August 2022

August 2022

Oil Markets and Gasoline Prices

Leo Feler, Senior Economist, UCLA Anderson Forecast

Severin Borenstein, Professor, Haas School of Business, UC Berkeley

A Mixed-Message Economy

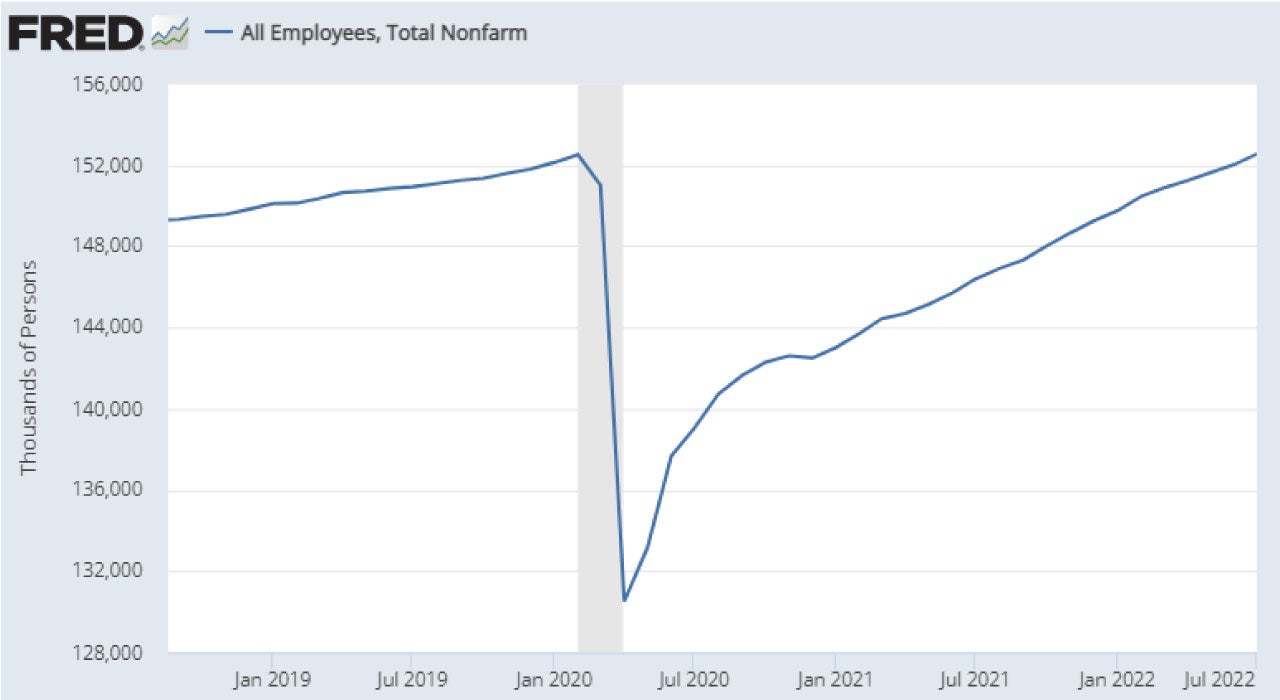

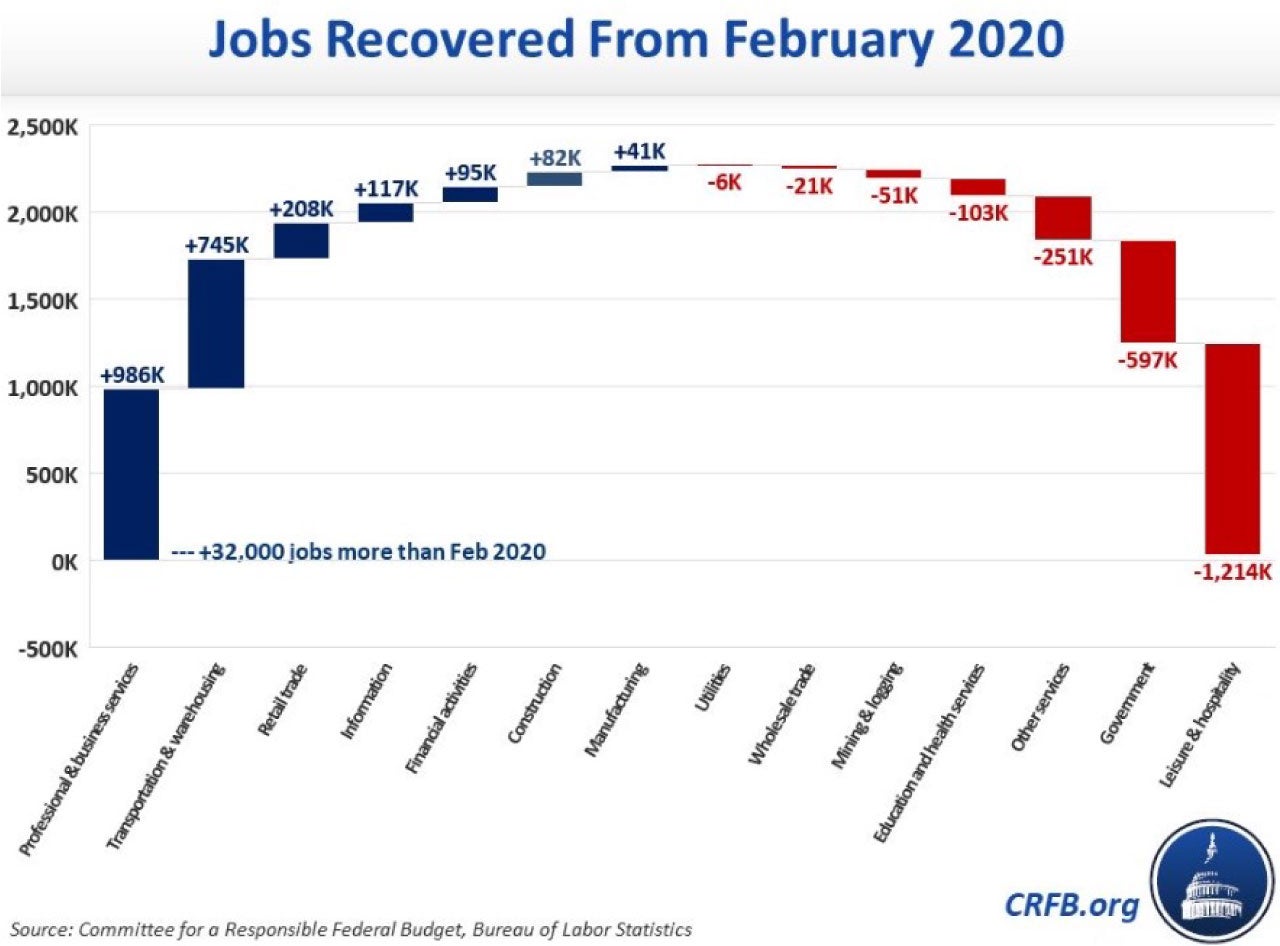

- 528,000. That’s the number of total nonfarm payroll jobs created in July. We are now back at pre-pandemic employment levels (Figure 1), but the composition of employment has changed considerably (Figure 2). In July, employment gains were broad-based across sectors. Employment growth accelerated in construction, manufacturing, wholesale trade, education and health services, leisure and hospitality services, and government. Employment growth held steady in retail trade, transportation and warehousing, and professional and business services, with these sectors adding about the same number of jobs as they did the month before. The only sector that saw a decline in employment was motor vehicle and parts manufacturing, due to continued supply constraints in this sector.

Figure 1: Total non-farm employment is back at pre-pandemic levels

Figure 2: The composition of employment has changed considerably since the start of the pandemic

- 3.5%. That’s the unemployment rate. We’re back to the unemployment rate we saw right before the pandemic. This is a tight labor market. With workers having negotiating advantage, wages increased 5.2% over the past year.

