June-July 2022

June/July 2022

Patterns of Migration During Housing Boom and Bust Cycles

Leo Feler, Senior Economist, UCLA Anderson Forecast

Gregor Schubert, Assistant Professor of Finance, UCLA Anderson School

Economic Update with Leo Feler

- Are we headed for a recession? It’s becoming more likely. The Fed has signaled it will keep raising its benchmark interest rate until data shows that inflation has come down. Only one FOMC member, Esther George, voted against raising rates 75 basis points at the June FOMC meeting, citing concerns about forward guidance and how such an increase would affect households and businesses. Even traditionally dovish FOMC members, like Mary Daly, have turned hawkish. We expect the Fed to increase rates another 75 basis points at its July 26-27 meeting and continue raising rates up to at least 3.50–3.75% by the end of the year. We expect 30-year mortgage rates to remain at approximately 5.5%–6.5% throughout the remainder of 2022 and into mid-2023, which should substantially slow the housing market.

- Because of continued high inflation and the Fed’s actions to slow the economy, we now expect slower growth compared to what we forecasted at the end of May. Real GDP growth in Q2 2022 and for the remainder of the year is likely to be weak as the Fed continues to tighten monetary policy.

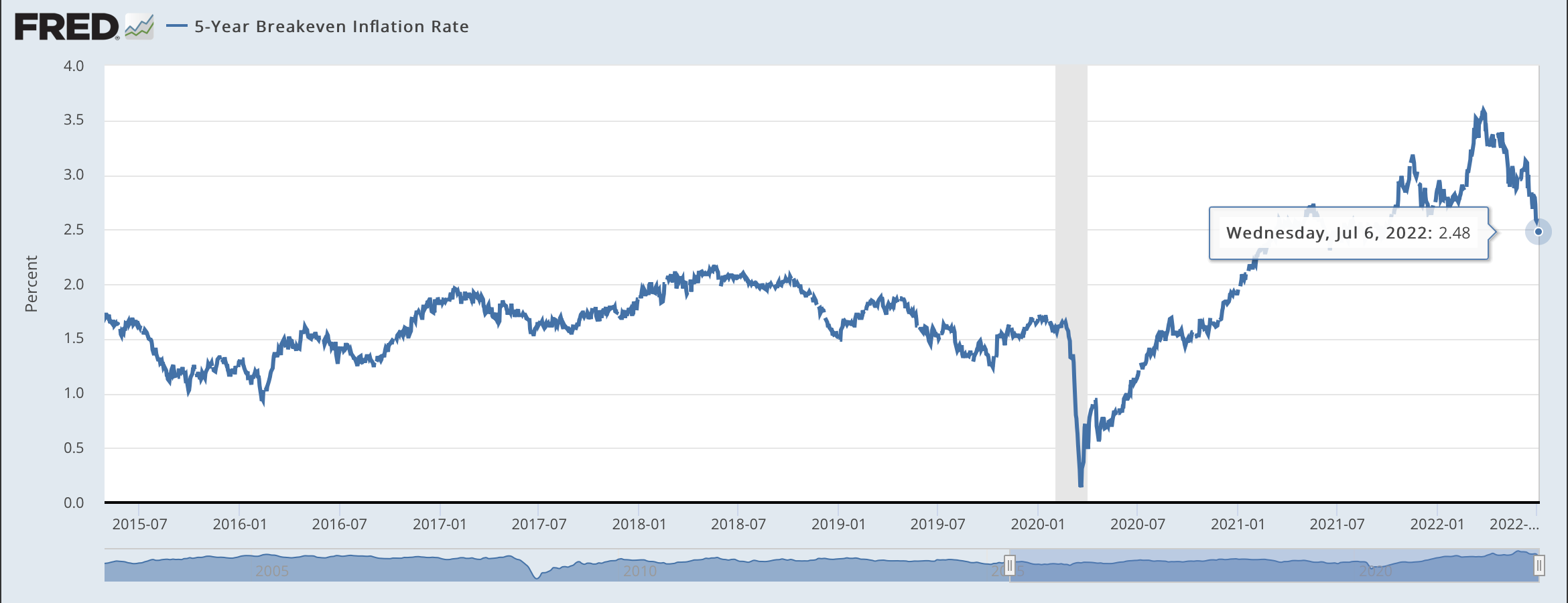

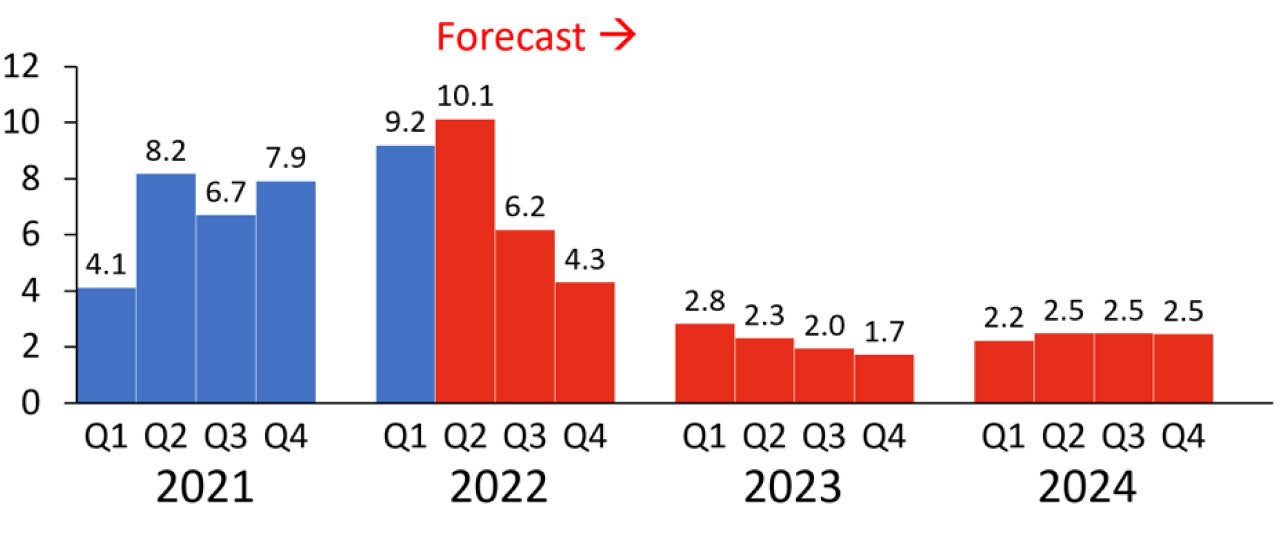

