December 2021

December 2021

Entrepreneurship and Opportunity Zones

Leo Feler, Senior Economist, UCLA Anderson Forecast

Kenan Fikri, Director or Research, The Economic Innovation Group

Entrepreneurship and Opportunity Zones

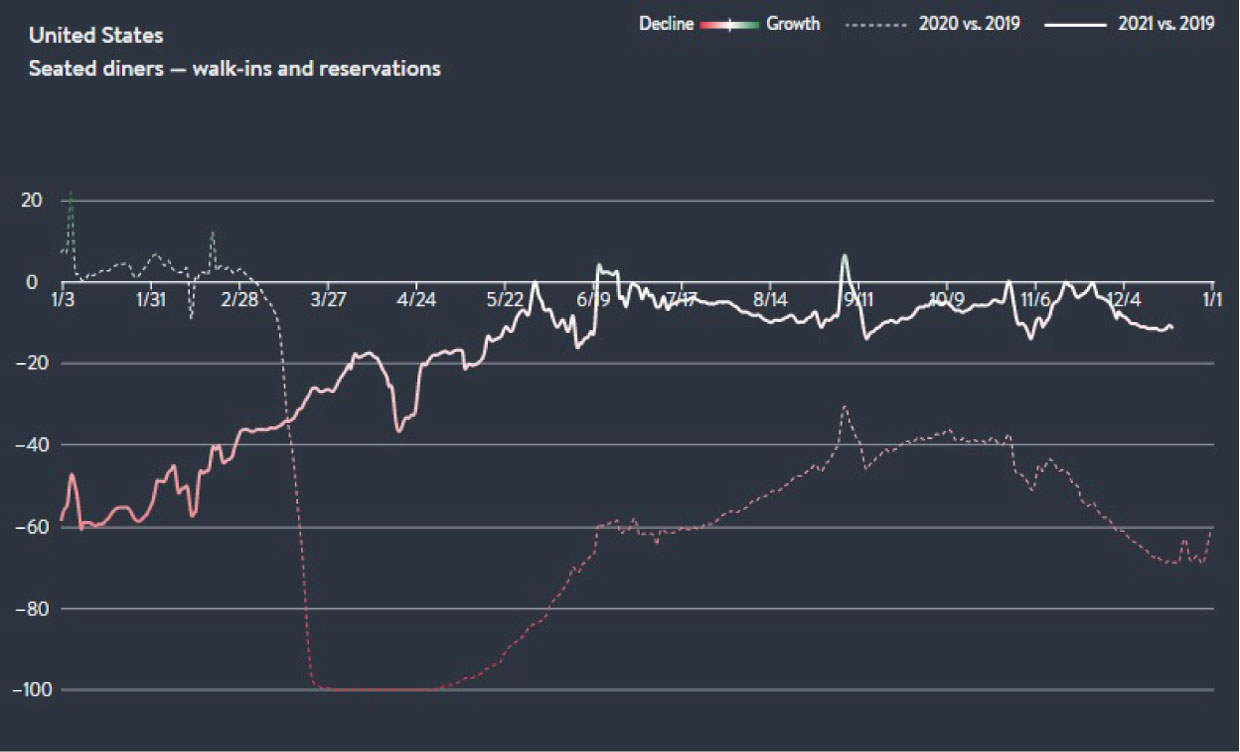

- With COVID cases surging once again, we re-iterate our forecast for Q1 2022 of slower real GDP growth of 2.6% at an annualized rate. In our December forecast, we had already assumed an Omicron or Delta wave would reduce consumption of in-person services. We are beginning to see this reduction in seated diners, based on OpenTable data (see Figure 1).

- At its recent FOMC meeting, the Federal Reserve signaled an end to tapering by March and rate lift-off shortly thereafter, with the dot plots indicating three rate increases to 0.75%–1.00% are likely by the end of 2022.

- The next inflation reading, for the PCE price index in November, comes out on December 23rd. We’re again expecting a hot inflation number, with the year-over-year change in the PCE price index at around 6% and core (excluding food and energy) around 5%, the highest in nearly 40 years. But with COVID cases surging once again, oil prices have started coming down and services consumption is likely to slow, which will contribute to pulling down inflation numbers heading into Q1 2022.

- Supply constraints are starting to ease, specifically in auto production, which should help bring inflation down in the coming year (recall that a major contributor to inflation this year was used car prices). In November, manufacturing output rose 0.7% to its highest level since January 2019. Within durable goods production, the largest increase was in motor vehicle and parts, but even with this improvement, production of motor vehicle and parts is still 5.4% below its year-ago level.

Exhibit 1: OpenTable Seated Diners, 2021 vs. 2019 and 2020 vs. 2019

Entrepreneurship and Opportunity Zones

Kenan Fikri

Director of Research, The Economic Innovation Group

This month, our podcast features a conversation with Kenan Fikri, Director for Research at the Economic Innovation Group. We discuss entrepreneurship and opportunity zones.