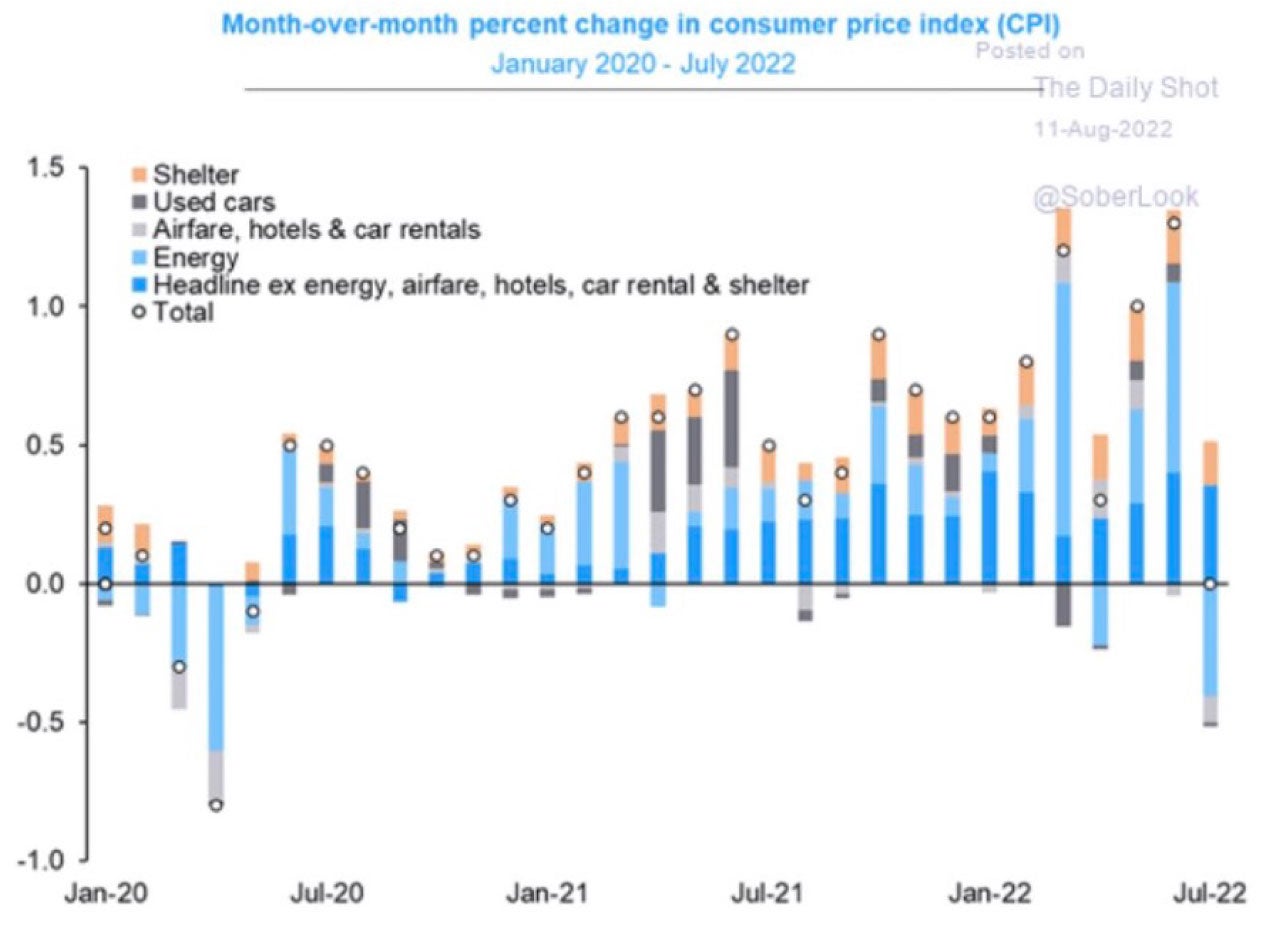

- 0.0%. That’s the month-over-month CPI inflation for July, following 1.3% month-over-month inflation in June. The decline in the rate of inflation was due to lower gasoline prices, lower used car prices, and lower “summer travel” prices – airfares, hotel rates, and rental cars. Deflation in these prices offset higher prices for shelter (rentals and owner-occupied housing), food, and medical care (Figure 3). Food at home inflation accelerated, from 1.0% in June to 1.3% in July, although there will likely be some reprieve in August as suppliers pass through lower transportation costs to consumers. Core inflation, excluding food and energy, was 0.3% month-over-month in July, down from 0.7% in June. This is a good news and bad news CPI report. The good news is that inflation has likely peaked. We’re at 8.5% year-over-year, and it will likely come down moving forward. The bad news is that inflation has become more broad-based over time, and we have some concerns that shelter, medical care, and services inflation will continue. This means that the 8.5% year-over-year inflation might come down steadily to 4-5% year-over-year by early 2023, but getting down to around 2% year-over-year inflation will be a challenge and will take much longer.

- The producer price index for final demand declined 0.5% in July, following a 1.0% increase in June. Most of this decline is attributable to lower gasoline prices. With gasoline prices continuing to come down in August, we’ll likely see producer price inflation remain subdued in the next report. Lower producer prices tend to mean lower consumer price inflation in the future.

