January 2023

January 2023

The Journey of Humanity

Leo Feler, Senior Economist, UCLA Anderson Forecast

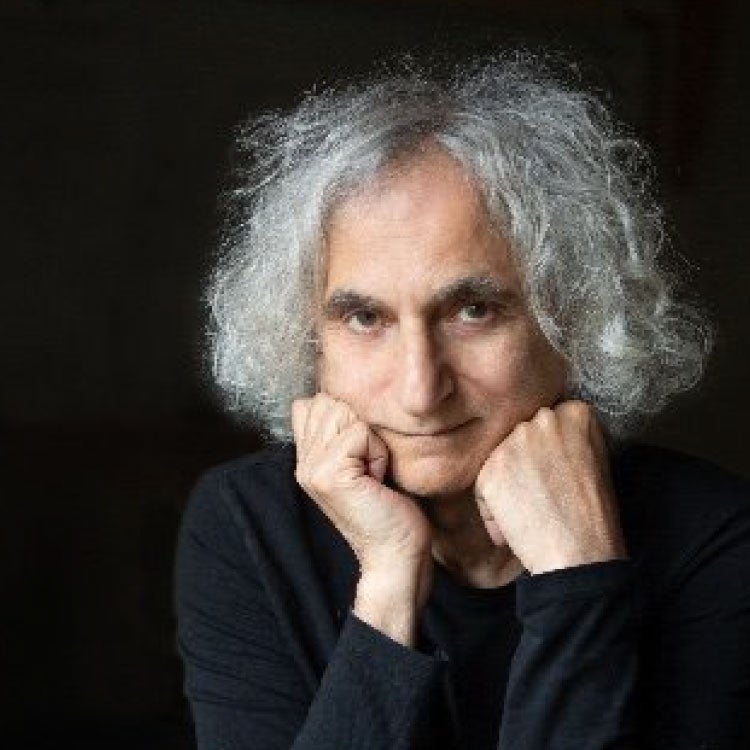

Oded Galor, Professor of Economics, Brown University

January 2023 Economic Update

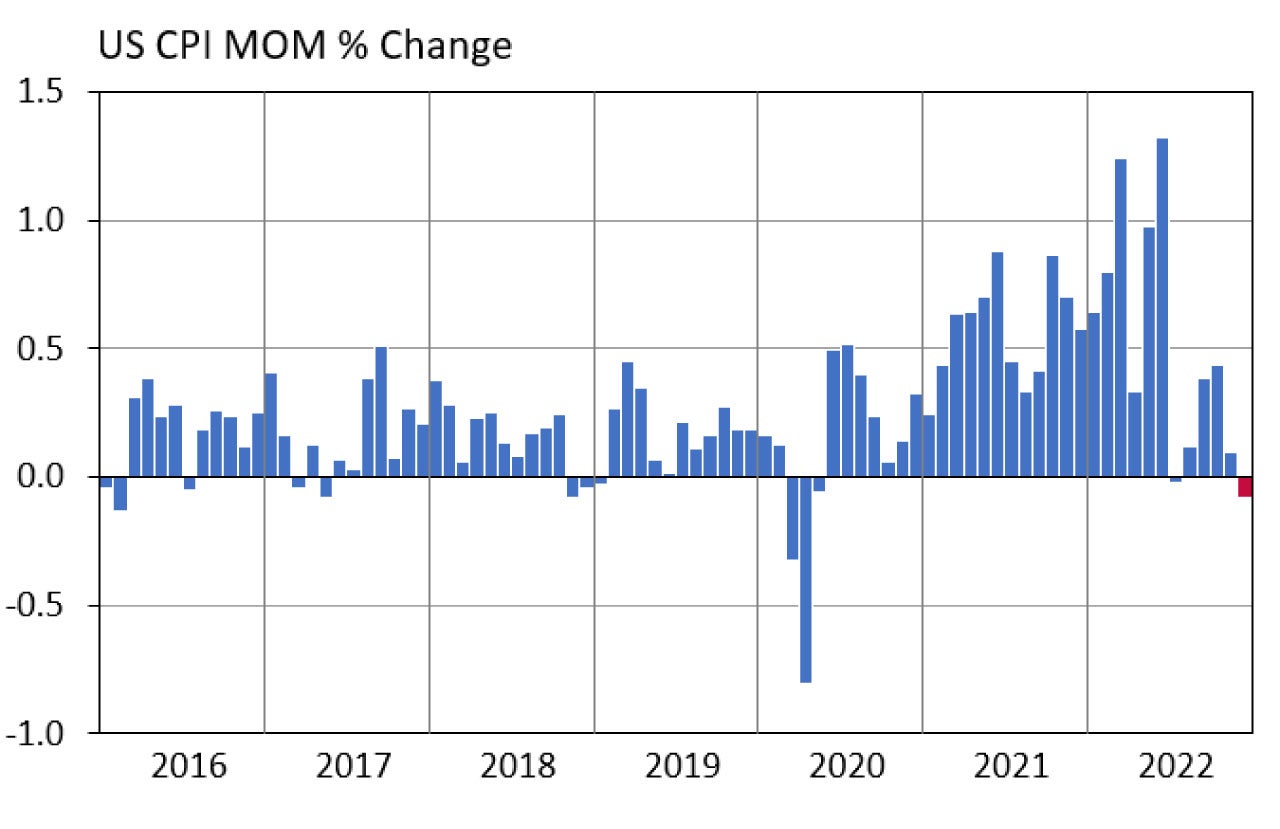

- The December CPI came in at -0.1% MOM.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics. - Leading the declines were energy and goods. Food inflation moderated, but services inflation remained high.