- Commodity prices, including oil, have started coming down, so there are some signs inflation may have peaked, and even gas prices at the pump might start easing. Still, inflation is likely to remain stubbornly high and inflation expectations, measured by 5-year breakevens remain elevated, above 2.5%, as shown in Figure 1. Our forecast for quarterly CPI inflation, at seasonally adjusted annual rates, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Market Expectations for Average Inflation During the Next Five Years

Figure 2: UCLA Anderson Forecast for CPI Inflation, Quarter-on-Quarter Percent Change in CPI, Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rates

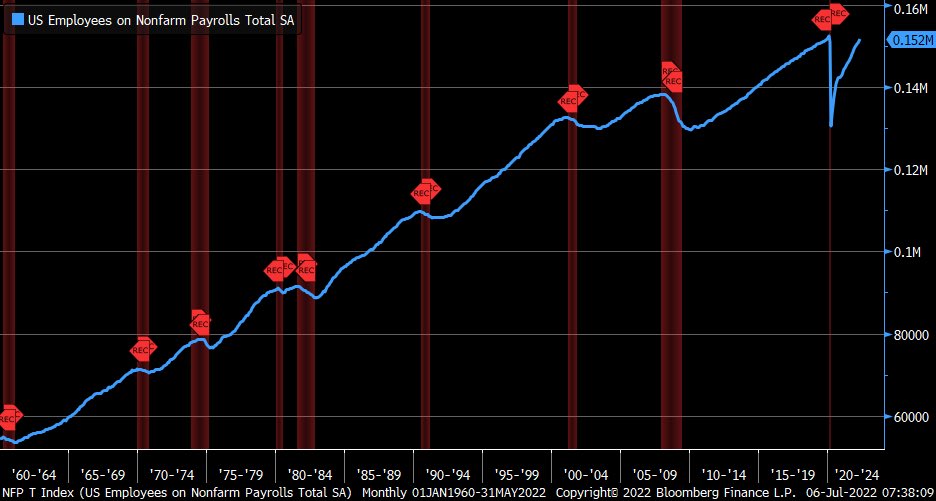

- How can the economy be slowing when employment growth remains strong? And can the economy contract even as employment continues to grow? Actually, changes in employment tend to lag changes in output. Employment often peaks in the middle of recessions, not necessarily before recessions start, as shown in Figure 3. Because hiring and firing is costly, it takes time for businesses to lay off workers in response to a decline in demand. Businesses first tend to pause hiring, then they reduce workers’ hours, and only once there’s more certainty that a sustained decline in demand is occurring do they tend to lay off workers. It’s not inconsistent for employment to keep growing – but at a slower rate – even at the beginning of recessions.