- Despite one month of encouraging inflation reports, we’re still a long way from the Fed’s target of 2% core PCE inflation. And we’ve had several months of strong jobs reports. The current mix of data still does not give the Fed much room to ease off on rate increases. We still project a terminal Fed Funds Rate of 4.0-4.25% by mid-2023.

- The advance estimate for GDP showed that production contracted by 0.9% at a seasonally adjusted annual rate in Q2 2022, following a 1.6% decline in Q1. It’s important to keep in mind that this negative Q2 GDP number is an advance estimate. This number will be revised. When we think about recessions, we often use the rule-of-thumb of two consecutive negative quarters of GDP growth, but that is based on final GDP numbers, not advance estimates. Recessions also tend to be broad-based across the economy. The contractions we’ve seen in the first two quarters of this year were not broad-based. They’ve been primarily driven by a reduction in inventory accumulation on the part of businesses. Consumption has remained strong.

- We’re likely to see further weakness in the economy as the Fed continues to raise interest rates and a lot of the pent-up demand for services – like vacations, dining out, and entertainment – subsides. Consumers are also using up the savings they accumulated during the past two years. This combination of higher interest rates and waning consumer demand is what we think might lead to further and broader sluggishness of the economy later this year and into 2023. In short, it doesn’t look like we’re in a recession yet, but it’s still early in the tightening cycle.

Figure 3: Deflation in gasoline, used car prices and “summer travel” prices has offset inflation in shelter, medical care, food, and services

A Conversation with

Leo Feler and Severin Borenstein

Professor, Haas School of Business, UC Berkeley

This month, our podcast features a conversation with Severin Borenstein, Professor at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business. We discuss oil markets and gasoline prices.

Leo Feler: Severin, thanks for joining us. To start off, why did oil and gas prices increase so much over this past year?

Severin Borenstein: So, first, we have to go back further, to the beginning of the pandemic, when we saw oil prices drop very suddenly because 50% of the demand disappeared overnight. Crude oil prices dropped down to the low $30s, and there was that one day that oil prices went negative. We did see very cheap oil, and we saw cheap gasoline prices associated with that. Even then, the futures market didn’t think that was going to last and that oil prices would go back up, although not to the levels we’re talking about now.

What happened were two things, both on the demand and the supply side. On the supply side, when oil prices really plummeted, we saw a lot of production get taken offline. We saw this in the United States, but we also saw this in other countries. It turned out that bringing that production back online was more challenging than a lot of people thought. Supply chain disruptions meant that it was more difficult to get needed equipment to bring production back online. Then, oil fields are generally in pretty remote places. Workers didn’t hang around these places when the pandemic started and production was taken offline. Workers left, and companies have struggled to recruit workers back. At the same time, in the refining sector in the United States, a lot of old refineries were already creaking along and were scheduled to get shut down some time in the next five years or so. When demand plummeted during the pandemic, many refineries decided it was a good time to shut down. Demand is way down. Margins were disappearing. Should they really keep going through the pandemic, when it was unclear how long it was going to last, or should they shut down early? Many of these refineries did end up shutting down early, and we lost about a million barrels a day of refining capacity. So, that’s the supply side.

On the demand side, demand came roaring back sooner than people anticipated. In fact, demand for gasoline right now is pretty much where it was before the pandemic. What’s interesting about that is, as we all know, we’re not going to work as much as we were before the pandemic – there’s a lot more work from home. But, public transit is still off about 50% from pre-pandemic levels. Part of this is that the economy has picked up, people are moving around more, there’s a lot of pent-up demand to go places.

The combination of growing demand and declining supply – even before Russia’s attack on Ukraine – was leading us to a real jump in oil prices, that were up to almost $80 a barrel, before we even started talking about the Russian threat. Then, of course, Russia invaded Ukraine. The United States and the western countries slapped sanctions on Russia. That makes it harder for Russia to sell their oil, and some of that got taken off the market, but not most of it. In some ways the ideal from a US point of view would be if Russia was still able to sell their oil, but at a deep discount. That way, Russia doesn’t get as much money, but the world still gets oil. That’s not what we’ve accomplished. Russia is selling their oil at a discount, but because the price is so high, even with a discount, they’re making boatloads of money on it. All the other oil companies are making huge profits right now too, not because they’re doing anything to manipulate the market (with the exception of Saudi Arabia, which is always manipulating the market), but because they simply are in the right place at the right time.

