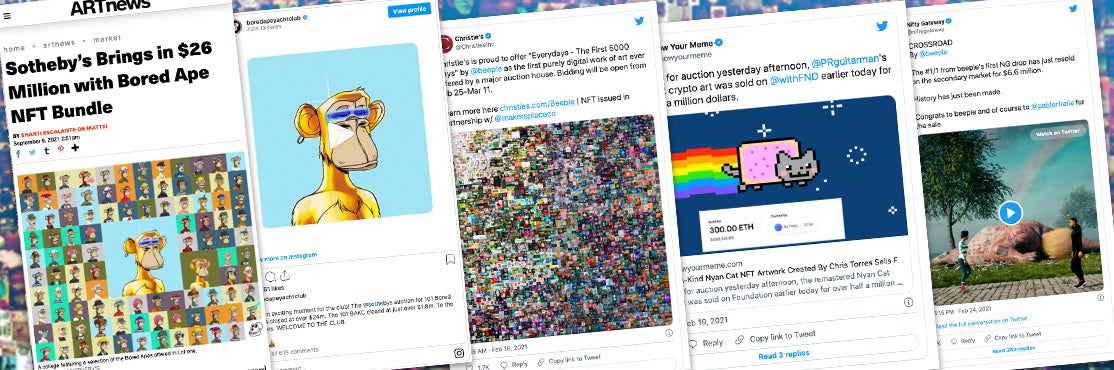

Twenty twenty-one was the year nonfungible tokens (you’re likelier to know them as NFTs) exploded within the public consciousness. In March 2021, a digital piece created by the artist Beeple sold for $69.3 million in a Christie’s online auction. A-list celebrities jumped in — some as investors, others as creators, still others as digital-collectible hobbyists participating in online marketplaces such as Bored Ape Yacht Club, where NFT-based avatars start at prices north of $200,000. DappRadar, which tracks transactions on the blockchain (if you don’t know what that is, we’ll get there), estimated that NFT sales generated $23 billion in 2021 — a meteoric rise from 2020, when they garnered $100 million. In November, Collins English Dictionary named NFT its word of the year, citing an 11,000% increase in usage over 2020.

Yet for all of the buzz, wide swaths of the population inhabiting the physical world either have no clue what an NFT is, or possess only a cursory understanding based on the headline-grabbing transactions; just enough, in other words, to wonder why anyone would pay staggering sums for ownership of digital files that anyone can access.

Three UCLA Anderson alumni who have become heavily involved with NFTs through their business and consulting work say there’s much more to the story than what can be gleaned from the headlines.

In the simplest terms, an NFT is a certificate of ownership and authenticity of an asset, usually digital (though it can be physical). It is recorded on the same decentralized blockchain technology used as a transaction ledger for cryptocurrencies, where it can be bought, sold or traded. Unlike cryptocurrency, which is interchangeable (i.e., fungible), each NFT is unique. That uniqueness, along with the ability to verify authenticity and ownership, is where it derives its value.

Rikin Mantri (’13)

The digital assets under the NFT umbrella go well beyond works of art, and you don’t have to be wealthy to get them. In November, for example, Warner Bros. dropped 100,000 NFT avatars inspired by The Matrix film franchise, priced at $50 each. In some cases, buyers might view these and other NFTs as investments, but more often their appeal is non-monetary. It’s a rapidly evolving space that’s certain to look quite different in the not-so-distant future, but the Anderson alumni, all three of whom have closely followed the evolution of NFTs over the last five years, are confident they’re here to stay, with transformative implications. “We’re in the first inning of a very long game,” says Rikin Mantri (’13), co-founder and co-CEO of Curio Digital, which works with entertainment industry clients to engage fans through NFT-fueled digital collectibles.

Mantri, a former entertainment and digital executive at William Morris and Disney, and fellow Anderson graduate and co-founder Ben Arnon (’07), a media and tech entrepreneur, began talking several years ago about business ideas around the convergence of entertainment and technology — in particular, tokenizing intellectual property. They established Curio and launched their first NFTs into the market in February 2021, at the dawn of the revolution. Today, they bill Curio as “the premier NFT platform for the biggest names in entertainment,” working across film, TV, music, graphic novels and gaming.

“In digital media, items like JPEGs and audio files previously had no perceived value because they were so easy to copy and share,” Arnon says. Now, he explains, beyond the utility or enjoyment one can get from the digital asset, it can carry monetary value based on supply and demand. Yes, you can view a replica of the Mona Lisa, but only the Louvre in Paris has the original. “If you buy a pair of Jordan 13 sneakers at the store as a collector, it’s because you have an emotional resonance to it and think it’s going to rise in value,” Mantri says. “With NFTs, value is assigned to a digital asset because it’s on the blockchain and only a fixed number have been created. That value is then determined by what people are willing to pay.”

