March 2022

March 2022

Is the Housing Boom About to Go Bust?

Leo Feler, Senior Economist, UCLA Anderson Forecast

Stuart Gabriel, Director, UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate

Is the Housing Boom About to Go Bust?

- “Inflation is much too high.” This was the conclusion of Fed Chair Jay Powell’s speech on Restoring Price Stability at the National Association of Business Economics Conference on March 21, 2022.

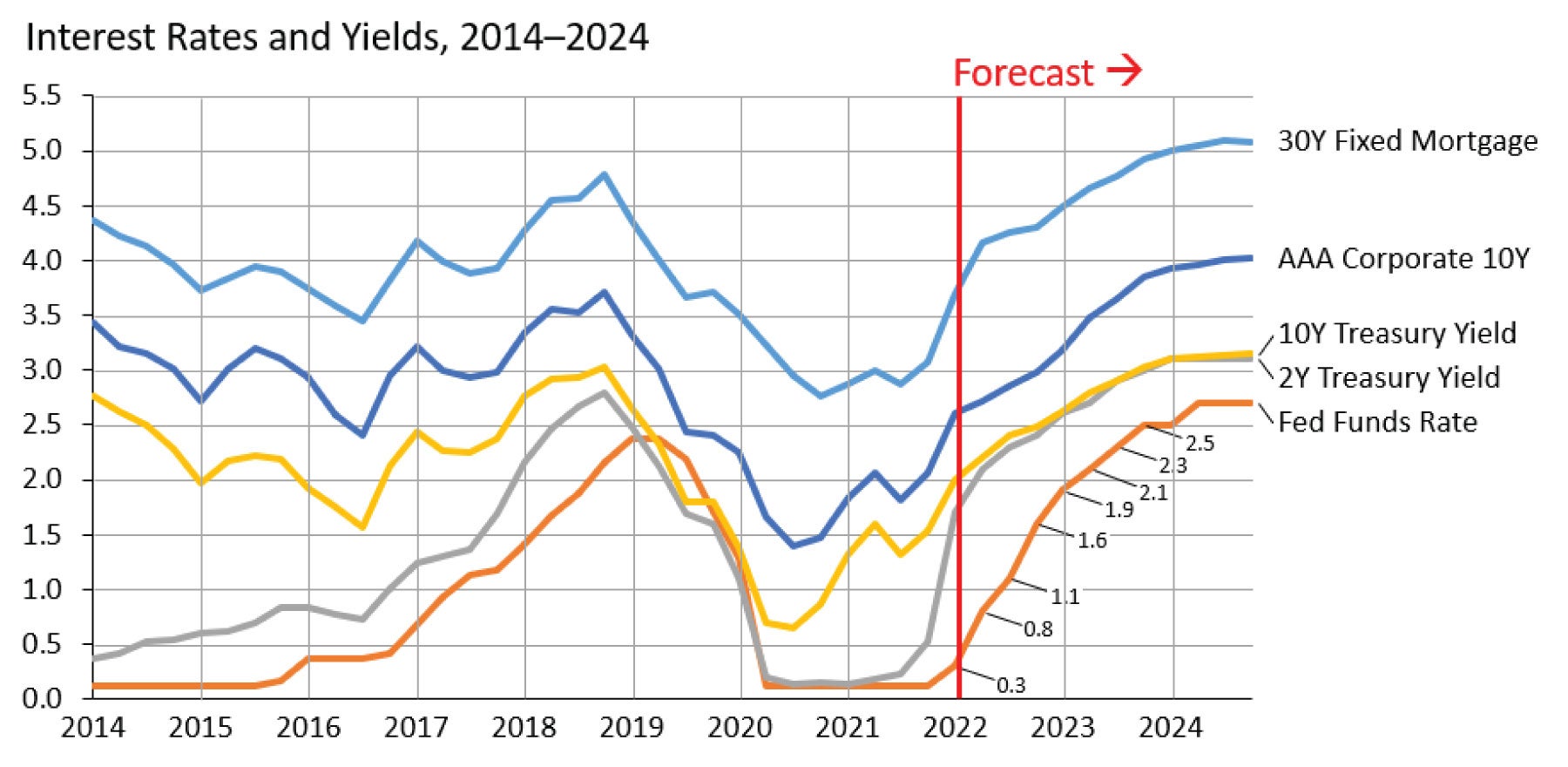

- We are forecasting that the Fed Reserve’s benchmark rate, the Fed Funds Rate, will end the year around 1.75%-2.0% (see Exhibit 1). That means a total of 6-8 interest rate hikes this year, with some of those hikes potentially being 50 bps.

