Websites peddle unnamed hotels and even cities; would you pay to omit one from the list?

Eurowings, the German low-cost airline, offers leisure travelers a sweet deal. Fly to many of its popular European destinations for as low as 33 euros (about $38). The only catch: Eurowings decides where you end up.

It works like this: Choose a starting point among Eurowings’ German or Austrian cities and select from a handful of thematic categories — party, culture, metropolis and others. (The options vary depending on the departure location.) Then pick the travel dates. Once paid, Eurowings reveals your destination.

The offering, called blind booking, is a form of “opaque pricing,” in which consumers get large discounts but don’t know exactly what they will receive. It’s a way for travel companies, retailers and others to dispose of inventory with a sell-by date (end-of-season fashion, unfilled airline seats or vacant hotel rooms) without resorting to clearance sales.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

The practice has advantages for those on both sides of the transaction, but it comes with drawbacks. Customers can leave dissatisfied if they end up with a purchase they don’t like. Sellers remain in the dark about customers’ true preferences.

A working paper by Qing Li of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, UCLA Anderson’s Christopher Tang, and He Xu of Huazhong University of Science and Technology considers the strategies sellers might use to maximize their profits from opaque sales while keeping customers satisfied. The best approach: Charge buyers an added fee to eliminate their least-wanted option.

Discounts, markdowns and fire sales are regularly used to dispose of leftover inventory and unsold capacity. The problem is that they’re so common that many customers come to expect price cuts and delay making a purchase until a product goes on sale.

Opaque pricing is a way to appeal to a group of bargain hunters — those who don’t have a strong preference for a particular product — without cannibalizing regularly priced goods. The practice was made popular in the dot-com era by Priceline and Hotwire, discount travel sites that resold airline tickets and hotel rooms while keeping the exact details secret until the sale was completed. With Priceline, for instance, travelers looking for hotel deals choose their arrival and departure dates, the general location and whether they prefer two-, three- or four-star properties. They name the price they’ll pay and accept Priceline’s choice of hotel.

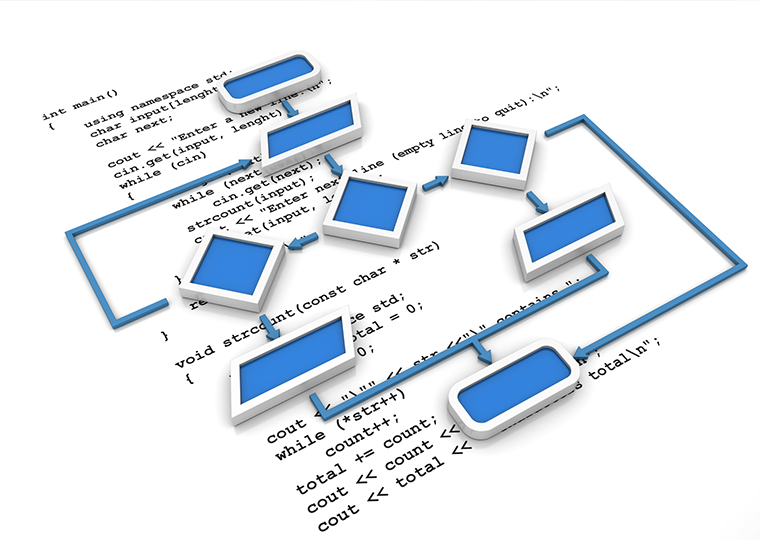

In their paper, the authors consider a problem with opaque pricing called the “double-blind” effect. Not only are customers ignorant of what exactly they’re paying for, but sellers also don’t know whether the buyer might be willing to pay more for one option over another, hurting revenue.

Tang and his co-authors explore ways to make these deals more transparent. The seller could disclose inventory levels of the different options, which would indicate to the buyer the likelihood of receiving her preferred choice. Sellers could collect more information about customers’ preferences, which would make it possible to set higher prices for more desirable options. Pack Up + Go, which offers blind selling of hotel-and-air packages, surveys customers about past travel, hobbies and interests and their upcoming trips before making a sale.

The third alternative: Buyers could pay a fee that lets them discard a possible option. Eurowings does this. For 5 euros, blind-booking travelers can remove a destination from the list of possibilities.

Using an analytical model that considers opaque pricing for two distinct products, the authors conclude that giving buyers more information about inventories delivers no short-term economic benefit. Neither does asking customers about their product preferences.

If a seller shares inventory information, buyers who value one choice over the other might be willing to pay more, but the seller is limited in how much it can raise prices or risk losing those customers who won’t pay the higher price. So, the model suggests, revenues are no higher than if inventory levels remain hidden.

A similar difficulty occurs when a seller solicits customers’ product preference. Buyers assume that they are likelier to get their desired choice, and therefore they place a higher value on the opaque products. But the seller can’t take advantage by charging higher prices, since only some buyers would be willing to pay more.

In both cases, the model suggests, the firm charges less than what some customers would be willing to pay. That makes the consumer happy, and can lead to repeat purchases, positive reviews and long-term benefits. But it doesn’t give the biggest boost to company profits.

Charging a fee to eliminate an undesired destination or product, the model suggests, boosts revenues by letting the seller charge customers with at least some product preference more. The Eurowings approach, which charges the same fee regardless of the destination that is eliminated, works. But, the model suggests, an even more profitable approach would be to charge different fees for different locations, especially when some destinations are considerably more desirable than others — charging more to strike, say, Dresden as an option for a shopping trip than you’d pay to eliminate London.

Featured Faculty

-

Christopher Tang

UCLA Distinguished Professor; Edward W. Carter Chair in Business Administration; Senior Associate Dean, Global Initiatives; Faculty Director, Center for Global Management

About the Research

Li, Q., Tang, C., & Xu, H. (2019). Mitigating the double-blind effect in opaque selling: Inventory information, customer preferences, and options pricing.