Leo Feler: I’d like to talk with you today about two topics you work on, entrepreneurship and opportunity zones. Let’s start with entrepreneurship. What has happened with entrepreneurship during this pandemic?

Kenan Fikri: In the first two months of the pandemic, we saw entrepreneurship fall off a cliff, as you would expect – where people adopt a more conservative stance and get more risk-averse. But then what happened next, no one really expected. There was a surge in applications to start new businesses, which is the Census Bureau’s real time indicator of entrepreneurial activity, that shot through the roof between April and July 2020. They subsided a little bit from there, but stabilized at historically high levels. In 2019, there were 3.5 million applications for Employer Identification Numbers, which is the measure used to gauge interest in starting new businesses. By 2020, that number had shot up to 4.4 million. Come 2021, we’re on course to reach more than 5 million. A lot of these are going to be solo entrepreneurs, like Etsy sellers. To weed out some of the noise, the Census Bureau also looks at the ones that are most likely to become employers based on the characteristics of the applications, and those have exhibited similar patterns. So far in 2021, we’ve seen more than 1.6 million of these likely employer new business applications, which is 40% more than this time in 2019. What’s exciting for those of us who have watched this data closely and care about entrepreneurship is the longevity of the boom. You can explain the early pandemic spike with things like maybe people are formalizing businesses to get PPP money, but the fact that it’s still going on now makes it seem quite meaningful and real.

Leo Feler: Coming out of the Great Recession in 2008–2010, did we get something like this?

Kenan Fikri: We got nothing like this. The Great Recession precipitated a lost decade in American entrepreneurship where startup rates fell by about 20% and didn’t budge from there, all the way through the eve of the pandemic recession.

Leo Feler: Why is this time different?

Kenan Fikri: The pandemic was a shock from outside the economy. The Great Recession was a more traditional financial crisis. Credit was curtailed significantly, asset prices fell, wealth evaporated from the US economy. What we’ve seen in the pandemic is just the opposite. Massive amounts of credit and stimulus were pushed through the system. Asset values from homes to stocks have been on a bonanza. Pandemic-era supports for households meant that income losses were subdued. The pandemic-era supports at the household level and economy-wide produced a situation where we de-risked entrepreneurship: people were able to take entrepreneurial decisions knowing that they would have their home values to fall back on, or their retirement portfolio was doing great and they thought, “why not?”. I think one other factor that’s really different now comes down to the social and emotional trauma of the pandemic that prompted people to take stock of their lives and maybe choose a more independent, fulfilling or gratifying career by striking out on their own.

Leo Feler: What are the sectors where we’re seeing the most growth in entrepreneurship? Who are these entrepreneurs?

Kenan Fikri: The first thing to note is that it’s broad-based across sectors. It’s not just one individual corner of the economy. Non-employer applications – for businesses that aren’t expected to pay any wages –are dominated by non-store retailers. This captures the shift to digital and the at-home economy. It’s significant, but it’s not the whole story. Among the likely employers, the applications have been highest in sectors on the front lines of the pandemic: accommodations and food services, retail, health, and transportation and warehousing. Some of this reflects economic restructuring: these are sectors that have gone through a lot of disruption, and there are new market opportunities that the pandemic opened up. We may also be capturing some people who maybe closed one business due to shutdowns and reinvented themselves in a new endeavor. This data will only capture the new enterprise, not the one that closed.

When it comes to who’s doing it, Robert Fairlie, an economist at UCSD, has looked at the demography of active business owners in the US. Early in the pandemic, he uncovered some troubling statistics, like the number of active Black business owners fell by 40%, a massive amount, in early 2020. But since then, the business-owning population for most groups has really recovered. There are now 30% more Black business owners in the Current Population Survey than there were in February 2020. For Latino business owners, 17% more; female business-owners, 8% more. We’re still missing 4 million workers from the economy, but the business owning population has more than recovered.

Leo Feler: Why this interest in entrepreneurship, versus an interest in job creation more generally, regardless of whether it’s at new firms or existing firms?

Kenan Fikri: I like to break entrepreneurship into three different groups. You have the self-employed, you have the mom-and-pops, and you have the more disruptive growth firms. Each one plays a different economic role or function. Self-employment is a great option for some people to have, for personal reasons it might be very important. Mom-and-pops are vital to the health and vibrancy of our communities. Even at the small scale, entrepreneurship is a big cornerstone of household wealth in the country.

I firmly believe in the role of the entrepreneur as an essential catalyst for economic change, helping us keep markets competitive, keep innovations coming into the market, even pioneering new modes of work. Through the 2000s and until the Great Recession, high-growth young firms were actually disappearing even faster than the mom-and-pops. These high-growth young firms drive net job creation in the economy, and they’ve been on the decline for a couple of decades now. At the end of the day, incumbent firms often don’t create the net job growth the country needs to employ a growing workforce. For every job that Amazon creates, there may be a loss in other firms in other parts of the economy. That delta, year in and year out, of where we’re getting job growth, is really carried by these high-growth young firms that were missing from the Great Recession recovery. Hopefully we’re seeing some resurgence of that activity now—it will only make the pandemic recovery stronger.