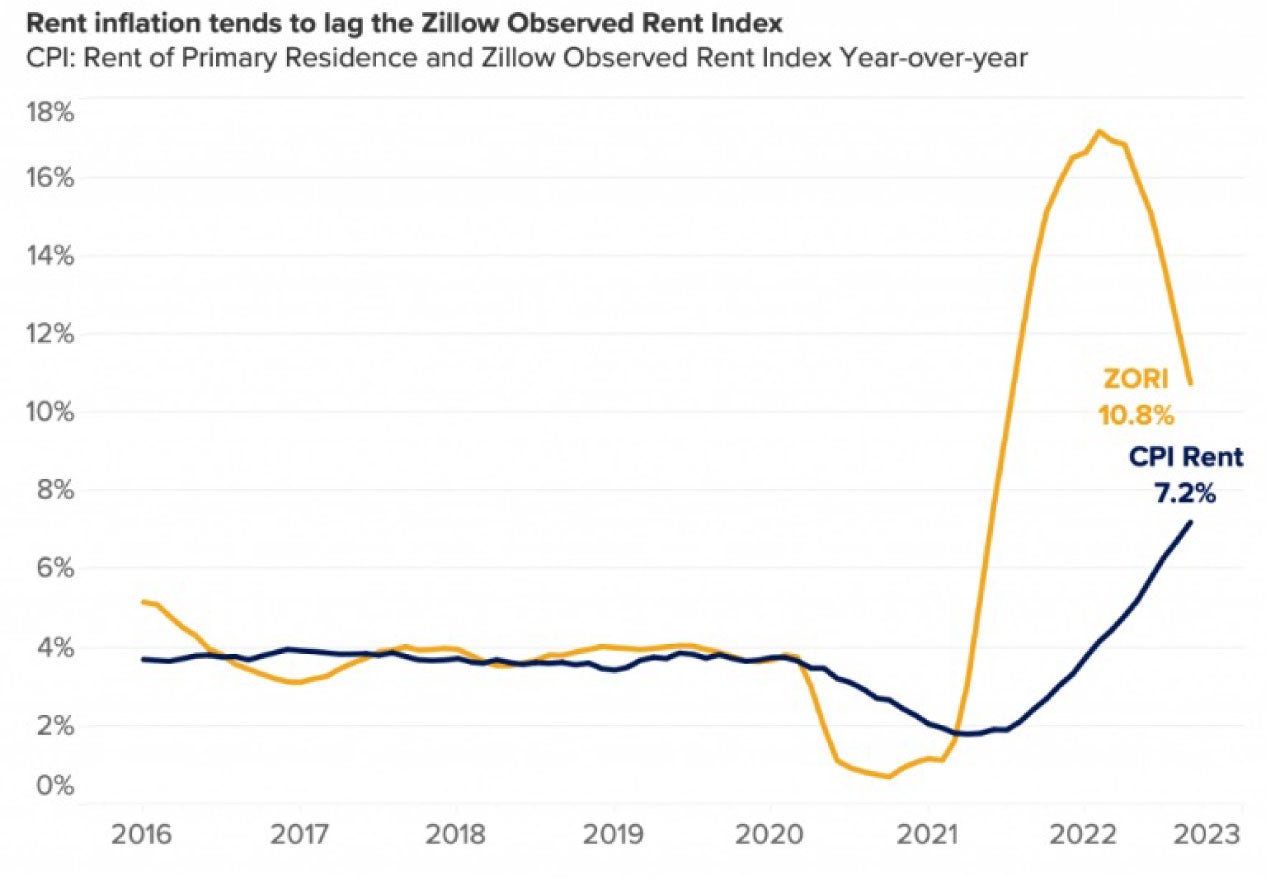

- Services inflation remained high in part because of shelter inflation, but data from Zillow indicate that rents are declining, which should help ease shelter inflation later in 2023.

Source: Source: Zillow, available at: https://www.zillow.com/research/rent-inflation-31602/

Source: Source: Zillow, available at: https://www.zillow.com/research/rent-inflation-31602/