Figure 3: Total Nonfarm Employment and Recessions (Shaded)

Patterns of Migration During Housing Boom and Bust Cycles

Assistant Professor of Finance, UCLA Anderson School

This month, we are pleased to host a conversation with Professor Gregor Schubert, who recently joined the faculty of the UCLA Anderson School of Management. Professor Schubert discusses his research on migration between cities and housing boom and bust cycles and on the effects that large employers have on local labor markets.

Leo Feler: Gregor, I want to talk with you about two of your research papers. The first has to do with migration during housing boom and bust cycles. Can you tell us about this paper?

Gregor Schubert: There are large variations in house price cycles across different areas of the United States. For instance, Las Vegas has really large up and down cycles, while Topeka Kansas does not. At the same time, there is all this news around the role that migrants from coastal California are playing in second-tier cities in the US in terms of driving booms in local housing markets. This paper tries to quantify the degree to which local house prices are driven by spillover migrants from high house price cities that are looking for more affordable housing elsewhere, and thereby driving up house prices in other cities. We see these cascading effects where house prices go up in some cities, that drives out migrants who are looking for more affordable housing elsewhere, which then drives up house prices in those destination cities. We see house prices go up in a synchronized fashion in different cities that have migration links to one another.

Leo Feler: We’ve seen this story during the pandemic about housing prices going up a lot more in places like Boise, Fresno, Nashville, and Austin – a lot of people are leaving expensive coastal cities to move to these locations. Do you have a sense of how Zoom and the ability to work remotely, how this might change some of the patterns that you’ve found so far in your research?

Gregor Schubert: To some degree, the ability to work remotely will reinforce existing patterns. Where previously people were required to live in LA or San Francisco in order to draw a tech hub salary, they’re now able to take a tech hub salary while living in a much more affordable location. That makes the overall package of some of the tech hubs less attractive, because now you can get the same salary with a lower housing cost somewhere else. It makes those housing markets, in relative terms, more expensive than more affordable living in places like Boise. So Zoom and the ability to work remotely leads to somewhat similar dynamics to an increase in house prices in San Francisco: it makes those tech hubs less affordable and drives people to live somewhere else. As a result, we would actually see very similar migration patterns to what we saw before the pandemic, in that people move from expensive cities to less expensive cities. In terms of the patterns we have seen during the pandemic, that seems to play out. People continue to move between the same pairs of cities that they moved to before the pandemic, but maybe at an accelerated pace. This shift toward remote work accelerated this move of some workers out of these expensive places into less expensive places, but perhaps with the added wrinkle that whereas previously you were trying to move to a city that had some kind of industry that you could work in, now you’re slightly less dependent on that. Because you can still retain the job you had in your old city, it doesn’t really matter as much what the industry looks like in your new city, and so you’re more flexible. Maybe there’s a slight shift in where you can go to but I don’t think there are major differences in terms of where people are moving.

Leo Feler: In urban economics, we think about production amenities and consumption amenities. Production amenities means your city offers a good business environment to establish a tech firm, for example. Consumption amenities we think of as being beautiful nature, nice restaurants, great weather – things that consumers want. As people are able to take their tech hub salaries and work in other cities, do we see the pattern of cities that benefit from out migration shifting toward those that offer better quality of life for consumers rather than better productivity for firms?

Gregor Schubert: I think you’re right that to some degree, we would expect things to shift towards people caring more about consumption amenities than productivity. It’s actually surprising to me to what degree the main metropolitan areas we expected to do well before the pandemic continue to do well, in spite of this dynamic. We still see New York, Boston, LA attracting a lot of the young, educated people and having rapidly increasing rents and home prices. I think part of that is actually due to the fact that these cities are not just productive hubs, but they are actually consumption and amenity hubs. LA and New York City are attractive cities to live in even if they aren’t also hubs for the technology, entertainment, and finance sectors. As a result, there are many workers who say, “I don’t have to live in San Francisco anymore, I’m not going to choose to live in Topeka Kansas, but I’m going to choose to live in New York City,” because New York continues to have that attractive amenity bundle. It tends to be the case that those two – production amenities and consumption amenities – go together to some degree.