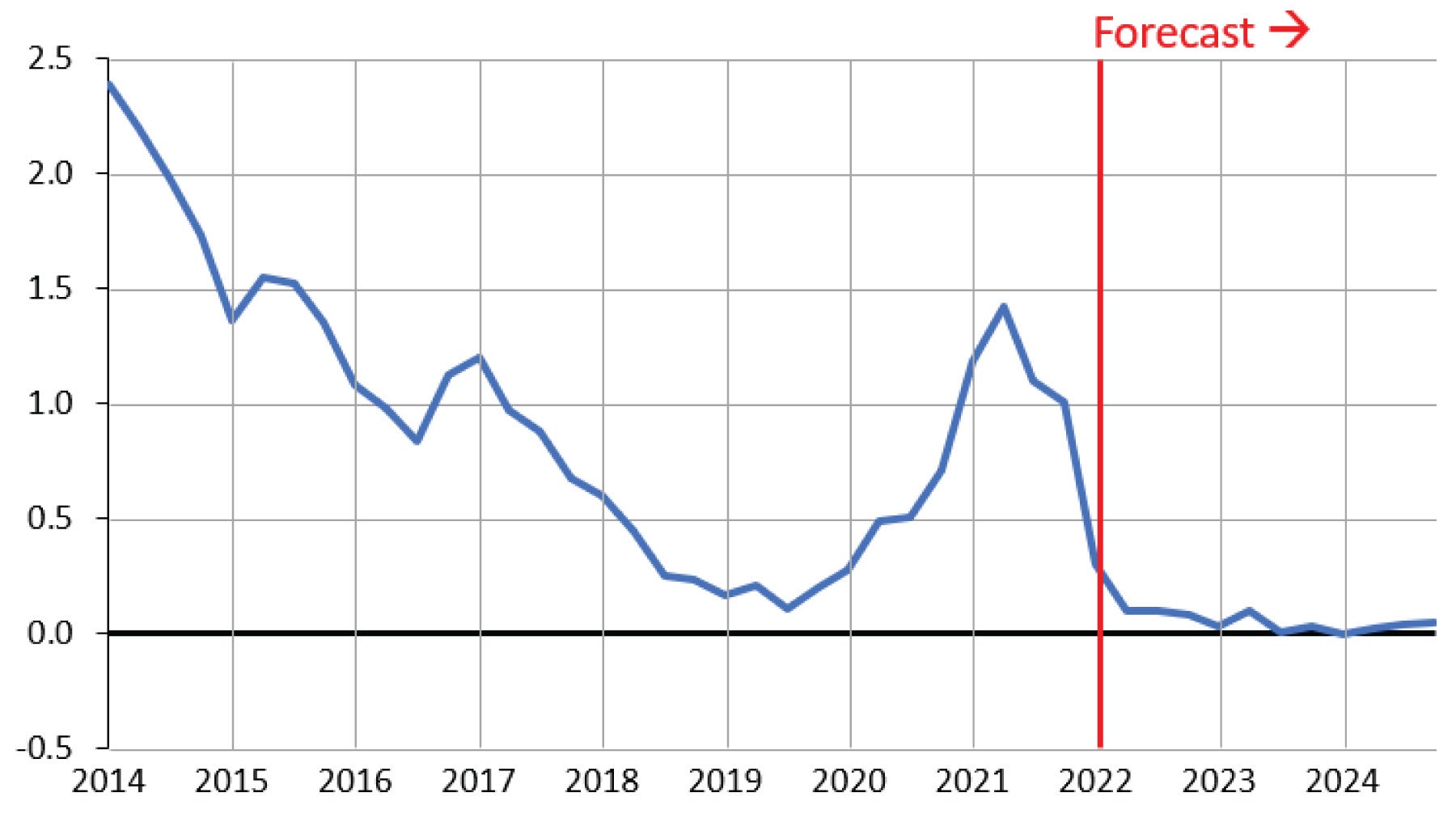

- Unless long-term rates also increase by as much, and right now long-term rates have also been increasing fairly rapidly, we may see a sustained inversion of the yield curve, which has been a reliable predictor of recessions. Right now, we’re not forecasting a sustained inversion of the yield curve, but we do expect it to flatten considerably and remain fairly flat throughout the year (see Exhibit 2). A flat yield curve means financial intermediation becomes more conservative. Banks lend long-term and borrow short-term. If the difference between short and long-term rates is minimal or negative, that makes it less likely that lenders will be willing to take on riskier investments.