Leo Feler: Can we expect oil supply to start increasing, given how high prices are? Are we seeing more oil production in the US?

Severin Borenstein: We are seeing production ramp up. It is coming back more slowly than a lot of people thought it would. I think the increased supply and some concerns about a recession are leading the futures market for crude oil to show much lower prices than we’re seeing today. If you go out a few years, the prices are back down in the $70 range compared to about $100 per barrel today.

Leo Feler: We’ve seen oil prices come down recently. They were at $130 per barrel, and as you mentioned, they’re now about $100 per barrel. We’re starting to see gasoline prices at the pump come down, but it hasn’t been a one-for-one relationship. Can you talk about this relationship between crude oil prices and gasoline prices, and why we’re seeing this lag in gasoline prices coming down?

Severin Borenstein: First of all, we have to be clear that when the media says oil prices have come down 20%, and they think gas prices should come down 20%, it’s not a percentage relationship. There are lots of other costs that aren’t changing, in fact, that are going up with inflation right now. The standard rule of thumb is that every one dollar drop in the price of a barrel of oil lowers wholesale gasoline prices 2.4 cents per gallon. With taxes, I generally round that up to about 2.5 cents per gallon at the pump. What we would expect is a $30 a barrel drop in the price of crude oil would eventually come through to about a 75 cents a gallon drop in the price of gasoline. “Eventually” is an important word here. Twenty five years ago, I published a paper that actually looked at these adjustments, and I found that when the price of crude oil rises, the price of gasoline rises fairly quickly. A full adjustment typically shows up within a week or two. But when the price of oil falls, the price of gasoline falls more slowly. It generally takes 3 or 4 weeks. It is a long lag. There’s some research that shows that when the price of gasoline rises, consumers search a lot. Consumer search makes the market more competitive, so the market adjusts. But when the price of gasoline falls, consumers tend to relax and not search as much. That makes the market less competitive. That means it takes longer for the price of gasoline to follow a downward change in the price of crude oil. That’s why we’re seeing a lag in the adjustment of gasoline prices to crude oil. In the long run, and the long run is typically a month or two, they do adjust. We are continuing to see gas prices falling over the last few weeks, even though crude oil prices haven’t fallen at all during this time.

Leo Feler: In states like California, how come gasoline is so much more expensive?

Severin Borenstein: California is a real outlier among the states. California burns a cleaner gasoline than the rest of the country, which we adopted in the 90s, and for some reason states like Utah, that have huge pollution problems have never followed. We use a cleaner-burning formulation. Typically, people say that costs ten cents a gallon extra to produce. California has much higher taxes and environmental fees than the rest of the country. Our full tax on gasoline these days is probably around 60 cents a gallon, compared to a national average of about half that. Plus, we have a price associated with the cap and trade market which we have for greenhouse gases. And then we also have a cost associated with the low carbon fuel standard. All of those add up to a bit over a dollar a gallon. However, since 2015, California’s prices have been higher than the rest of the country by more than can be explained by these higher taxes and fees – what I call the mystery gasoline surcharge. It appeared in 2015, after a refinery fire in Torrance. Even when that refinery was back online, it has never disappeared. For seven years now, we have been paying on average an extra 30 cents a gallon that cannot be explained by higher taxes and fees or the higher cost of our cleaner-burning gasoline. Since 2015, this means that Californians have paid over $40 billion more in these mystery charges, which is more than $1,000 per Californian.

Leo Feler: Do we have a sense of who this money is going to? Is it going to refiners or oil producers?

Severin Borenstein: The California Assembly just created a select committee to dig in to why California gas prices are so high. I’m really pleased about that. I hope we can stay focused on the mystery gasoline surcharge, and not get into conspiracy theories about the world oil market, which, even if they were true, are nothing California can do anything about. Here’s what we know: we know that the actual commodity price of California gasoline is about ten cents a gallon higher than the rest of the country, reflecting the cost of our cleaner-burning gasoline. So, it’s not taking place just in the raw gasoline commodity market, it’s taking place downstream. That doesn’t mean the refiners are not a big part of it, because the refiners, although they don’t own gas stations, they have long term contracts with gas stations that essentially allow them to control the price. They will say, “we don’t set the price,” and that’s true. But, they have individualized wholesale contracts with separate stations that they can adjust. So, they can charge a Chevron station in Orinda, California more than they charge a Chevron station three miles away in Berkeley. That, of course, means that rather than a large number of stations competing with each other, it can be just a few refineries who are setting prices. The exception to that is off-brand stations. What’s really interesting is that California has far fewer of these off-brand stations. Here in the Bay Area, Rotten Robbie is one of the small chains. They buy commodity gasoline and sell it through off-brand stations. But also, Costco and Safeway are much cheaper off-brand sellers. We have far fewer of those as a share of the market in California than the rest of the country does. Interestingly, if you look at Gas Buddy data, the differential between branded and unbranded in California is far larger – more than three times larger than the differential between branded and unbranded in the rest of the country. One of the problems seems to be that we in California don’t have as much unbranded competition disciplining the major brands.

