June 2021

June 2021

Streets of Gold

Economic Update: Inflation Worries and Supply Constraints, with Leo Feler, Senior Economist, UCLA Anderson Forecast

- In our June 2021 Forecast, we said we expected the Federal Reserve would begin tapering asset purchases by the end of 2021 or beginning of 2022 and might increase rates starting at the end of 2022 or beginning of 2023. We stated that this timeline would be consistent with the Federal Reserve’s aims of full employment and stable prices.

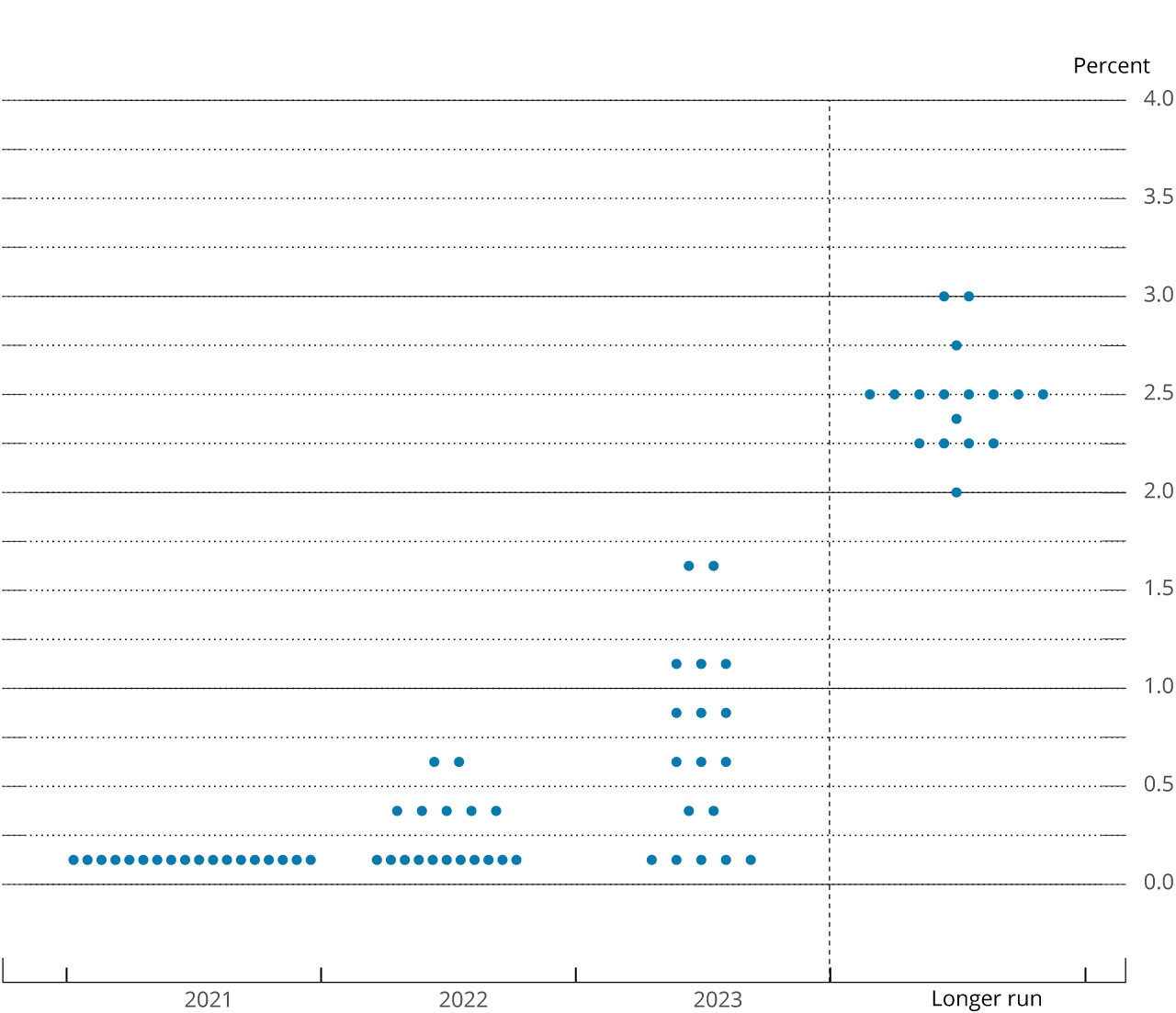

- Indeed, the Federal Reserve’s Summary of Economic Projections, released on June 16, shows that FOMC participants’ assessment of appropriate monetary policy includes two rate increases in 2023, with the median Federal Funds Rate in the range of 0.50%-0.75%, from 0.00%-0.25% currently (see Figure 1). In its prior Summary of Economic Projections, from March 17, the median participants’ assessment was of a Federal Funds Rate in the range of 0.00%-0.25% in 2023, in other words, there would be no rate increases through the end of 2023.

- In our June 2021 Forecast, we said we expected PCE inflation of 2.7% for 2021 and that our forecast was for 2.1% PCE inflation for 2023, with upside risk to this forecast. Our forecast for 2021 is higher than the Federal Reserve’s, which has a median projection of 2.4%. For 2023, our forecast is in line with the Federal Reserve’s median projection.

- The most recent CPI inflation reading, for May 2021, came in slightly higher than we expected, at 5.0% year-over-year. It’s important to keep in mind that May 2020 was the trough of the CPI, with consumer prices having declined in March, April, and May of 2020. When we control for “base effects” by smoothing across the 15 months since February 2020 and exclude the price declines that occurred through March–May 2020, the rate of CPI inflation was 3%. Core inflation, controlling for base effects was 2.6%, half of which was driven by cars: used cars, new cars, and car rentals. We continue to expect that this increase in inflation is transitory and that inflation will stabilize in the coming months as supply constraints ease. Used car prices have already started to come down from their peak.