Leo Feler: What makes it easier for people to start new firms?

Kenan Fikri: I think what’s making it easier right now has to be the advance of technology and platforms. That’s a big difference from the Great Recession. We didn’t have UpWork, we didn’t have Uber at that point, where people can more independently be an entrepreneur in one way or another. Platforms like Etsy didn’t have the scale they do now. To that extent, platforms have, in a way, enabled entrepreneurship to serve as a bit of an economic safety net after a job loss. At least you can do something and find a willing buyer for your labor, even if your local economy isn’t doing that great.

Leo Feler: What about barriers to entrepreneurship?

Kenan Fikri: Access to capital remains a big one and might be a constraint in translating some of these temporary entrepreneurs or people who were pushed into entrepreneurship out of necessity into folks who can grow and scale a business. We see now in the CPS data that female entrepreneurship is up more than male entrepreneurship. Same with Black and Latino business owners relative to whites. Often female or minority-owned businesses start with less capital, and they have a harder time obtaining growth capital. I don’t think that credit markets or financial systems have transformed enough with the pandemic to change these fundamentals, unfortunately. The barriers to scaling and establishing a high-growth business still remain, and means that a lot of people who started new businesses during the pandemic are going to struggle to succeed and grow over the long term, especially the entrepreneurs out of necessity, who may not have a lot of money to fall back on.

Leo Feler: Let’s transition and talk about opportunity zones. To start off, what is an opportunity zone?

Kenan Fikri: An opportunity zone (OZ) is a low-income census tract that qualifies for a federal capital gains investment incentive. The idea itself was borne out of geographically uneven recovery from the Great Recession and a lack of progress in reducing concentrated poverty, persistent poverty, since the turn of the century. People thought it was time to address this problem with a novel approach. OZs offer a series of capital gains tax incentives and benefits for long-term equity investments in low-income communities that culminate in the prospect of potentially no capital gains taxes investments held for 10 years or longer. We know what happened when the federal government drew maps – or redlined – of where not to invest. That decimated neighborhoods and families for generations. Opportunity Zones tries to turn that on its head and ask what’s possible when the federal government draws a map of where to invest instead. It’s an incentive that tries to bring distressed communities back into the fold of the broader economy by rewarding investors who place their money there to do something that’s additive or build a company.

Leo Feler: What are the initial results you’re seeing in terms of the economic impacts these opportunity zones have generated?

Kenan Fikri: It’s still early and there’s only preliminary data on what’s happening. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report on the first year of OZs existence and found that $29 billion had been invested because of the incentive in 2019. The figure is likely over $70 billion through 2021. A lot of this money is going into real estate: rentals or multi-family. Locally in California, we know it’s doing a lot to expand the housing supply with infill developments in low-income census tracts in places like Santa Ana or San Jose. There’s also a cluster of affordable housing investments and investments in minority business development incubators in South Los Angeles. You get the whole gamut of everything from market-rate housing to affordable housing to some investments in public structures to minority business incubators. It’s a whole range of things.

Leo Feler: There’s already some criticism that OZs don’t provide enough support for underserved communities relative to the tax breaks they generate for what are disproportionately wealthy investors. What’s your take on this criticism?

Kenan Fikri: I think it’s too soon to tell how OZs are going to shake out. The question of who benefits and by how much is going to be critical in assessing whether or not this experiment is beneficial and how to change it or reform it in the years ahead to make it more effective. The need is large and acute enough that a bold experiment here is appropriate. A statistic I always keep in mind is that two-thirds of the census tracts in metropolitan America that were poor in 1980 are still poor today. The economy has changed a lot, investment habits changed a lot, a lot of policies have come and gone. But at the end of the day, the dial is not moving for massive swaths of the map, and that’s a couple of generations already turning over in these communities.

At heart, OZs are a place-based incentive. If we know that poverty has causes that are rooted in geography, it does seem intuitive that we want to experiment with tools that address geography and geographic concentrations of poverty. If you look at past programs, generally the more strings you attach to investment incentives, the less they’re utilized and the less they do. OZs have adopted a completely different approach. They say as long as you’re investing qualifying money into qualifying places, and you’re doing something that’s additive – you’re building something new or infilling, or you’re occupying something that’s vacant, or you’re building a new company – you’re going to get this federal tax benefit. At the end of the day, it’s going to take some rigorous study of how conditions and outcomes in these communities have changed relative to the tax benefits that investors received from OZs to settle the debate.

Leo Feler: Kenan, thank you so much. Very insightful conversation. Thanks for taking the time to talk us through these two topics, entrepreneurship and opportunity zones.