UCLA Anderson Forecast

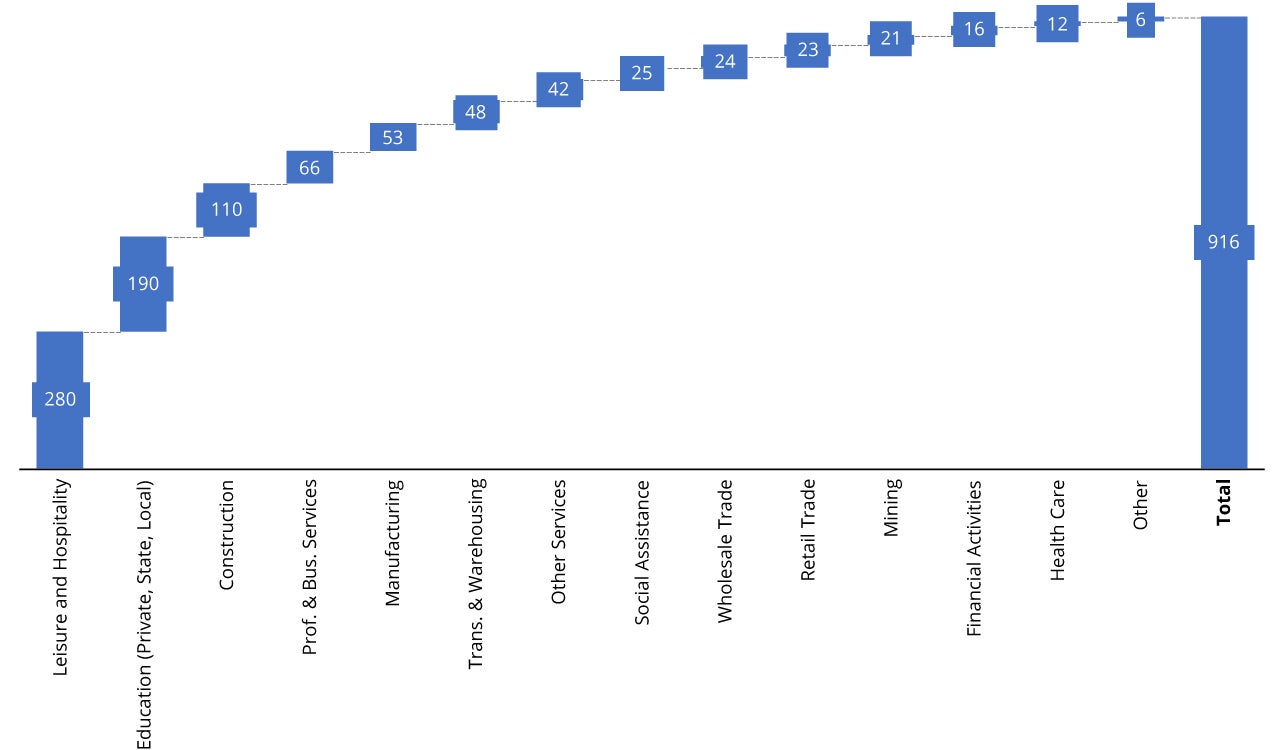

Figure 1. March Job Gains: Change in Employment, In Thousands, Feb 2021-Mar2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