- Does this mean we’ll have a recession? There is now considerably more uncertainty to our forecast, and we think a recession during the next 12-18 months has become more likely, but it’s still not likely given increased defense spending, record consumption, a booming housing market, and recovering auto production. If we do have a recession, we think it will be because the Fed tightens too quickly and businesses cut back on investment.

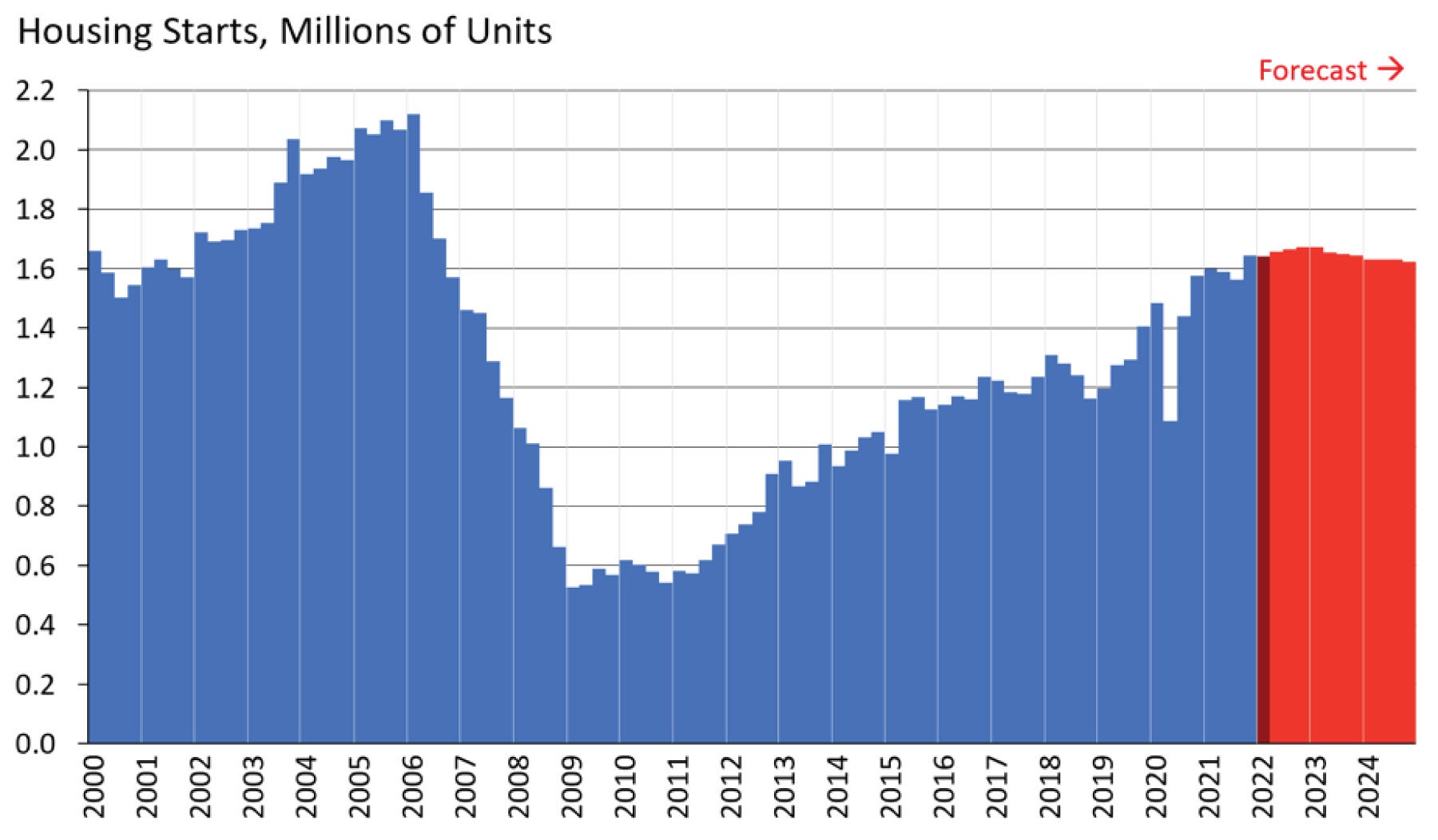

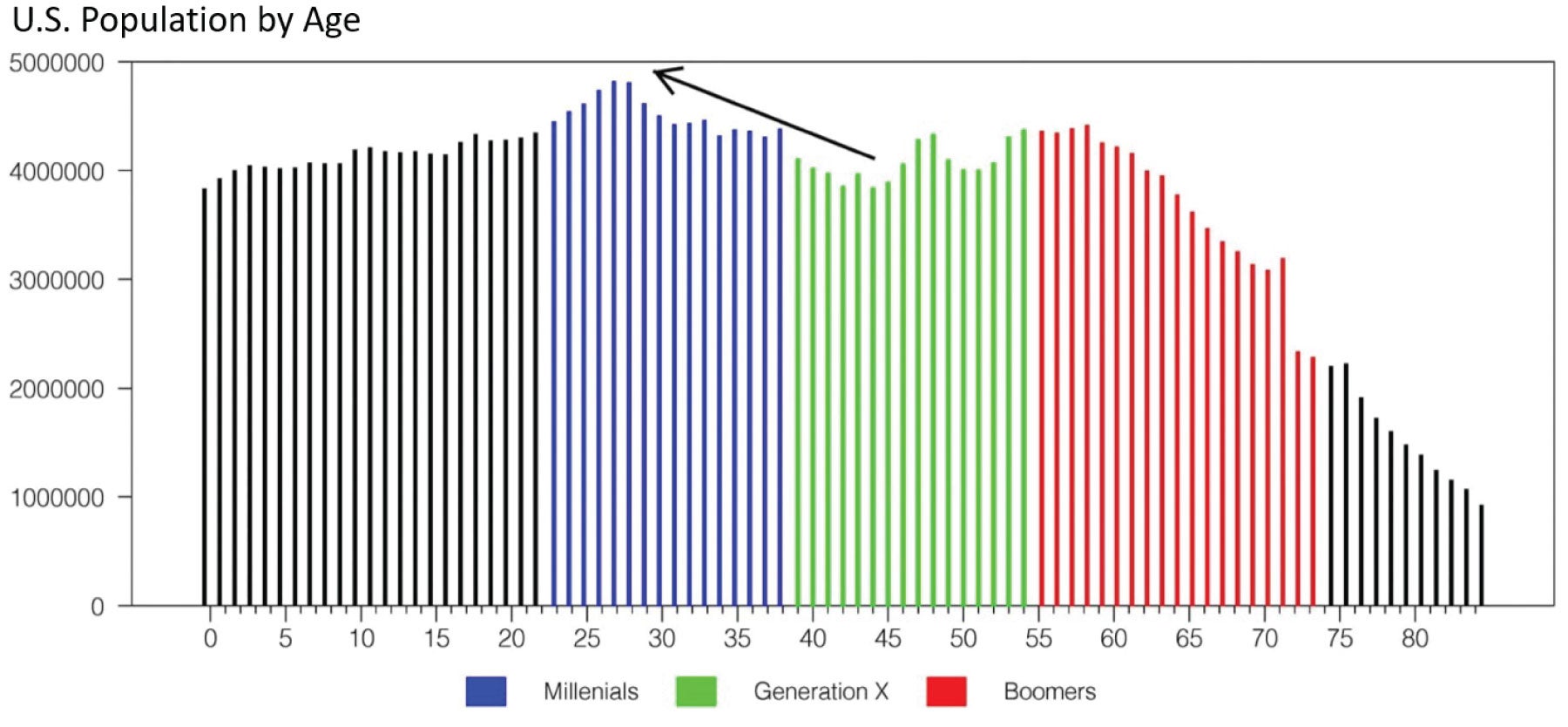

- We are not as concerned about a housing bust, and that’s because of the combination of demographics and a decade of underbuilding. Throughout the 2010s, we underbuilt housing (see Exhibit 3), and now we’re facing a wave of aging millennials who are starting families and looking to buy homes (see Exhibit 4). However, if we begin to see unemployment ratchet up as the Fed tightens monetary policy, then we might get a decline in housing prices, rather than just a slowing of the rate of home price appreciation that we’re currently expecting.