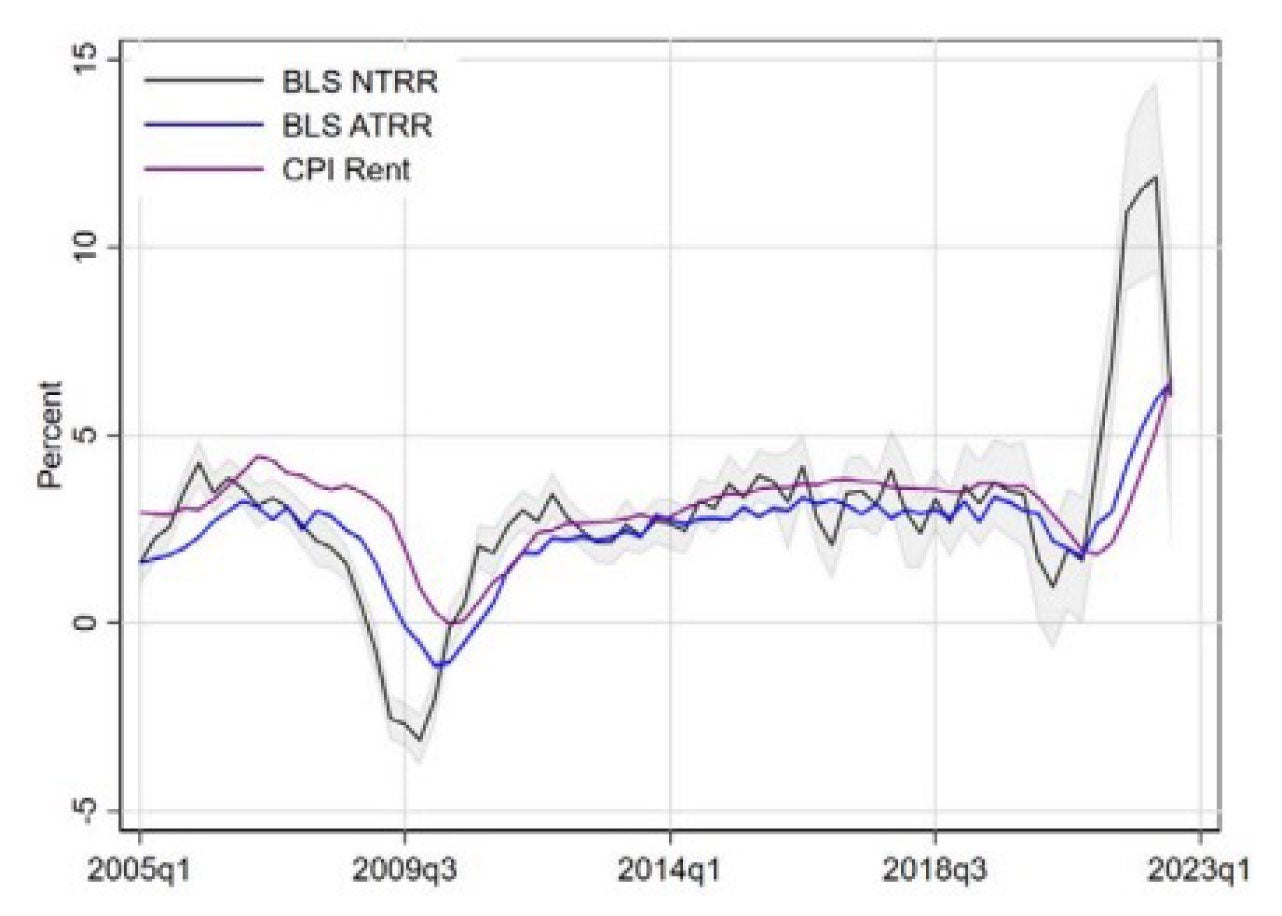

- Similarly, a new Cleveland Fed measure of rents suggests that shelter inflation will likely begin declining in 2023.

Notes: NTRR = New Tenant Repeat Rent Index; ATRR = All Tenant Repeat Rent Index; CPI Rent = Rent of Primary Residence. Source: Adams, Brian, Lara P. Loewenstein, Hugh Montag, and Randal J. Verbrugge. 2022. "Disentangling Rent Index Differences: Data, Methods, and Scope." Working Paper No. 22-38. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-wp-202238.

Notes: NTRR = New Tenant Repeat Rent Index; ATRR = All Tenant Repeat Rent Index; CPI Rent = Rent of Primary Residence. Source: Adams, Brian, Lara P. Loewenstein, Hugh Montag, and Randal J. Verbrugge. 2022. "Disentangling Rent Index Differences: Data, Methods, and Scope." Working Paper No. 22-38. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-wp-202238.