- Job openings continue to increase, at 9.3 million in April versus 8.3 million in March. Meanwhile, the economy added 559,000 jobs in May. Over the past three months, the economy has added approximately 540,000 jobs per month (we were expecting 740,000 jobs added per month, on average, for April–June). The headline unemployment rate fell to 5.8% in May. We expect faster jobs growth in the coming months as the pandemic wanes, expanded unemployment benefits expire, and as schools fully reopen in the fall.

Figure 1: FOMC participants' assessments of appropriate monetary policy: Midpoint of target range for the Federal Funds Rate (each dot represents one FOMC participants' assessment)

Source: Federal Reserve, Summary of Economic Projections, June 16, 2021, available at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20210616.pdf.

A Conversation with Leo Feler and Leah Boustan

This month, the UCLA Anderson Forecast features a conversation with Leah Boustan, Professor of Economics at Princeton University. Professor Boustan does research on economic history and labor economics. We discuss her forthcoming book, co-authored with Ran Abramitzky, called Streets of Gold: Discovering the Truth and Busting the Myths of American Immigration. Following is a condensed transcript of the conversation; full audio and video are available at the links above.

Leo Feler (LF): Professor Boustan, you include the following quote from an Italian immigrant at the very beginning of your book: “I came to America because I heard the streets were paved with gold. When I got here, I found out three things: First, the streets weren’t paved with gold. Second, they weren’t paved at all. And third, I was expected to pave them.” Let’s start with the concept of streets of gold – is it a myth? What is life like for immigrants arriving to the US?

Leah Boustan (LB): In one way, we find that the concept of streets of gold is actually very true, and has been true both in the past and today. Moving to the United States allows immigrants to increase their own income sometimes two or three-fold compared to what they would have earned had they not immigrated. In that way, you think “yes, the streets in the United States do offer gold for immigrant arrivals.” But in another way, if the idea is that moving to the United States allows immigrants to move up the economic ladder here very quickly, we find that this is not so true, either during the past or today. So this idea of “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” or “rags to riches” was not as true as we might think 100 years ago with European immigrants, and it’s also not true today. It does take immigrants time, when they get to the US, to move up the ladder here.