Exhibit 1: Forecast of 6-8 interest rate hikes this year, taking the Fed Funds Rate to 1.75%-2.0% by the end of the year

Exhibit 2: Spread between 2Y and 10Y Treasury Yields

Exhibit 3: A Decade of Underbuilding

Note: Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rates

Exhibit 4: The Millennial wave will continue to fuel housing demand

A Conversation on Housing Markets

with Leo Feler and Stuart Gabriel

Director, UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate

This month, our podcast features a conversation with Stuart Gabriel, UCLA Anderson Distinguished Professor of Finance, Arden Realty Chair, and Director of the UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate. We discuss housing prices, interest rates, and housing supply. Below is an edited transcript of the conversation.

Leo Feler: We’ve seen home prices increase very rapidly during the pandemic, and now we’re seeing rents increase very rapidly. What’s driving these increases and are they sustainable?

Stuart Gabriel: We don’t believe the increases are sustainable since they’ve been so sharp, and it would be surprising if they were sustainable. But that doesn’t mean that house prices are either going to stop increasing or fall radically. The model forecast is for even double-digit rates of house price increase in the current calendar year. That might suggest some cooling, but not a lot. We’ll see what the events of the year bring with respect to Fed timing, geopolitical events and all the rest. But that notwithstanding, there were fundamental factors that drove house prices up, and those fundamental factors, in some respects, are still present.

Let me just say a word as to what those factors may be. First, as it’s evident to all, we’ve had near record-low interest rates and mortgage interest rates. Housing credit has been readily available, and it’s been available at bargain prices. That’s certainly been a factor that’s fueled the demand for housing.

This demand for housing has been fueled in a context of inadequate supply, in a context of inadequate production, and in a context of high levels of local regulation of housing supply. All of those elements are changing. But getting back to housing demand in the context of inadequate supply, we see demographic factors, we see pandemic factors, we see locational factors. With respect to demographics, we see the belated coming of age of millennials. We see very sharp increases in homeownership and home purchase on the part of millennials. They were delayed in moving into homeownership. With respect to the pandemic, we saw a shift from service-related spending to durable-related spending, and housing is the most durable of durables. During the pandemic, people wanted space rather than density, and we saw a substitution of housing to suburbs and to areas where there was more space and more room for work at home activities, from smaller, denser units in what were largely shut down central city areas.

We saw a shift not only in demand for housing, but in the location of demand for housing and by whom. After a number of decades of very sharp increase in demand for housing in vibrant downtowns, we saw downtowns go dark in the context of service shutdowns, in the context of the pandemic, and we’ve seen suburbs come back alive.

Leo Feler: We’re also seeing inner cities come roaring back, so we’ve seen rents increase in Manhattan, in downtown Chicago, and in downtown LA. San Francisco has been more delayed, but we’re seeing rents starting to go back up there too. Are we starting to get a shift of people back towards these central city areas?

Stuart Gabriel: Yes, but not back to the equilibrium where we were pre-pandemic. We have many factors at play. One of those factors is a work from home factor. That’s a factor that’s difficult to evaluate in terms of its longevity. There seems to be some sustainability of work from home, that employees will work at home a certain number of days of the week, if not permanently. That of course means people can literally live and work in different places. They can live in Lake Tahoe and work in the Bay Area. It also means a change in the housing characteristics required by those who work from home, in the sense that they need more space. Major home builders are factoring this into their plans for new housing construction. It is also part of the demand for a larger suburban or exurban housing unit, potentially in an area with lower housing costs. Clearly, many households could not get to such a unit in the very expensive central areas of San Francisco, LA, or New York.

Leo Feler: Do you think we’ve seen this movement from concentrated urban areas to suburbs to exurbs play itself out? Or is there still more of this movement that’s likely to happen in the coming years?

Stuart Gabriel: With the evolution of technology, and the evolution of where and how people work, and the unevenness of house prices and housing affordability across the nation, I think there’s plenty of this yet to come. We’re seeing the emergence of all kinds of tertiary centers with respect to new popularity, we’re seeing movement across demographic groups. The Baby Boomers, people of my age, are now on the move. We’ve seen millennials come into homeownership, and they’re on the move. There’s a lot of potential to this spreading out of housing, the rise and fall of metropolitan areas, arbitrage of house prices in very expensive areas. LA is just so utterly expensive that it’s putting itself out of the market for firm locations and employment development.