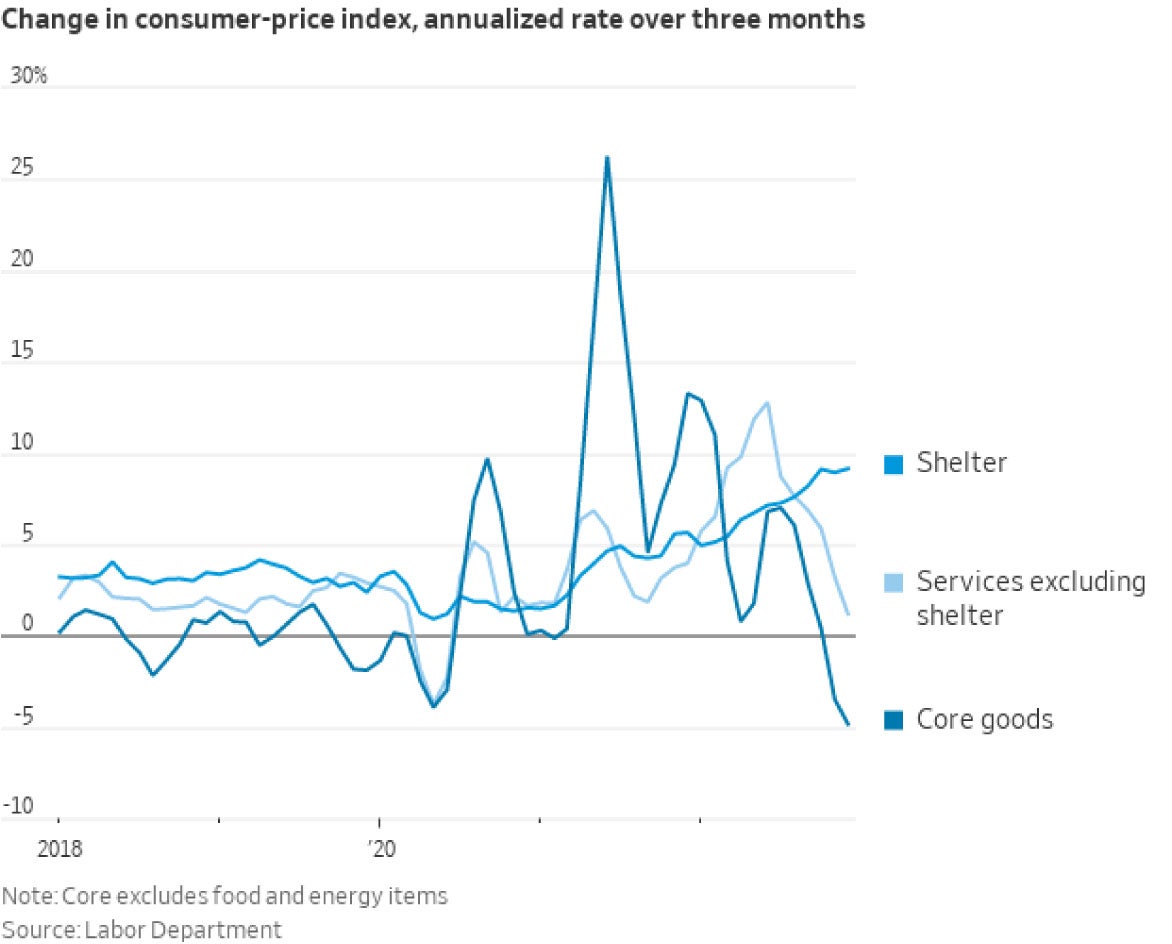

- Over the past 3 months, excluding shelter inflation, core goods and services inflation have declined.

Source: Nick Timiraos, The Wall Street Journal, Jan 12, 2023, available at: https://twitter.com/NickTimiraos/status/1613535547125018625

Source: Nick Timiraos, The Wall Street Journal, Jan 12, 2023, available at: https://twitter.com/NickTimiraos/status/1613535547125018625

. - Collectively, these data suggest the Fed may be close to pausing its interest rate hikes. However, since monetary policy works with “long and variable lags,” it is unclear at this time whether the economy may continue to slow and tip into recession in 2023, or whether the Fed will have succeeded bringing down inflation without causing a recession.

A Conversation with Leo Feler and Oded Galor

This month, we feature a conversation with Oded Galor about his book, The Journey of Humanity. Oded Galor is the founder of unified growth theory. His book describes the history of human evolution, from stagnation to growth, and the origins of inequality.

Leo Feler: I'm very honored to have with me today Oded Galor, Professor at Brown University. Oded developed Unified Growth Theory and wrote a magisterial book, The Journey of Humanity, summarizing his research and the research in the field about the history of human evolution and the state of our world as it exists today. Oded, thanks so much for joining us.

Oded Galor: It is my great pleasure to be on your show.

Leo Feler: The title of your book is fitting, The Journey of Humanity. You take us on this amazing journey from the cradle of humankind all the way to the present. You help us better understand ourselves in our world. I guess we should start from the very beginning, which is the beginning of humanity and what life was like in that era. Can you tell us about how humanity begins and what life is like in the first stages of human existence?

Oded Galor: Humanity emerges in Africa nearly 300,000 years ago. At the time, humans are preoccupied by survival and reproduction, living standards are very close to the subsistence level, and there are minor differences in living conditions across time and across space.

Nevertheless, unlike other species, humans are equipped with the human brain. And consequently, humans are engaged in a process of innovation, very rudimentary at a time, but nevertheless, innovations that can alter the environment in which people operate. Perhaps most importantly, these innovations help to gradually expand the human population.

Despite this process of innovations, and despite this process of the expansion of the size of the human population, what we see over this time period is that the standard of living is stagnant.