Leo Feler: Do you have a sense of why? Is it regulation? I think there was a recent regulation limiting the number of new gas stations in certain areas in California. Is that what’s preventing some of these independent, non-branded gas stations from having a greater share of the market?

Severin Borenstein: There has been a recent trend, although it’s very recent and it hasn’t gotten much traction yet, to ban new gas stations. That’s not the reason we don’t have unbranded stations, but there is a lot of regulation around owning and starting a gas station. That could be part of it, and I hope the Assembly select committee will dig into that. There are also potential issues about the ability of those off-brand stations to get gasoline through the California system. In California, the only way you can bring in gasoline is through the ports. We have a couple of refineries inland, but most of the refineries are on the coast. The refineries are almost all owned by the major brands. Two brands own 50% of the capacity. If you own an off-brand gas station, you often have to bring in gasoline from out of state, and that means you have to have access to ports, you have to have access to pipelines. And then, there’s the argument that some people in the industry make, which is that Californians don’t shop around as much. If you can save 50 cents by driving three blocks, Californians tend to skip that, whereas in other states, consumers are more likely to do it. Maybe that’s true. Maybe it’s related to the traffic, and people think it’s a bigger hassle here in California. But for some reason, those unbranded stations don’t get as much business, given the sometimes huge price differentials. In Orinda, California there’s an off-brand station that’s three or four blocks away from the major-branded stations, and it’s 60 cents a gallon cheaper. And yet, the major-branded stations are continuing to do a lot of business. I go to the off-brand station, both to save money and because it puts pressure on the major-branded stations to lower their prices. If more people did that, we would see the branded stations lowering their prices more, and we would also see more off-brand stations coming into the market.

Leo Feler: A lot of states have been talking about doing tax holidays for gasoline. The federal government has considered doing a tax holiday for gasoline, taking some of the pressure of higher taxes off of consumers. What kind of effect do you think this would have on consumers?

Severin Borenstein: A good starting point to recognize is that, if you compare the gas taxes we pay, even in California, to the negative externalities associated with burning gasoline – and this isn’t congestion or accidents, because those would also be there with electric vehicles – just the pollution externalities, including greenhouse gases, our taxes are actually less than those negative externalities. So, gasoline is not too expensive due to taxes, it’s actually too cheap. If we really priced in all those negative externalities, the price of gasoline would be much higher.

I still think there’s potentially an argument, at times, for giving consumers a break if you think they’re particularly deserving. You can then have an argument about whether we should be helping people who are facing high gasoline prices more than we’re helping people who are facing high rents or high medical bills or high grocery costs. But, this is one of the focuses right now, politically, because the people who are hurt by high gasoline prices tend to be a fairly loud political constituency. The question then is, if you were to cut gas taxes, how much would actually make it to the consumer. At the state level, any one state cutting its gas tax, even California, is such a small part of the world oil market, that it’s unlikely they’re going to actually push up the price of crude oil enough that oil producers would be able to extract much of that demand increase coming from the tax cut. Any one state cutting their gas tax is likely going to see almost all of that going to consumers. There’s some possibility that the refining industry, which for a while was very constrained – although that’s less true now than six months ago – could take a bit of the benefit. But I think the majority of the benefit would end up going to consumers.