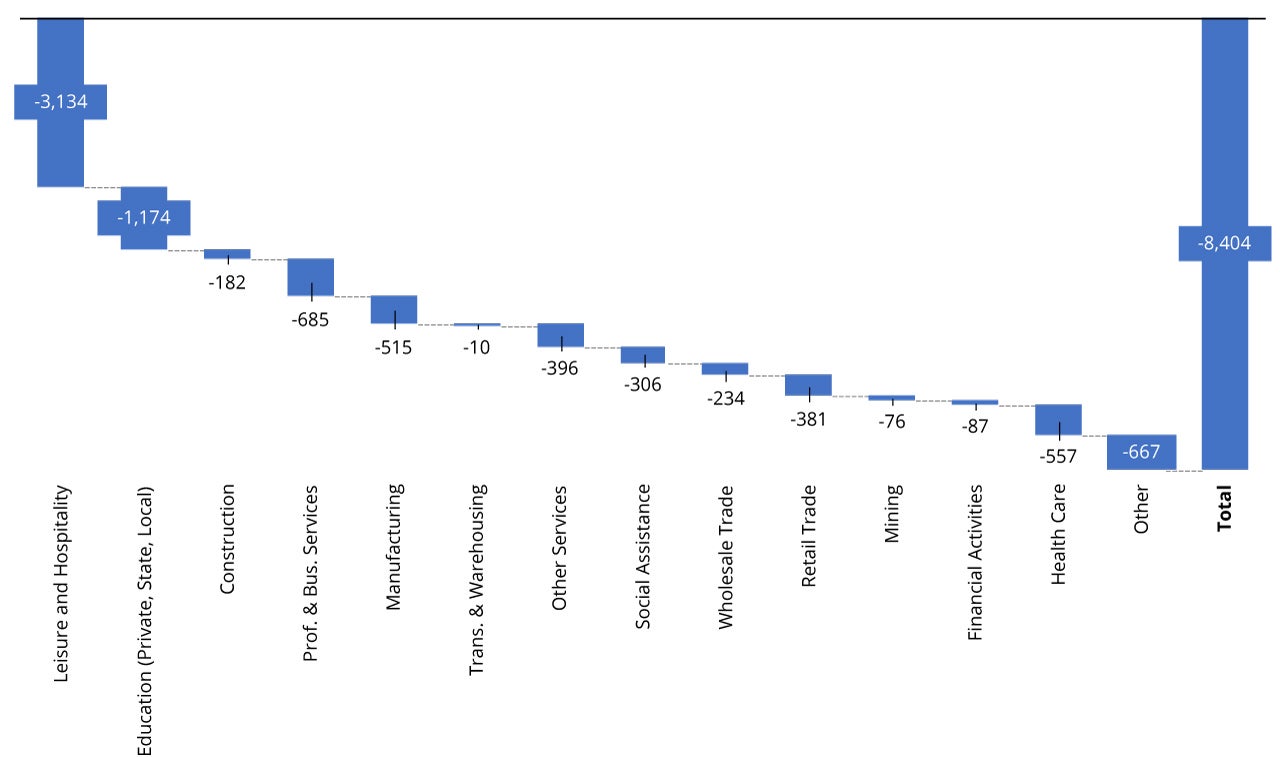

Figure 2. Jobs Gap Relative to Pre-Pandemic: Change in Employment, In Thousands, Feb 2020-Mar 2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