Leo Feler: What role do local housing policies play in the patterns we see in your research? If Los Angeles had more permissive housing policies and made it easier to build additional housing, how would that change your findings?

Gregor Schubert: You hit on a key variable here. I think the main reason why we see these migrations between cities is that when one city becomes really attractive and productive, it pulls in high income workers of the industries that are booming, and because cities don’t accommodate additional employment with enough new housing – for instance, LA has very restrictive housing policies and a lot of low-density areas that just don’t build enough housing – because of that, it becomes very zero-sum. So when new high-income workers move in, other workers have to move out, and the way that the market ends up clearing is through rapidly increasing home prices that end up pushing some workers out, and those workers then end up migrating to other cities, and that leads to these spillover home price effects driving up home prices in Boise, Las Vegas, Phoenix, and so on, in these connected cities. If LA, for instance, were building enough housing and accommodating all of these inflowing workers by building large multifamily buildings – instead of making it very difficult to build anything beyond a certain level of density – then you’d actually see a smaller increase in home prices. A lot of these incoming workers wouldn’t displace existing residents. You’d just see LA grow in size and density, rather than having this zero-sum dynamic where some workers get replaced by others. I think if LA was more permissive, you’d see a softening of this migration effect. You wouldn’t need migration to balance the scales and get the lower income workers from your city to find more affordable housing elsewhere. You could just find more affordable housing in LA by moving to a different neighborhood or by building enough housing such that prices don’t go up in the first place.

Leo Feler: Is there a difference in the types of individuals who are mobile? We’re talking about high-income, highly educated workers moving in and perhaps lower-income, lower-education workers moving out of coastal cities. Do you have a sense of who is differentially mobile because of a positive or negative economic shock?

Gregor Schubert: In my research, I’ve looked at who is moving between cities. While people have this mental image of retirees moving to Florida or maybe most of the moves to second-tier cities being driven by people retiring, retirements just aren’t a major driver of overall migration. The reason is that retirees in the US just aren’t that mobile. People of retirement age make up less than 10% of all the moves between cities because older people just don’t move as much as younger people. What’s really going on is that the main migration dynamics are being driven by college-educated workers of working age replacing non-college educated workers of working age. I find this pattern where over the last 20 years or so, college-educated workers have moved from less expensive cities to more expensive cities, and non-college educated have moved in the opposite direction. They’ve moved from more expensive cities to cheaper cities in general. You see this pattern even more extremely in the most housing-constrained cities. The more supply-constrained a city is, in terms of housing, the more zero-sum this dynamic becomes. Large inflows of college-educated workers tend to be associated with large outflows of non-college educated workers in these housing-constrained cities.

Leo Feler: During the pandemic recovery, we heard a lot about labor shortages, especially in places like Orange County, San Diego, and Los Angeles. What you’re suggesting is that part of the reason we’re experiencing these local labor shortages is that as higher-income workers have moved in, there hasn’t been enough housing built, so that has displaced lower-income workers, and so we find ourselves with a shortage of lower-income service sector workers in a lot of these cities with restrictive housing policies.

Gregor Schubert: That’s exactly right. To some degree, the shortage of lower-income service sector workers is homegrown in places like LA. In order to attract someone to work in a restaurant, you have to compensate them not just for the effort of working there, but you have to pay them to be able to live in LA. That might mean compensating them for very long commutes in order to get to their place of work or compensating them for the exorbitant rents that are required to live close to the main economic centers in LA. Because we don’t build enough housing, you need to compensate those lower-income workers a lot more in order to attract them to service sector jobs. For some of these workers, the tradeoffs might mean they’re just not willing at all to live in the metro area, which might lead to a shortage of workers. And, it might mean higher salaries at the lower-end of the income scale, which we’ve seen recently.

Leo Feler: Turning now to a different topic, you have a paper looking at employer concentration and how this affects wages. This is really a hot topic right now when we think about competition and antitrust policy, about mergers, and about companies becoming larger. Can you tell us about this paper?