Leo Feler: One of my colleagues, Jerry Nickelsburg, wrote about how LA is becoming relatively less expensive because even though house prices are so expensive in LA, they have increased so much more in places like Austin, Boise, and Fresno, so that in relative terms, LA ends up looking more attractive.

Stuart Gabriel: The question is: does that relative affordability help LA in the context of an absolute lack of affordability. Our nominal affordability is so bad that I’m not sure how much that relative gain helps us.

Leo Feler: We started seeing mortgage rates go up. They’re now about 4% for 30-year fixed rate mortgages. How do you see that affecting the housing market?

Stuart Gabriel: Well, prior to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, back in the old days so to speak, in the days of the old world order, we were expecting maybe three to four Fed rate increases this year – this would be tightening on the short end of the yield curve, coupled with other monetary policy actions that relate to the balance sheet, that would certainly work to push up the treasury yield curve at the short end of the curve, maybe be reflected in a bit of flattening of the curve, and also push up mortgage interest rates all along the curve from short rates that relate to ARMs that are priced off 1-year Treasuries or 3-year Treasuries, and to the long rates that are priced off 10-year Treasuries. In general, the expectation is that the higher housing finance costs are going to slow the housing market, they’re going to take some bite out of housing demand. So while we continue to expect an ongoing increase in house prices, the increase will be slowed by the tightening of monetary policy.

That’s the pre-Ukraine War version of the answer. The current version of the answer is more complicated. There are all sorts of economic manifestations that can affect the treasury yield curve and in turn affect mortgage interest rates. To provide some example of that, we could have more inflationary impetus in the US economy, at least in the short run, owing to the combination of factors that pertain to this war, including upward movement of oil prices, maybe some sanction-related effects. That notwithstanding, we could see some pressures for additional upward movement in rates, at least in certain parts of the yield curve. The flip side is that if things get ugly enough, and certainly they’ve gotten quite ugly recently, we anticipate and have seen some flight to quality, which means more global purchasing of US government treasury securities, which ultimately can have a damping effect on rates, particularly at the long end of the yield curve. So, one scenario is not only a flattening of the yield curve, which would be a combination of the Fed conventional policy at the short end of the yield curve, coupled with these other manifestations of markets at the long end of the yield curve. It’s possible we’ll even see an inversion of the yield curve, depending on how things go. That inversion of the yield curve is a fairly reliable indicator of a recession maybe six months down the road. To boil this down in terms of housing, we’re going to see some unevenness in mortgage interest rates along the yield curve. That means we will probably see more upward movement in ARMs that are tied to short-term treasury rates than we will see in conventional conforming rates, that are tied to a 10-year treasury rate.

Leo Feler: Are you concerned that we might be in a housing bubble? If we look at what happened to equity markets, and we look at housing markets, they’re priced assuming that the economy is going to be doing well for the next several years. We’ve started getting this turn in equity markets where there is now some skepticism that the next few years will be the boom people expected them to be. Does the same hold for housing?

Stuart Gabriel: I guess the way to answer that question is to make sure we all understand how we define bubbles. A bubble in the housing market would be a sustained upward and then downward movement in price that we could not reliably relate to what we call fundamentals. Those fundamentals might include the labor market, income, wealth, interest rates, or other things that are typical economic predictors of housing demand, of housing activity, of house prices. The point is to distinguish between the global financial crisis and the sub-prime crisis of the 2000s, and today. In the period of the 2000s, we saw a great deal of credit largesse, and what I mean by that is we saw a whole massive sector of mortgage markets open up. We call that sector the non-prime sector. That non-prime sector included sub-prime mortgages and the pooling, packaging, and securitization of those mortgages, in what we call the secondary mortgage market. Or, even the re-pooling and re-securitization in what we call derivative markets including the CDO market.

That whole apparatus resulted in massive credit largesse, upward movement in prices, and bubble-like features in the housing market, when combined with so-called animal spirits, and lots of behaviors that were somehow linked in part to the housing frenzy. We don’t see those factors at play currently. We don’t have any of the non-prime sector around anymore. All mortgages that we originate are done with old-school underwriting where credit histories are checked, employment histories are checked, and employment is verified. We have very conservative securitization markets. All of the air has gone out of that balloon. There is certainly risk in the housing market and those risks may multiply if we see shocks that are negative to the labor markets, if we see people losing jobs, if we see the economy not recover properly from the pandemic, if we see additional difficult variants of the pandemic that in turn get reflected in other shocks to the economy or other shocks to the labor market. Those are more fundamental factors, so I’m both agreeing and disagreeing with the question in the sense that I do see risk in housing markets, but those risks may come from other than bubble-like features.