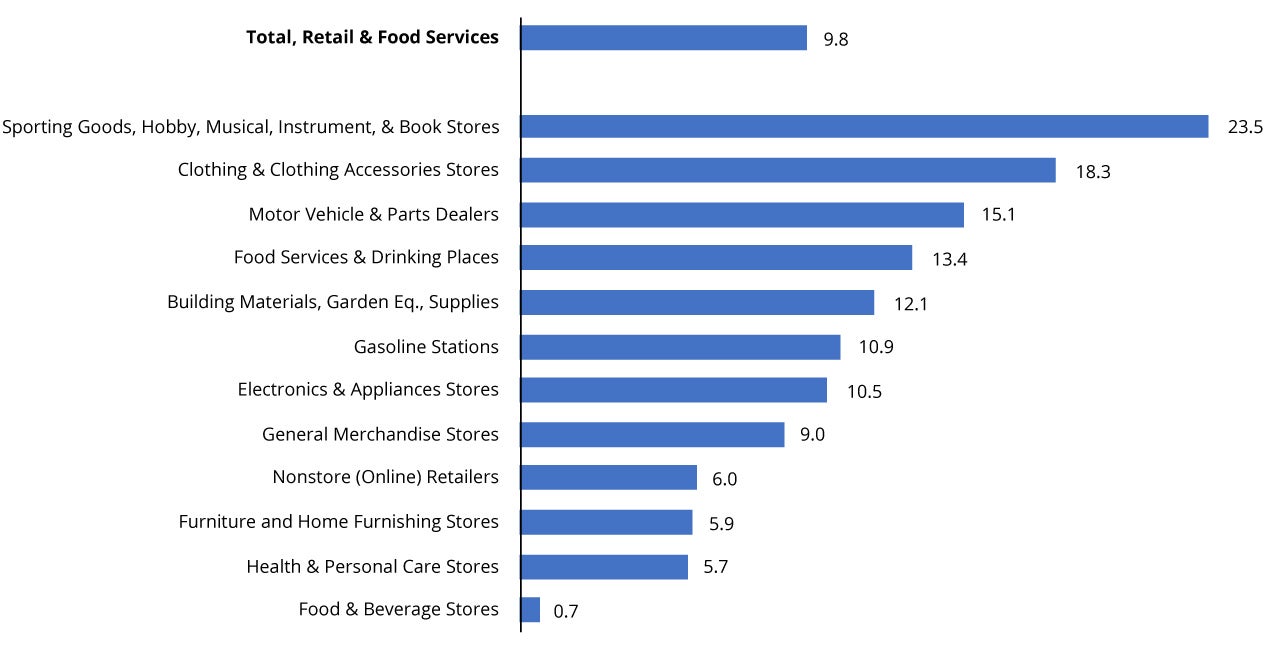

Figure 3. Advance Monthly Sales for Retail and Food Services, Percent Change, Feb 2021-Mar 2021

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

For this edition of Forecast Direct, we talk with Kathryn Edwards of RAND about income inequality, side hustles, and social insurance in the United States. Following is an edited summary of our conversation. Full audio and video of our conversation are available here, and Professor Edwards’ research is available here.

Leo Feler (LF): You have a paper where you talk about trends in income from 1975 to 2018, and you talk about how economic growth since 1975 has not been as equitable as it was during the two decades following WWII. Can you tell us about your paper, and why income growth has not been more equitable recently?

Kathryn Edwards (KE): We approach this question wanting to have some benchmark comparison to understand income growth. Nobody would say everyone should have the same income. “Perfect equality” is not the goal, but perhaps it’s something more equal than what we have now. What is the benchmark and what is good? That was one thing we wanted to approach in the paper, so what we decided on was to look at how incomes at various parts of the income distribution grew faster or slower than the economy overall. If GDP grew by 3%, how much would that predict incomes if everyone grew by the same pace as GDP overall? For the bottom 90% of households, they have been falling behind economic growth rates for almost 40 years, and so the foregone income that would be going to the bottom 90% of households – had their incomes grown apace with GDP would be almost double the median income today for your typical worker. If you add that up over time, it comes out to almost $2 trillion a year that would be going to the bottom 90% of households, but is instead going to the top. We also documented that the incomes of the top 1% grew three times faster than economic growth.

LF: Why did economic growth not accrue as equitably to the bottom 90%?

KE: Lots of research has shown that the bottom 20% will have faster income growth if the minimum wage is higher. There’s been research showing that unions contributed greatly to the middle class in the United States. But it’s never one thing, and it could be multiple things that move in different directions that cause this. I think there’s no one single explanation. One thing we ended up talking a lot about this summer was that some of the strongest income growth we documented was during the Jim Crow era. People tend to link in their minds that the increase in civil rights was a one-for-one mapping to the increase in economic rights and economic prosperity, but in fact the gap between the wealth of white and black Americans is larger now than it was in 1968. There are so many pieces and layers to this. We don’t have a great cause, but we think it’s both things that have been identified, like the minimum wage and unions, but also things that we haven’t thought about and talked about enough.

LF: Do you think economic growth might become more equitable during the next few decades, given the technological changes we’ve experienced and that have been accelerating because of this pandemic?

KE: I’m optimistic on a lot of levels. I think a higher minimum wage, above what it is now, would help. I think something that would help even more would be the end of the tipped minimum wage. The idea that it’s 2021 and there are people who make $2.13 an hour on paper, is pretty incredible. I think the idea of equitability and inclusivity has a stronger hold now than in the 1980s. I also think the Fed has truly changed a lot of its posture around the mandate of full employment. The Fed is starting to benchmark around the black unemployment rate. Indicators and data, these things drive decision-making and policy-making. I think these are becoming more inclusive as well.

LF: Let’s turn to your work about side-hustles and the gig economy. Has this helped households earn additional income, or has the rise of gig work eroded traditional opportunities for good-paying jobs?