Leo Feler: Why do so many thousands of years pass with no major improvements in living conditions, and I think you mentioned in your book there's a decline in living conditions which leads to this concept of a lost Eden. What's the reason for that?

Oded Galor: We consider human history in the context of Homo Sapiens during the past 300,000 years. It is quite striking that over 99.9% of human existence, humanity is in what one may define as a Malthusian trap in the sense that living standards are hardly changing over most of human existence. In contrast to some conventional wisdom, we do not see a gradual improvement in living conditions in the course of human history. We see, in fact, a long process of stagnation in the context of living standards, and then a tremendous metamorphosis just in the past 200 years.

Now, if you think about the past 200 years, unlike what existed earlier, in which, say, life expectancy fluctuated in a very narrow range of 25 to 40 years, we see that living conditions, as reflected by life expectancy, has more than doubled in the past 200 years. Or, if we consider income per capita, it is quite striking that income per capita, as I said earlier, is fluctuating in a very narrow range around subsistence level for 300,000 years, and then, quite strikingly in the past 200 years, we see this incredible fourteen-fold increase in the standard of living in the world as a whole.

What trapped humanity over 99.9% of human existence? This was a time period in which earlier technological innovations took place. They were not at the pace that we see today. It was one stone tool that was replacing another stone tool, very rudimentary technologies, but nevertheless, this technological progress permitted an expansion of resources.

This expansion of resources was not long lasting. It permitted more children to survive. It permitted more children to be born, and ultimately these resources were divided over an increasing number of people. Consequently, resource per person did not change over 99.9% of human existence. And this is what we define today as the Malthusian trap, the counter-balancing effect of population growth on technological progress. Technological progress and population are increasing proportionately, and as a result, we do not see changes in living standards.

Leo Feler: There seems to be a catalyst that leads to economic takeoff, and we suddenly escape the Malthusian trap. But was it really a catalyst? Or was it this gradual building up of density, of population, of technology that somehow led the welfare of human beings to take off?

Oded Galor: Indeed, so over most of human existence, we don't see changes in living standards, but nevertheless we do see a certain dynamism that occurs in the context of the size of the human population, the rate of technological progress, and the degree of adaptation of the human population to the technological environment. The Malthusian epoch is characterized by an important dualism.

On the one hand, stagnation in living standards as reflected by life expectancy and income per capita. But, on the other hand, there is great dynamism in the context of technology, in the context of population, and in the context of human adaptation. So, when humanity emerges in Africa 300,000 years ago, the size of the human population is modest. But these humans are able to innovate, and consequently this innovation leads into greater population. With a greater number of potential innovators, innovation becomes faster, supporting more people. This reinforcing interaction between what I define as the wheels of change – technology, population, and human adaptation – is being reinforced in the process of development up to a point in which we move from strong tool technologies that existed 300,000 years ago to steam engine technologies and industrialization.

The technological environment starts to change very rapidly. This rapid change in the technological environment necessitates education and human capital to permit people to cope with the rapidly changing environment. Education is not free. People are very poor. They cannot economize on consumption in order to afford educating their children. Instead, they have to economize on the number of children they have in order to be able to afford educating them. Unlike what existed over 99.9% of human existence, the counterbalancing effect of population on technological progress is no longer present. Consequently, technological progress is converted into more prosperous people rather than into more people.

Leo Feler: Do you see climate change and environmental degradation as potentially posing a new kind of Malthusian trap?

Oded Galor: Certainly, the potential is there. And when we think about climate change and environmental degradation, it appears, perhaps, as one of the greatest challenges that humanity has faced since we emerged 300,000 years ago. Now, we faced great challenges before, and human ingenuity was able to rescue us from each of these challenges. While the particular challenge of climate change appears quite demanding, I do not think we will see ourselves reverting to a Malthusian trap. The reasons are the following. What kept us in the Malthusian trap is the counterbalancing effect of population on technological progress. The world has reached a new state, in which, we see a gradual decline in fertility in most places around the globe, well below replacement level, and consequently, the counterbalancing effect of population on technological progress is no longer present. This is very important in the context of climate change as well because we are polluting the Earth, but the current trend of declining population growth is, in fact, mitigating the adverse effect of the human population on the environment.