LF: You mention that the benefits of immigration often accrue not really to the first generation that immigrates, but to the second generation, the children of these immigrants. You mention that the children of immigrants are much more upwardly mobile than their parents and even more upwardly mobile than the children of US-born residents who are raised in families with similar incomes. Why is that? Why do the children of immigrants do well, and why do they often do better than the children of US-born residents?

LB: That’s exactly right. We were able to look at children of immigrant parents and children of US-born parents 100 years ago and today. We see the children as adults, working in the labor market, and we’re able to trace them back to their childhood homes. Both 100 years ago and today, the children of immigrants earn more than the children of US-born parents. If you ask people, “Why are the children of immigrants doing better than the children of US-born parents?,” they’ll say it has something to do with immigrant values – immigrants work harder, they instill a concern for education in their kids. That was our first guess too, that maybe it has something to do with education. What we found, though, is that what matters more is geography. Immigrants come to the US and settle in labor markets that offer opportunities for upward mobility. This is especially true in the past. Think about the US South 100 years ago. It was primarily agricultural, there were a lot of cotton farms, and immigrants avoided moving to the US South. Instead, they were living in the North and West. Within the North and West they were particularly living in booming cities. So, we find if we compare immigrants to their next-door neighbor – someone else who’s living in the same place – actually their kids do very similarly. The pattern that we see nationwide is coming from the fact that immigrants are choosing to live in up-and-coming, upwardly mobile cities. So, coming back to the idea of immigrant values, is this a value? Well, it might not be the same as hard work or concern for education, but there is something about the immigrant experience that makes sense of this pattern. Immigrants already chose to leave home and break ties with family back in their home country in order to move to the US and seek opportunity here. So, once you get to the US, you have a set of possible locations to choose from, and it makes sense that immigrants would look for the place that offers the most opportunity. In contrast, people who are born in the US are already born into a particular state, into a particular city. They’re living close to home. Some of them will move out in order to seek other opportunities, but many won’t.

LF: There’s been some discussion of “heartland visas,” which are visas for immigrants conditional on them going to specific cities. What are your thoughts on allowing immigration but conditional on it being only to certain areas of the US?

LB: What we found is that one of the ways immigrants are so successful is that they do have a choice of geographic location. Immigrants will settle in dynamic cities like San Francisco or New York, or burgeoning places like North Carolina because there are great opportunities there. So, if immigrants arrive and are only allowed to settle in some of the slower-growing places, in cities like Detroit or Buffalo, then we would not expect to see immigrants doing quite as well as we see immigrants doing today. At the same time, there are many people lining up all around the world to come to the US. Simply by moving to the US, a more productive economy, immigrants can take their own knowledge and their own labor and make more out of it – they can earn more here than at home. So, if you gave someone the choice, “Do you want to settle in Buffalo, or do you want to stay home?,” many immigrants would still choose Buffalo. They’d say, “I’m happy to come. I know I won’t do as well as if I had my choice of labor markets, but I’m willing to come even if I have to settle only in a subset of places.” I think we would find people signing up for those heartland visas, and simply by adding population to areas that had been declining, we might see some economic benefits.

LF: How do immigrants coming today differ from immigrants coming from Europe 50 to 100 years ago, both in terms of education and the capital they’re bringing in? Is there a difference that leads to a different starting point that affects their success going forward?

