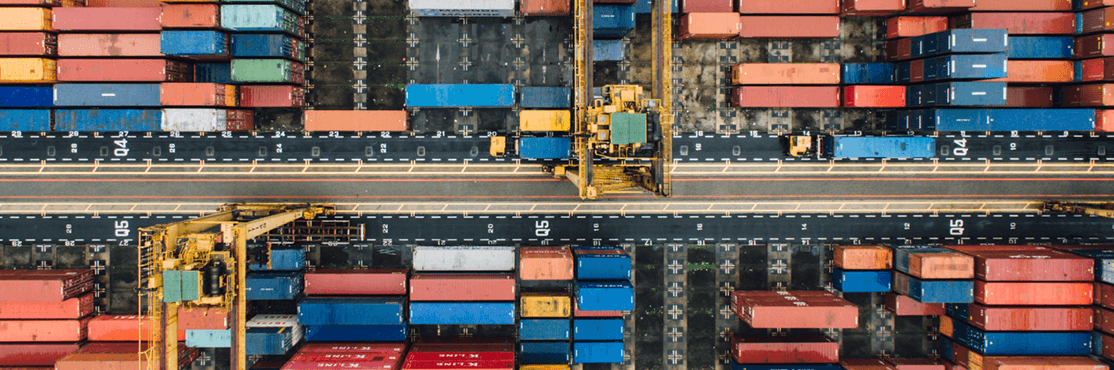

For other products, we’re in a major crisis. It’s partly because the supply chain is global and because we have bought into the idea of a frictionless, free-trade-agreement global supply chain, and let different countries to do what they do best. That was the idea, but this is not working. The supply chain is broken. And then you have the kind of global crisis that we have not seen for the last 100 years. Therefore, it is a wake-up call on how to deal with the broken global supply chain for these kinds of products.

What can we learn from it, how can we move forward? Right now, China has to restore part of the production for the face masks, gloves and other products. They are shipping but there are delays because many countries banned all traffic from China. A lot of medical supplies were stuck at the port. I think that now we have commercial aircraft to transport tons of the medical supplies from China to the United States. I think that’s alive today. But there was a delay.

UCLA Distinguished Professor Christopher S. Tang

Before we get to lessons learned for the future, let’s talk about the current crisis.

Right now, the federal government is asking Ford and GM to build ventilators and Hanes to produce face masks. The request is clear, but the response is much more complicated.

First of all, Hanes may not be able to produce N95 face masks because they require specific fibers to ensure a high degree of filtration efficiency and a certain manufacturing process. It’s not just a matter of converting underwear material to make the masks; it doesn’t work like that. You need the filtering system. And those filters, they’re made in China. A lot of hospitals are asking people with sewing machines to help make masks, but those are just the basic materials. They’re better than nothing, but you cannot really filter out the virus. That’s problem number one.

Problem number two is that [the government] is asking Ford and GM to produce ventilators. These kinds of manufacturers cannot flip the switch from producing cars to producing ventilators because it requires a different supply chain in terms of components, in terms of the know-how, in terms of the equipment, in terms of the manufacturing process, in terms of the regulations and compliance to meet certain medical standards. Therefore, it would take a long time for Ford [or] GM to produce ventilators in the U.S. because you need components, equipment; you need the people to assemble the product and to meet the standards for medical equipment. The safety standards for medical equipment as they relate to car manufacturing safety standards — they’re entirely different topics. It’s not easy, it would take some time.

So, what if we survive this crisis? What would be the short-term and long-term impacts on the global supply chain? I think the idea of a frictionless and connected global supply chain … is a farce. It’s not reality. Then the question is, what to do next? I think it depends on different companies and mindsets. Because the United States is a free market economy, it’s very difficult to have a coordinated plan. In this case, I hope the federal government, and maybe state governments, will work with the private sector to come up with a coordinated plan. If you leave them to their own devices, companies will continue to source from other countries because it’s easier, faster and cheaper, right?

If you want companies to change the way they manage the supply chain, the government needs to have some form of intervention or incentives, in particular, for critical products that could affect people’s lives. Clothing items are not so critical, so they can go through the supply chain elsewhere, it’s fine.

But for personal protective equipment (PPE), medical equipment, for humanitarian types of products, I think the United States needs to keep some form of capability to produce locally. The reason I push for this (I’ve said this for decades but no one listens), a nation cannot afford to have everything critical made by other countries, especially when there is a world crisis. Each country needs to protect its own citizens, they need to fulfill the demand for their own country first. This is exactly what is happening now: in the race to secure medical supplies, many countries ban or restrict exports.

Therefore, for critical products, I think the government needs to work with private enterprises to ensure that there is at least adequate — or at least some basic minimum — capability to produce such products within the country. It may be a little more expensive, but if a company can produce a little bit in house, automatically, and also source globally, they can use the internal ability as a benchmark to compare cost, quality and delivery.

During normal times, at least we can use it as [leverage] to ensure that overseas suppliers would do the right thing, and do it well and cheap and fast. When you’re facing a crisis, at least the internal domestic operations can ramp up because you maintain some form of capability. Right now, there’s no hope to ramp up quickly. I have been lobbying for this dual-prong approach for a long time, and Brooks Brothers did exactly that. By using its domestic factories, Brooks Brothers is now making basic masks (probably not N95 masks) and gowns for medical professionals.

All this means that we need to have a domestic supply chain, with the global supply chain running in parallel. If one of them is broken, at least you have a backup supply chain that can run domestically.

The other element I like to raise is stockpiling.

I think there are certain things that we must stockpile in the United States, especially for humanitarian relief products. Otherwise, it is too risky. I think if the federal or the state governments can work with the local enterprises to maintain some stockpile of critical products, as well as production capability, that would create jobs and also maintain some capability internally. That would create opportunities for innovative products that we can make in the United States.

If we can, if we think about the global supply chains more strategically, I think that something good could come out of this crisis.