Second, during the transition from stagnation to growth, we see an incredible increase in the level of education of the human population. This is very important for two reasons. The first is that a more educated population can comprehend the adverse effects of our actions on the environment, and as a result, take responsibility and try to reverse the current course of climate change. And perhaps more importantly, human ingenuity has reached such a critical stage, where, with proper incentives and with proper behavior on the part of humanity as a whole, human ingenuity can rescue humanity in the coming decades from the potential adverse consequences of climate change. Again, climate change is an enormous challenge that cannot be underestimated. But nevertheless, if we do take the appropriate actions, if we act responsibly, then we do have the ability to overcome this potential catastrophe.

Leo Feler: While you don’t seem to think we’ll experience a decline in our living conditions because of climate change or environmental degradation, do you think this epoch we’ve experienced of very rapid growth is likely to be short lived? For example, economists like Robert Gordon at Northwestern University mention that we've already experienced a boom in growth during the demographic transition, and that maybe the best years of growth are behind us. What do you think about our prospects for having continued rapid growth versus just maintaining the current standard of living that we have right now?

Oded Galor: If we take a very broad view, and this is the view that I take in my book, The Journey of Humanity, it is quite apparent that technological progress has increased gradually in the course of human history, but not necessarily monotonically. There are different growth paradigms. The observations that Robert Gordon makes are valid to a large extent in the context of the discussion that he conducts in his book, but I do not think they are sufficiently forward looking. And I do think that within a given technological paradigm, we may see a decline in the pace of technological progress. But, from time to time, we see paradigm shifts, and once the paradigm shift is happening, we see an explosion of technological progress that takes us into a new state of development. So my prediction is that we will see further technological progress in the future, and perhaps even at a much faster pace than we see today. I think we will see paradigm shifts that will permit humanity to expand into territories that we cannot even envision today. And this is the nature of technology. This is how technologies were perceived in the past as well. Any time that humanity experienced a major technological breakthrough, this technological breakthrough could not have been envisioned three or four decades earlier, and the same will be true going forward. So, in fact, I do not share the pessimism of Robert Gordon and others. I think humanity will maintain its relentless march forward.

Leo Feler: This is a good opportunity for us to shift to the second part of your book, which is on inequality. Before the Industrial Revolution, is it fair to say that living standards across the world were relatively equal, but equally poor? And then why did some parts of the world experience the Industrial Revolution sooner? This is a broad question, and perhaps we can break it into a few parts. What roles did institutions, culture, and geography play in allowing economic takeoff to occur sooner in some areas of the world and not others? What do you think will happen to inequality moving forward?

Oded Galor: My book, The Journey of Humanity, addresses two fundamental mysteries. What I defined as the mystery of growth, namely, the transition from stagnation to growth that occurred in the past 200 years, and the mystery of inequality, namely the emergence of vast inequality in living standards across the globe in the past 200 years.

As I argue in the book, the two mysteries are intimately linked. It is the transition from stagnation to growth and the dramatic metamorphosis in living standards that occurred in the past 200 years that led to much of the inequality we see in the world today. If you observed the world at the beginning of the nineteenth century, income per capita in the most advanced nations in the world compared to the least developed nations was at a magnitude of about 3 to 1. When we think about income per capita today, it is about 15 to 1, 20 to 1, or 100 to 1 depending on how we define regions of the world. Much of the inequality we see across the globe today originated in the past 200 years. It originated due to the differential transition from stagnation to growth across the globe. Some societies, Western Europe and their offshoots in North America, took off at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Other societies took off only recently. And since this takeoff was associated with a fourteen-fold increase in the standard of living in the world as a whole, an incredible inequality emerged in the world economy.

