Reviews that explicitly talk about objective quality assessments are well received

The wisdom of crowds that is the customer review has become a ubiquitous factor in online shopping. From checking out TripAdvisor reviews, sorting an Amazon search by customer rating or limiting our dining choices to restaurants with at least four stars on Yelp, we’re seemingly sold on the opinions of strangers.

So, businesses feverishly recruit consumers as unpaid marketers. When was the last time you weren’t asked to leave a review or share a purchase to your social media nearest and dearest?

Yet this explosion in consumer reviews does not translate to blanket effectiveness.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

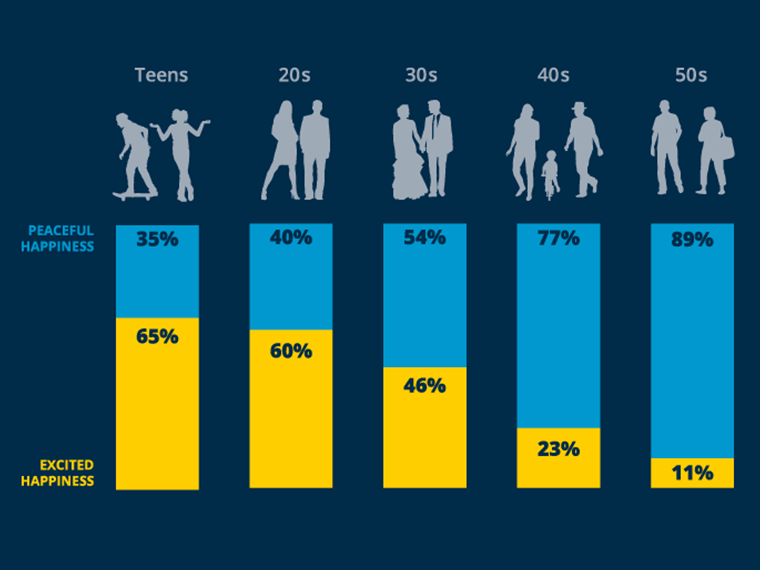

UCLA Anderson’s Hengchen Dai and Cassie Mogilner Holmes and the University of Toronto’s Cindy Chan find that we consumers are indeed influenced by customer reviews when shopping for a product whose attributes can be objectively assessed. But when contemplating something that is an experience, we’re relatively less interested in others’ opinions.

For instance, we’re likelier to consider customer reviews when shopping for a hot tub for the backyard than if we’re searching for a hot springs resort for a much-needed getaway. The material good lends itself to objective analysis: quality of material, whether it works well, wear-and-tear, etc. Rating an experience is a less objective matter and the opinion of strangers holds less allure.

“Even though people are open to being told what to have, they prove more reluctant to being told what to do,” the researchers write.

Dai, Holmes and Chan analyzed more than 6.5 million Amazon reviews and ran four lab tests to tease out the effectiveness of reviews for material items you can keep, and experiential items that are about “something you can do.”

Their Amazon analysis focused on the likelihood that a review for a given item was rated helpful by other shoppers on Amazon. The 26 product categories that these 6.5 million reviews covered were rated on a scale of 1 (purely material) to 9 (purely experiential) by 100 survey participants.

On average, 69 percent of all reviews were rated helpful. The more material a product, the likelier consumers would rate a review helpful. Shoes were deemed the most material category with a score of 2.57 on the 1–9 scale, and 77 percent of shoe reviews were tagged as helpful. Videos for streaming were deemed most experiential with an average score of 7.12, and 60 percent of reviews were rated helpful.

Given that analysis can’t account for all the consumers who didn’t bother to rate a review, the researchers ran some lab experiments to further investigate the role reviews play for different purchases.

A group of 203 participants was sorted into a shopping exercise for either cooking classes (experience) or an espresso machine (material). Participants in each section had two items to choose from. They were given a description of each item, along with one review for each. One item received a glowing five-star review, and another received a “meh” three-star review.

The positive review was more important for the espresso machine shoppers, as nearly 80 percent chose the machine with the five-star review. But it had less sway for the cooking class shoppers, who chose the five-star course 66 percent of the time.

Given that many purchases straddle the line between material and experiential (a bed is material, a good night’s sleep is very much the desired experience), the researchers ran a side experiment that primed participants to view such a purchase as either material or experiential. They came up with the same results: When focused on the material attributes of a sleeping bag, participants were more swayed by reviews than when prompted to focus on the sleep experience.

To apply some real-world input, another experiment tasked 301 participants with shopping online for something fun or enjoyable. Participants were primed to focus on either a material or experiential item that they were planning to buy next year and were asked to find reviews for that item. Then participants rated the reviews on a 1 (not very)-to-7 (very) scale for whether they were helpful and useful, and the extent to which the participant was likely to rely on the reviews. Those three elements were rolled up into one reliability score.

The 5.8 average review score for reviews of material items was higher than the rating of reviews for experiences (5.4). Participants were also asked to rate the extent to which assessing an item boiled down to its objective quality. Shoppers for material items perceived that reviews were more about objective quality assessments than the experiential shoppers.

The researchers then turned to the question of the extent to which a negative review impacts choice. More than 200 participants were sorted into two ice-cream shopping groups: some had to choose between buying ice cream at one of two ice cream shops (experience), and the others were asked to choose between two ice cream makers (material).

Participants were first asked to make their purchase choice, and were then presented with a negative review about their choice and the chance to change their minds. They were also asked to rate the objectivity of the review they read.

The material group on average rated the objective quality of reviews higher than the experiential group (5.0 vs. 4.1), and the review seems to have had more sway: More than half of the ice-cream maker group changed their minds on which product to buy, compared to 35 percent of the experiential buyers.

In their final experiment, the researchers landed on a finding that should be of interest to marketing departments with experiential products: Playing up reviews that explicitly talk about objective quality assessments moves the needle.

More than 750 participants were put through the ice cream shop versus ice cream maker exercise and were shown a negative review after making a choice. In each group, half of participants were shown a review that included objective quality assessments. Then participants rated on a 1–7 scale their likelihood of changing their minds.

The control groups in which reviews did not contain objective quality assessments followed the trend from the earlier experiments: Experiential purchasers were less interested in relying on consumer reviews. But when reviews were doctored to explicitly call out objective quality assessments, experiential buyers became nearly as reliant on consumer reviews, and both groups were likelier to change their minds.

“People believe assessments of experiential purchases are less based on objective quality than assessments of material purchases, and this belief undermines people’s willingness to rely on other consumers’ reviews for their experiential purchase decisions,” write Dai, Chan and Holmes. But as their research teases out, playing up good experiential reviews that include some objective assessments can increase a review’s effectiveness in influencing purchase behavior.

Featured Faculty

-

Hengchen Dai

Associate Professor of Management and Organizations and Behavioral Decision Making

-

Cassie Mogilner Holmes

Professor of Marketing and Behavioral Decision Making; Donnalisa ’86 and Bill Barnum Endowed Term Chair in Management

About the Research

Dai, H., Chan, C., & Mogilner Holmes, C. (2018). People rely less on consumer reviews for experiential than material purchases.