LB: What’s fascinating is that there are actually huge differences between immigrants to the US, now and in the past, but there are not large differences in their outcomes. And so even though we’re attracting a very different set of immigrants today, those immigrants are achieving the same degree of success as immigrants in the past. In the past, almost all of our immigrants were coming from Europe. Europeans made up around 90% of our immigrant stock, and the other 10% were from Canada. Today, immigrants are coming from all over the world. Europe makes up only around 10% of our immigrant stock. Many immigrants are from Mexico, from other parts of Latin America, and from Asia. In terms of background, skills, once again, are quite different. Europe and the United States were relatively comparable in the past. There were some parts of Europe that were actually ahead of the US in the past, places like the UK, and other parts that were behind in terms of GDP per capita, but not so far behind. Today, we’re drawing immigrants from parts of the developing world where the GDP per capita of those countries is substantially below the US. So, the opportunities that people have to receive an education are substantially lower. As a result, we have many immigrants today that start out with very low levels of education relative to the US-born population. Another really interesting thing is that even though immigrants today come from the developing world, many of them are coming from the very top of their home country distribution, in terms of wealth and education. We have immigrants, for example, from Nigeria – 60% of whom have a college degree. If you look at the Nigerian population, only 5% have a college degree. What we’re ending up with today are immigrants we think of as “bi-modal” in education. Some are very low-education, and some are very high-education. They’re coming from both ends of the education distribution. I’ve mentioned now several differences between the past and present which might lead you to think, “Well, immigrants today are going to have a very different path. Maybe immigrants did well in the past, maybe they moved up the economic ladder. But, immigrants today are coming from very different places, and very different backgrounds, so they may not succeed to the same degree.” And what was really fascinating about our work is that despite these differences in background, we’re seeing very similar patterns of upward mobility.

LF: If it’s not necessarily the nature of immigrants themselves, is it the nature of our society? You mention that immigrants with different backgrounds come in, they tend to do very well here. Has our society changed in a way that has helped them become more or less successful over time? And by that, I mean we used to be a very manufacturing-heavy society, with much more manual and low-education labor. Now we’re a much more service-oriented, high-education society. Has that changed how immigrants are able to advance? Has it led to inequality among immigrants compared to the past?

LB: In terms of income levels, we definitely see inequality between immigrants today. Some immigrants, as I mentioned, are highly educated, and they earn just as much, if not more, than the US-born. Some immigrants arrive with very little education, and they earn a lot less. They’re filling in the bottom 10%-20% of the income distribution. So, we have a lot of inequality within immigrants today. But immigrants at the bottom of the income distribution are experiencing income growth. Even if they arrive and earn very little, they are moving up within their own lifetimes, and their kids are moving up in their lifetimes. The way we see it is that background is not destiny. It does give you a sense of where immigrants will be in the first few years of their time in the US, but it doesn’t tell you where their kids will be in the next generation.

LF: How does documentation status help immigrants? You talk about how immigrants come to the US, then it might be slow-and-steady for the first generation, and then their kids are better off. But the challenges associated with documentation status have grown over time. Has this created some kind of bifurcation where documented immigrants do well while undocumented immigrants struggle?

LB: What’s interesting is the generational piece of this. Most children of undocumented immigrants are US citizens, around 75% to 80%, which means that the struggles their parents face, the struggles of the first generation, will not be their own struggles. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons we’re finding dramatic rates of upward mobility for the second generation. If your parents are undocumented and they have certain talents but aren’t able to use those talents in the labor market, they’re going to end up taking jobs that don’t require documentation, maybe cleaning houses, doing something off the books. But if their children don’t face these barriers, when these children go to the labor market, they’re going to see a dramatic rise in incomes relative to their parents. We’re lucky that documentation status is not an inherited part of someone’s identity, otherwise we’d be facing pretty severe economic barriers for immigrants and their children. Now there’s still the question about the other 20% to 25% of kids of undocumented immigrants, who themselves are undocumented. What people find is that up through high school, these kids do well. They have a right to elementary and secondary education, and their documentation status doesn’t come up in the classroom. It’s when these kids realize going forward that it’s going to be hard to find a job or hard to go to college, that’s when a lot of hopelessness comes in. We have a policy-lever we can pull, which at the moment is the DACA program (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), and it’s via executive order. It would be helpful for the economy if we enshrine that in legislation, which was the idea behind the DREAM Act. I think at this point, because we have DACA and because it held through the Trump administration, it’s been tested, and I think we’re okay. We have about 75% of kids who are themselves citizens, and the other 25% who have DACA, but more could definitely be done here to lower barriers.