The question, of course, is why is it the case that 200 years ago, some societies were able to take off earlier than others? In the second part of the book, I try to decipher the roots of this inequality, and I go through different phases. Initially, I focus on the role of colonialism, extraction, and asymmetric trade in expediting the transition of developed societies from stagnation to growth and delaying the transition of developing societies from stagnation to growth. Then I discuss the role of institutions, namely the emergence of growth enhancing institutions in some societies and the emergence of extractive and growth-retarding institutions in others across the globe, and I cite examples in which these differential institutions are critical for the understanding of economic development. But I argue that institutional characteristics, political institutions and economic institutions, to a large extent are a by-product of the process of development as a whole. They emerge in order to facilitate interaction across individuals and to foster economic development once society started to be formed. This leads us into deeper forces that are behind institutional characteristics. Similarly, in the context of culture, we see the emergence of growth-enhancing cultural traits in some regions of the world and the emergence of growth-retarding cultural traits in other regions of the world. But again, cultural traits are a by-product of the environment in which these cultural traits emerged. As a result, I revert back to the role of what I call geographical characteristics and societal characteristics in forming institutional and cultural characteristics and uneven development. I conclude that to a large extent, it is the geographical heritage of societies and its impact on the emergence of culture and institutions, and it is human diversity, and its impact on innovativeness and the degree of social cohesiveness, that is behind the inequality we see across the globe today.

Leo Feler: Can you talk about the role that human diversity has in facilitating economic growth or perhaps holding back economic growth?

Oded Galor: When we think about diversity, it has conflicting effects on economic development. On the one hand, diversity is associated with cross-fertilization of ideas, and this is conducive for innovation and economic development. On the other hand, diversity is associated with social non-cohesiveness. It is associated with mistrust. It is associated with disagreement about the desirable level of public goods. And it is associated with social conflicts. This implies there is a sweet-spot level of diversity that balances between the beneficial effects of diversity in increasing innovation and the detrimental effects related to social cohesiveness. Interestingly enough, when we view human history, it appears that the beneficial effects in the Middle Ages and before were associated with societies like China, Korea, and Japan, societies that we do not perceive today as perhaps being optimally diverse. These societies at the time, given that the pace of innovation was not very rapid, managed to balance the two effects in an optimal way, namely, social cohesiveness was so important that these relatively homogeneous societies had the upper hand in the context of diversity. But as we move into the present day, in which technological innovations are much more rapid, the optimal level of diversity is associated with societies like the United States, namely, societies that are much more diverse than the societies of Southeast Asia. This diversity is very beneficial in generating the cultural fluidity that permits society to cope with rapid technological change despite some disadvantages in the context of social cohesiveness. And this implies that as we move further into the future, and we move into a more and more demanding technological environment, in fact, diversity will be key for human prosperity because diversity will generate the cultural fluidity that is needed to cope with the rapidly changing technological environment.

Leo Feler: What do you think the next steps are in the journey of humanity?

Oded Galor: My prediction is that the rate of technological progress will continue to accelerate. As a result, it will require greater ability of humans to adapt to the rapidly changing technological environment. What we saw in the past two centuries is a greater emphasis on education as a tool that allows individuals to adapt better to rapid technological progress. Part of the development that I predict will occur in the coming decades will be that technology will enhance the cognitive abilities of humans and will allow them to adapt to the incredibly rapid changes in the environment.

At the same time, I suppose the inequality we see in the world today, and the rapid increase in the inequality we have seen within countries in the past four or five decades, will maintain its course, at least for the next few decades, in the sense that technology will be more demanding in the context of education and cognitive abilities, and since these traits are relatively scarce, we will see a gradual increase in inequality beyond what we see at a moment. This implies that responsible societies would have to invest more in assuring equality of opportunities and that each individual will have a fair chance to participate in this technological lottery. At the same time, society should be prepared to develop safety nets for those individuals that at the moment do not have the matching skills for the new technological environment. Hopefully, down the road, technological progress will enhance cognitive skills across society as a whole, and as a result, perhaps that will operate towards the mitigation of inequality.

Leo Feler: Oded, thank you so much for joining us and for talking about your book. It’s a fantastic read, and we really appreciate you taking the time to have this conversation with us.