Gregor Schubert: In this paper, my co-authors and I look at the power large employers have over their employees’ wages. There’s an important concern that if there are a few large employers in your local area and in your particular labor market, they can push your wages down because you don’t have a lot of bargaining power. This concern is now starting to play a role in antitrust policy where policymakers are considering whether they should evaluate the impact on local labor markets when they’re looking at a merger between two firms. What we do in this paper is we look at whether or not existing literature defines labor markets the right way, and we propose a new way of thinking about labor markets in this context.

The big issue is, if you’re for instance a barista, we could look at labor markets in your local area for baristas and try to figure out if they are concentrated, and if those employers might have market power over you. But in practice, baristas may be very likely to move into becoming waiters or taking on other service sector jobs, so their labor market is broader than just the narrow occupation of baristas. When we want to think about their overall labor market power and the options they have, we really want to be evaluating all the jobs they are likely to move into that might be part of their choice set.

We use resumes of workers where we can see them move between occupations to infer which occupations are very mobile and which ones are not, and what occupations people are likely to move between. We then use these movement patterns to define for each occupation what the labor market looks like in terms of the choice set of occupations people might be likely to move into. We use this new measure of labor markets to estimate what the effect of employer concentration on wages is.

What we find is that highly concentrated labor markets where there are very few employers in your choice set of possible jobs means that workers have lower wages on average. The effect that your employer can have on your wages are three times larger for occupations that are not very mobile, for workers that are sort of stuck in place and have to take whatever their employer offers them, relative to occupations that are highly mobile. If workers are very mobile, they tend to see smaller impacts of their employers being concentrated.

Leo Feler: We saw during the pandemic recovery a lot of mobility across sectors. We had workers who had been in the restaurant industry suddenly working in transportation and logistics because that’s where there was a lot of demand. Wages in transportation and logistics tend to be higher, and so that’s pulled-up wages in the restaurant sector as well. When we think about something like an Amazon distribution center opening up in a local economy, how does that affect the labor market?

Gregor Schubert: Amazon is a great example for thinking through these dynamics. Both our research and research that other people have done suggest that when Amazon enters local labor markets, they tend to push up wages. For other local employers, Amazon represents competition for their workers. Amazon ends up setting a wage floor that is above the local minimum wage, and as a result, that represents an effective wage floor for other local employers. If your workers can always choose to go to Amazon and get $15/hour, you better offer $15/hour, otherwise your workers are going to leave. As a result, Amazon ends up pulling up wages in local labor markets when they enter.

An important thing to consider is, if Amazon drives other local businesses out of the market, so that smaller employers don’t exist anymore and don’t offer local labor market competition, perhaps in the long run, wage growth will be slower, because Amazon will eventually use its market power to keep wages capped at the local market rate. These dynamic effects in the long run are hard to study because we haven’t seen the long run yet. It does seem that in the short run these positive effects dominate and Amazon pulls up local wages by providing a new option for local workers.

Leo Feler: In certain sectors and markets, have we started to see a critical threshold of concentration affecting wage growth?

Gregor Schubert: In our paper, we show that on average about 10% of workers in the US may see something like 2% lower wages as a result of high employer concentration. In other words, these workers’ wages would be 2% higher if employers were perfectly competing for their labor. We see this particularly in service sector occupations that require some kind of licensing or specialized skills.

For example, among pharmacists or aircraft mechanics, you see very little mobility across different occupations. In these licensed professions, there don’t tend to be that many local employment options that have good use for their skills, so these workers are stuck with their employers, and they earn lower wages than they would otherwise – because of this lack of mobility interacting with concentration of their local employers. However, we have to distinguish this cross-sectional effect, where in the cross-section it does seem pretty clear from our study and other studies that concentration is associated with lower wages, from the dynamic effect over time.

An important question that comes up is: does this explain a decline in wages over time in the US? Here, the answer seems to be no, because while concentration among firms at the national level has gone up, at a local labor market level, overall concentration among employers appears to have gone down over time. Given that concentration has gone down over time in a lot of local labor markets, because more national firms are competing in each local market, that would suggest we should have higher local wages because there is greater local competition among employers. We can’t explain longer-run declines in the labor share or wages using this concentration effect. It’s more important for explaining cross-sectional differences between local labor markets within a time period.

Leo Feler: Gregor, thank you very much for taking the time to do this podcast and for your insightful research.