LF: What about the impact on US citizens? There’s a lot of discussion that immigrants are coming and taking US jobs. But you find something interesting in your paper, that it isn’t a zero-sum game, where immigrants come and out-compete US labor. Can you talk about the effect that immigration has on the US labor market for existing US residents and existing US citizens?

LB: There has been a generation of work on this topic, with modern data and modern examples. One of the things we do is we go back to a historical period which gives us some insight on this question. And that is the period of the 1920s. Up through 1921 or so, immigration to the United States from Europe was essentially unrestricted, to the point where you didn’t even need a visa or a passport for entry. That whole regime changed in the 1920s, with a set of very restrictive immigration quotas, actually even more restrictive than what we have today in terms of the numbers that were allowed in. We thought this would be a good opportunity for us to think about what happens if immigration were to be cut off like that today. What we find is that firms are incredibly adaptive to the loss of labor. It’s not like immigrant workers and US-born workers are the only two options. There are also other places that firms can look for workers, and there’s also the possibility of replacing workers with machines or offshoring work. We find slightly different sources of adaptation in different parts of the country. In the manufacturing sector, factories needed workers, and so when Europeans stopped coming in, firms started attracting workers from other parts of the US, who were moving as internal migrants. In rural areas, farmers had been reliant on immigrants for farm labor, and once immigration was cut off, they switched over to tractors and other types of machines. Certainly, there is a direct analogy here between the rural areas and shifting over to tractors, and automation today. There are many tasks that could be done by human labor or could be done by machines.

LF: That brings us to the situation we’re in today, where many firms are facing labor shortages despite high rates of unemployment. We’re hearing firms say how difficult it is to hire workers. We’re seeing baby boomers retiring. We’re seeing low birth rates. Our population is likely to shrink over time without immigration. What are your thoughts about what the US needs in terms of immigration policy going forward? What would be an optimal design for immigration policy to sustain US growth for the next decade?

LB: Some people point to the Canadian immigration system, for example, that gives immigrants points for desired traits. If you speak English, you get a point. If you graduated from college, you get a point, and so on. They select immigrants who are above a certain threshold. I think that type of system is problematic because what we need in our workforce going forward might not be things that we can write down on paper and say, “well, we need college grads.” What we might need, going forward, are a lot of people who are eager to work in eldercare or childcare. Those kinds of immigrants may not show up very well on a point score, under the Canadian system, but that might be precisely the immigrants we need. And I know that advocates of point systems say, “well, we can re-evaluate our needs as we go, and if we need immigrants of a certain type – like if we need eldercare – we’ll prioritize that down the line.” But I think immigrants are smart enough to know, “my skills are needed in the US. This is how much I might earn if I move there.” And, immigrants are responsive to the economic opportunities we offer. I think in some ways, we have a system that works just fine, and the question is, do we want to tinker at the margin to increase the quota cap we have now? We set a quota of a little under 700,000 immigrants a year, and then there are additional immigrants who come in that are above the quota cap, because they are a spouse or child of a current citizen or green-card holder. So, we get around 1 million immigrants a year. What if we increased it a bit more than that? What if it was an additional 100,000 or 200,000? How many additional immigrants would we need to fill some of the labor market gaps you mentioned, in terms of the aging workforce? I’ve seen the numbers, and it’s really not that much more. Somewhere between 200,000 to 300,000 additional immigrants – so a 20%-30% increase would go a long way given the declines we have in the birth rate, the aging population, and the slowdowns we’ve had in immigration recently.