Leo Feler: So maybe we think about this as a shift in the fundamentals. The fundamentals may shift very rapidly in terms of a change in the labor market, unemployment rising, or a change in peoples’ preferences in returning to work. If people discover that it’s harder to get promoted if they’re remote all the time, that might actually change locational preferences. To your point, the fundamentals so far have helped determine the rise in housing prices, which is different from the Great Recession, where there was really a departure from the fundamentals.

Stuart Gabriel: Yes, at this moment I do not expect the bottom to fall out of housing markets, far from it. There is enough fundamental interest in housing, there’s enough demographic shift, there’s enough in the way of technological workplace shift that is supportive of housing demand, and there is enough shortage and regulation of housing supply, that it would indeed be surprising to see the bottom fall out of the housing market at this moment.

Leo Feler: What are your thoughts right now on housing affordability in the US and in the LA metro area, specifically?

Stuart Gabriel: Housing affordability in coastal California is horrible and it comes from a myriad of different causes. First and foremost, we’ve had a policy in place, at least since the mid 1970’s, that has allowed local jurisdictions almost full reign with respect to whatever gets built within the boundaries of a particular area, like Pasadena or Beverly Hills, and for the most part, whoever could restrict growth, did. The policies of those jurisdictions overwhelmingly represented existing residents who wanted to maximize their own property values. What I’m saying is that local government land use regulatory constraints as it relates to housing production, when added up across jurisdictions, especially popular jurisdictions on the coast of California, has made for very significant and binding housing supply constraints.

As an example of that, the State of California has kicked Los Angeles really hard with respect to LA’s plans for incremental housing supply and told LA that if there isn’t rezoning of another quarter million homes in the LA area over the next few months, LA will be denied hundreds of millions of dollars of state funding going to affordable housing. One of the changes in the political dynamic is that the state legislature has gotten involved in the housing affordability story, and it’s pushing much harder to get local governments to approve local supply of housing. The state legislature has been absent from the conversation for decades.

Leo Feler: What are other ways to make housing more affordable, to increase the supply of housing in coastal California?

Stuart Gabriel: We’ve traditionally talked about densification of housing, and there’s a lot of new legislation that’s been passed that relates to densification that threaten the very basis of what we’ve taken to be sacred in single-family housing. So now you’re allowed to put up to four units on a single-family lot in California. That’s a new piece of state legislation. We’ve talked for decades about high-density multifamily housing along major transportation corridors. We expect that will continue. That is the traditional approach.

Let me mention a less traditional approach, and that’s to use transportation infrastructure funds and transportation infrastructure development to create access from low land-cost areas to major employment centers.

In other words, we always talk about more affordable housing in Santa Monica. Santa Monica is one of the highest land-cost areas in the country, it’s built out, there is virtually no potential for any meaningful increment to housing supply, especially affordable housing supply, in a place like Santa Monica or any of the other coastal communities. Occasionally we get a project built in one of those areas, but I view it as commensurate with pouring a glass of water into the Santa Monica Bay. That’s about how much effect it’s going to have on the availability of housing. It’s nice, we talk about it, we pat ourselves on the back, but in the end, it doesn’t solve the problem.

We need to get the private sector involved in scaling affordable housing supply and not just depend on funding coming from the state or federal government in the form of tax increments, bonds, financing, or low-income housing tax credits. To do that we have to open up lands that are relatively inexpensive. Those lands exist. They’re in places like Palmdale, Lancaster, other parts of LA County. The issue is really access. That’s where transportation infrastructure can come in. Traditionally, housing developers have leveraged public investment in transportation infrastructure. That’s a magic formula for them: put the housing tract next to the new freeway exit, and it’s golden, it’ll work. I’m encouraging that when we think about access, when we think about transportation infrastructure, we think also about opening tracts of land to housing construction where there is less regulatory constraint, where there are lower land prices, and where housing developers can get into the act of helping to address our housing supply challenge.

Leo Feler: Stuart, thank you. This has been a fascinating discussion, starting with what’s been going on with housing prices, to how the conflict in Ukraine might affect interest rates and how that might affect housing prices, and brought us full circle in terms of how we might address the housing affordability crisis in LA. We are very appreciative of your time and thank you for the insights you provided.