KE: We looked at data from 1996 to 2015. Over this 20-year period, we were looking at who holds multiple jobs and what types of jobs these are. The survey we used does not ask about gig work, but it does ask about casual earnings, moonlighting, other income sources, and this is how we were able to piece together whether you were an informal or formal employee in the data. What we found is that multiple job holders and gig workers really aren’t the same group. There are a lot of people who work two jobs, and it’s very stable. You could imagine someone who’s employed part-time and also runs a small business. These are long-term jobs, people stay in them for a long time, and together these earnings push them to a place of economic security. The people that have informal work arrangements, people who said in the survey that they moonlighted – that came much more infrequently. If they did that type of work, it was not 9-to-5, and it was not every month or every year that they were in the survey, and it was very sporadic how these earnings were used. There could be people who are 100% full-time gig workers all of the time, but I think this is a relatively small group. Instead, there are people who use it as an as-needed supplement. I see it much more as a reflection of the lack of emergency savings in most U.S. households. We definitely see patterns that align more with people needing cash quickly, and less so with people eschewing a formal sense of employment because of the freedom of an online platform. The intuition of people needing cash but not having savings is much more in line with our findings.

LF: Given your findings about why individuals perform gig work, what are your thoughts on classifying these workers as employees? Would that create barriers to entry and make it more difficult for people to engage in these side-hustles, or would that actually benefit people in terms of allowing them to earn more when they are engaged in these activities?

KE: One of our findings is that the rate of multiple job-holdings (the incidence of doing gig work) falls when the minimum wage rises. If you are earning sufficiently at your primary job, or if your earnings increase because of something like a minimum wage increase, we see a lot less casual earning. There’s also the worker’s perspective and the firm’s perspective. The firm perspective is that platforms like Lyft and Uber are not paying social security taxes on these workers, and they’re not paying into the unemployment insurance system. The classification question becomes wrapped up in access to work, when the question should be: what are they giving into the system and what are they getting out of it? There have been at least three reports from the Government Accountability Office about how many people who work full time at Walmart are on Medicaid, and the fact that they pay such low wages is subsidized by the government. That’s the same question from a different perspective when you look at Uber and Lyft drivers that are not paying into the employer risk system that exists. The pandemic recession offers more of an insight into that. Uber’s CEO advocated for relief for his drivers, not from the unemployment insurance system that Uber didn’t pay into and that they don’t want to pay into, but some type of special relief for his drivers who weren’t going to be able to work. Uber realizes there’s a need to provide risk and insurance to their workers, they just don’t want to do it in the venue that’s available. This is another example of pushing more risk onto workers, one that even Uber’s CEO said that workers were not able to face on their own. I think there’s more room for creative policy about classification. I think the classification argument itself would be a lot different if there were a 1099 issuance tax that employers had to pay. So, they can be classified as gig workers, you can give them a 1099 form, but every 1099 form you issue, you have to pay some amount into social insurance funds. If you can’t force the incentives through legality, you can work with incentives through the tax system.

LF: Let’s talk more about unemployment insurance. We saw unemployment increase to over 14% in April of 2020, the highest we’ve had since the Great Depression. We’re now at about 6% unemployment, although this varies drastically between white unemployment and black unemployment, which is still close to 10%. Given the number of people who entered the unemployment system, how do you think our unemployment insurance system fared during this time? What are some thoughts about reforms that our system needs going forward?

KE: Unemployment insurance has the advantage that it has a stable base, because it is a social insurance program. There were administrative difficulties, but states were hit with an incredible number of claims. They still paid out millions of claims in a matter of weeks during the crisis. The real problem with unemployment insurance was that the benefits were low, they didn’t cover enough people, and they varied so much by state. That has been the problem with the program for decades. I think there is justifiably a lot of focus on the administration and the IT systems. I think that’s obfuscating what’s really going on, which is that you had a social insurance program run by states, with a very stable base but that not enough people got, and then you had a federal program that was placed on top of it on very short notice. Most of the fraud we’ve seen is associated with the federal pandemic unemployment assistance, and that makes sense. States didn’t have wage records for these people for the entirety of their work history in the state. The administrative burden of pandemic unemployment assistance was truly incredible and unprecedented. For me, the lesson is it is very difficult to build a program during a crisis. It’s one more argument for broad federal reform. To answer the question, unemployment insurance did good for how long we had neglected it, and how weak the program had become. Ultimately, what we learned from this recession is just how out-of-date these state-based programs had gotten. I compare it to a house that is standing on a foundation but that has had all the doors and windows blown out. It could be okay, but you should probably do some work on it before it rains.