Ben Arnon (’07)

While NFT-based art attracted the most coverage in 2021, significant activity was occurring in other areas. Dapper Labs’ NBA Top Shot allows fans to buy, sell and trade officially licensed NBA and WNBA video highlights as collectible NFTs, some for as little as a few dollars. Generative avatar projects such as Bored Ape Yacht Club and Larva Labs’ CryptoPunks — 10,000 unique, algorithmically generated, pixelated characters, credited with igniting the NFT craze in 2017 — have led a growing digital collectible market. In gaming, the play to earn model rewards participants with NFTs based on certain actions. NFTs are also serving as access tokens to unlock exclusive fan experiences, both online and offline, including in the virtual spaces increasingly known as the metaverse.

Curio is interested in the evolution of NFTs as storytelling vehicles. “We’re starting to see them as the next incubator of IP,” Arnon says. “Just as Hollywood has been making movies and TV series based on comic books and podcasts, in the future, NFTs will serve as the underlying source material, creating characters and story lines.”

As a digital consultant to brands and creators, Lea Kozin (’10) sees NFTs as a way to help clients deliver value to customers, users and fans. Kozin owns Ixsight, a digital-marketing strategy consultancy with a focus in tech, media, sports and consumer packaged goods. “I’ve been really encouraged to see more of my clients take an interest in NFTs and am looking forward to integrating them more into my work, especially as the metaverse explodes over the next three years,” Kozin says.

Lea Kozin (’10)

When it comes to NFTs as investments, Kozin urges caution, noting their volatility. “Most investors who are doing well with NFTs are committing a significant amount of time,” she notes. “That’s not to say the average investor should stay away. So long as you have time, curiosity and faith in the tech, invest your time in learning, and jump in only after you cross your personal conviction threshold. Gain a comprehensive understanding: first about blockchain technology, smart contracts and NFTs in general, then about the specific NFT projects you’re considering backing.”

Kozin points out that any speculation about future winners and losers in the NFT space must come with a strong disclaimer — it’s early. While interesting, she says the NFT art collections that have been snapped up for astronomical sums should be seen as outliers. “Although it’s plausible for some of these early NFTs to have viable secondary markets in the future, I believe the ‘winners’ will be the NFTs that have utility beyond just existing in the digital world — NFTs that unlock other capabilities, drive network effects and facilitate movement across the metaverse, as well as those that verify ownership of real-world assets, for example,” Kozin says.

Arnon suggests that viewing NFTs solely for their potential appreciation in value might be the wrong approach. “We already see blue chip NFTs that will have value for some time, but probably 90-plus percent will significantly drop, some to zero,” he says. “Unless people are really studied in blockchain and NFTs, they should be purchasing them because they love the art or the TV series they’re based on, or for the utility they’re going to provide.”

NFTs could dramatically change the relationships between content creators and consumers, Mantri notes. For example, the “smart contracts” that govern NFTs could stipulate that the artist gets a share of the revenues each time an NFT is sold. “You have the ability to track not only the first transaction, but subsequent transactions,” Mantri says. “We’re at the very cusp of understanding what this notion of a creator economy means.” He notes that the emergence of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), controlled by members based on rules and transactions maintained on the blockchain, has set the stage for a new model of financing and distributing content as NFTs. “What it means to be part of that as an audience member is also going to shift,” Mantri says. “At Curio, we’re excited to build out a platform that can make money while getting fans closer to the content they love and make their NFTs more valuable.”

Kozin suspects that as the frenzy over the exorbitant prices paid for art NFTs and the celebrity-endorsed drops wanes, the next phase will be characterized by a growth in niche-specific NFTs as well as utilitarian applications of the technology. “People with an interest in gaming will use and proliferate gaming NFTs; people in real estate will use and proliferate real estate NFTs; musicians, music NFTs; and so on,” she says. “And across verticals, there are utilitarian applications that will become more widely adopted, such as identity verification, certification, recordkeeping, digital signatures and supply chain/logistics tracking.”

The Curio co-founders share Kozin’s vision of NFTs’ expansive role. “That acronym is going to be ubiquitous with a lot of the things we do in our daily interactions in both the physical and digital worlds,” Mantri predicts. Adds Arnon: “Some of the ways we’ll see NFTs utilized in the next 6 to 12 months aren’t even on our radar now.”

Arnon enrolled in the Anderson MBA program in 2005 after spending three years working in music and film at Universal Pictures. For someone looking to move from traditional entertainment into digital media, his timing was fortuitous: By the time he graduated, the transition to the participatory Web 2.0 was going full bore, buoyed by the exploding popularity of YouTube, Facebook and the first-generation iPhone. “There was a huge shift underway, and Anderson opened up a new world for me,” Arnon says. As Curio participates in the next iteration of the internet — so-called Web 3.0, focused on decentralization — he says: “There are many areas outside my expertise, but if I’m in the room, there’s nothing I haven’t been exposed to, thanks to my Anderson education. That gives me confidence in any business situation.”