That’s not as clear when you consider a federal gasoline tax cut. The US uses for transportation about 10% of all of the world’s crude oil. So, if we cut taxes and our demand goes up a little bit, that could have a noticeable effect on world oil prices. Still, I think that most of the pass-through would go to consumers. Is that a good idea? In California, when this came up, I did argue that a gas tax reduction is not how we should be helping consumers in need. First of all, there are plenty of wealthy consumers who can afford the price of gasoline and the taxes. California has a lot of income inequality. And, there are plenty of poor consumers who are getting hit by rents and other rising costs and who aren’t driving that much. So, California ended up doing a rebate that’s income-based, rather than doing a gas tax holiday. I think that’s a far better approach. Of course, if you are somebody who drives a huge amount and who has to drive a big vehicle, you are still getting hurt even if you get that rebate, but I still think overall that’s a better policy.

Leo Feler: When we talk about things that the federal government can do, they considered reducing federal taxes, they released oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR), now they’ve recently announced they’re going to be doing buybacks for the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. What are your thoughts on this policy of selling oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and buying oil back, in terms of helping stabilize the price of gasoline?

Severin Borenstein: I think selling oil from the SPR is a good idea. The SPR is there to deal with geopolitical disruptions to the oil market, and I think it’s pretty easy to make the case that Russia invading Ukraine brought on a geopolitical disruption to the oil market. Even if it was primarily caused by the US and western country sanctions, it’s still a disruption. I think more generally, it’s a little harder to see what the justification for an SPR is now than it was 30 or 40 years ago.

Then, the United States was a big net importer of crude oil. Now, the United States and Canada together (and Canada is a pretty reliable partner) are a net exporter of crude oil. So, I think it’s harder to make the case that the US economy is really vulnerable to high oil prices. If anything, I would have probably argued for a bigger SPR release right now. If we’re trying to geopolitically put Russia in a more difficult position, getting those oil prices down would be very effective. The Treasury Department came out with a report a few days ago arguing that the Administration’s actions have lowered prices 20 to 40 cents a gallon. I think it’s probably closer to the low end than the high end of that range.

There’s a harder question of whether we should we be refilling the SPR. Given that the primary justification of US economic vulnerability has gone away – and certainly supply shortages have gone away – should we have an SPR? As I’ve just said, we have another use for the SPR in this case. Even though the US is not facing a continental North American shortage, it still makes sense to use the SPR as part of the economic tools to deal with Russia. So, I’m torn on that. It’s a hard case to make. The SPR actually grew out of the 1970s, the Arab Oil Embargo, and the long gas lines we faced back then.

The long gas lines were not caused by the Arab Oil Embargo, they were caused by our attempts to regulate gasoline prices and keep them down even as oil prices were going up, and that’s what caused shortages. In 1991, during the first Gulf War, crude oil prices went way up, and you don’t hear about the long gas lines of 1991 because there weren’t any. We deregulated gas prices, and gas prices were allowed to adjust, but people still got gasoline. As I always say when I’m asked about regulating gas prices, as much as people hate high gas prices, they really hate sitting in line for an hour to even be able to buy gasoline.

Leo Feler: What are your thoughts on using future repurchase agreements for the SPR as a way of stimulating more oil production in the US and trying to create a floor for what crude oil prices producers might receive in the future?

Severin Borenstein: I think that’s really not going to be very effective. It’s one thing to release a million barrels a day over a six-month period. It’s another to say we’re gradually, over the next many years, going to repurchase crude oil. Over that time frame, producers can find markets for their product. I don’t think it’s going to have a big effect on stimulating oil production, and I don’t think we should be doing it for that reason. It’s just going to be a small bit of the market over many years. I think there’s a bigger issue. If we actually make progress on decarbonizing the economy, and if we make progress on decarbonizing transportation worldwide, the price of oil is going to crash. If you just do the economics, it’s pretty clear that if we took about one-third of the crude oil demand out (and we’re going to have to do a lot more than that) we’re not going to see a constraint in the oil market, and Saudi Arabia’s power in the oil market disappears. When we had drops in crude oil demand, and the pandemic was obviously the most extreme case, that’s what happened. The real problem is going to be, crude oil is going to drop, I would guess to $20 or so per barrel. At that point, our problem is going to be how we keep the economics of EVs working when gasoline worldwide becomes super cheap. We need more than just US policy to push forward with decarbonizing. We also need policy in developing countries to do the same. But developing countries can argue, “We’re not the ones who put most of that CO2 in the atmosphere, and we’re still a poor country. We need whatever is cheapest to keep growing our economy, and crude oil is super cheap.” I think that’s the real challenge, and trying to stimulate more production over the long run is probably not good policy.

Leo Feler: Severin, thanks for joining us. This was a great conversation, and I appreciate the insights.