LF: You wrote about how the fact that the federal government stepped-in and gave an additional $600 a week, created pandemic unemployment assistance for gig workers, and extended the time frame for unemployment insurance, that this might serve as a disincentive for some states to take care of their own unemployment systems.

KE: I think the question is why should a state increase taxes on their employer base coming out of a recession to prepare for the next one if the federal government is going to pay for unemployment insurance during a recession? Why should a state put its employers at a disadvantage? The way that I explain it to people is that the only permanent constituency of the unemployment insurance system are the employers who pay the taxes. The statutory incidence of unemployment insurance is only on employers. It’s not like social security, where you see FICA on your paycheck, and both you and your employer are paying. You’ve never seen a line on your paystub for unemployment insurance, and you might not have known you were paying into it, based on your wages. So that gives a natural race to the bottom among states to have the lowest taxes. We’ve been here before. After the Great Recession, 34 state programs had to borrow from the federal government, and the Government Accountability Office said, “You are not going to be prepared for the next recession unless you increase your taxes and have better future funding into the program.” Some states did that, some of them raised their taxes and prepared, and had a stable benefit base. A lot of them didn’t. A lot of them said that we’re just going to go the other way. Rather than pay for a large trust fund, we’re just going to make sure there aren’t that many claims on it. There was some absurdly low number of people getting unemployment insurance claims in Florida. It was in the tens of thousands, and they only had access for nine weeks, and the benefits weren’t that generous. But Florida, for as much heat as it gets in the press, doesn’t have a trust fund that’s insolvent at the moment. All the states that cut their benefits after the last recession, those are the states that are not borrowing right now. It’s a lesson that comes from multiple directions, both seeing that the people who did not step-up for their program and tax their employers more, but rather tried to get workers to have less, from the perspective of solvency, they’re doing better than states with more generous benefits. Added to that is the CARES Act, and the intervention from the federal government this time around. It’s two incentives that are very clear. If I’m going to learn any lesson from this recession, it’s going to be to cut taxes, cut benefits, and wait for the federal government to step-in. So the question really becomes, when is the federal government going to step-in on a permanent basis as opposed to an ad-hoc one during recessions?

LF: That brings me to our final question: should we federalize unemployment insurance, or should we still have these state-based systems?

KE: I think there needs to room for states to do what is appropriate for their state, and then move benefits up to the federal government. A more concise way of putting that would be that there is a role for states, and there is a role for the federal government. For benefit allocation and administration, for workers who move across states, for those who work in multiple states, in terms of equity and ease of administration, the federal government has shown that they can provide quick and equitable administration much more so than the state unemployment insurance system. I wrote an article last summer pointing out that simply by virtue of where they live, black workers will get less in unemployment insurance than white workers because a larger proportion happen to live in states that have much lower benefits. Do you think that people who earn the exact same amount of money and work the exact same amount of time should have two different unemployment insurance benefits because they live in different states, and what are the consequences if they do? We’ve seen the consequences of inequality and disparity. We could change that with a federal uniform benefit that’s based on people’s earnings. I’ve had people ask me, “What about cost of living across states?” Well, that’s incorporated into your wages. It’s the same thing as social security, it’s already based on your wages. But I do think that state governments have administrative and technical expertise. Other things that have happened to unemployment insurance besides benefits being reduced is the amount of employment services that are given – assistance in job search, counseling for job search, help moving across the state to go to a job that’s available somewhere else. There’s lots of roles for state governments from that perspective, through things like the American Jobs Centers. There are so many options for unemployment insurance, but we have not meaningfully reformed the system since at least 1976 or maybe 1955. We have decades of experience and so many recessions that we’ve learned from, and we’ve incorporated so little of that knowledge into how this program is fundamentally structured. There are so many improvements we could incorporate, but at the moment states have little incentive to do it on their own.