April-May 2022

April/May 2022

Supply Chains, Ocean Shipping, and Recession Risks

Featuring:

Jerry Nickelsburg, Director, UCLA Anderson Forecast

Vince Iacopella, Executive Vice President, Alba Wheels Up

Leo Feler, Senior Economist, UCLA Anderson Forecast

Economic Update with Leo Feler

-

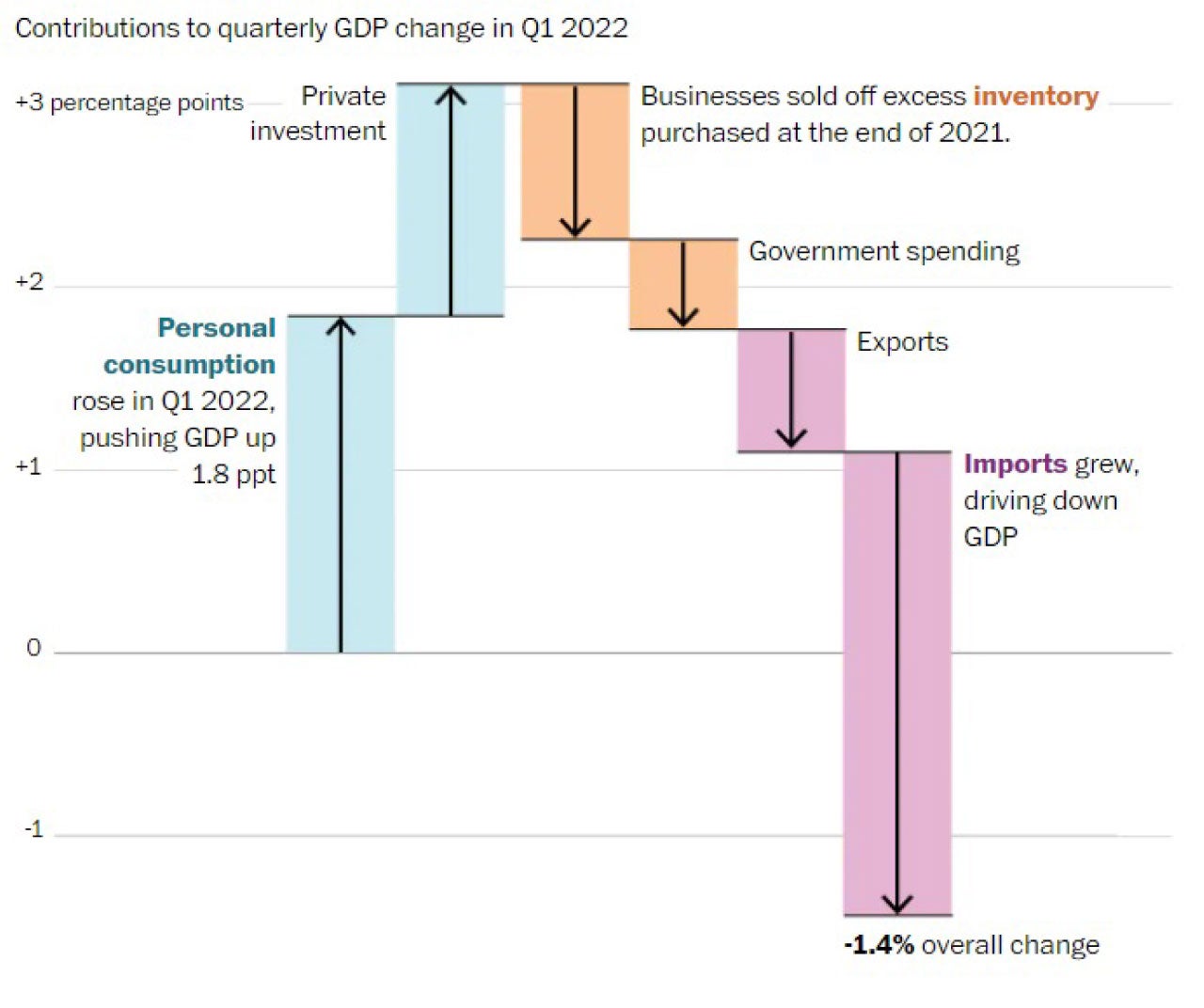

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contracted 1.4 percent at an annual rate in Q1 2022, following 6.9 percent growth in Q4 2021. But despite this contraction, the underlying fundamentals of the U.S. economy were strong. Personal consumption increased 2.7 percent at an annual rate. Investment increased 2.3 percent, led by business investment, which increased 9.2 percent.

-

So why was GDP growth negative? There are three main factors:

-

Federal, state, and local government purchases declined. We don’t expect this decline to continue going forward. It was related to an expiration of pandemic-related programs at the end of 2021.

-

Exports shrank, while imports grew substantially. Thus, much of the consumption growth and some of the investment growth that occurred in Q1 weren’t domestically produced. This means we shouldn’t be factoring in the full amount of consumption and investment growth as “domestic product” since they were not domestically produced. In other words, we need to subtract imports from the GDP calculation. For a full discussion of how GDP is calculated, see this explanation from Noah Smith.

-

Following a strong increase in inventory growth in Q4 2021, inventory growth slowed in Q1 2022. In part, this is because businesses were already able to replenish much of their depleted inventories in Q4, and so they did not have to do as much inventory accumulation in Q1, and in part, this is because recent supply shocks toward the end of Q1, with COVID shutdowns in China and the war in Ukraine, have made it more difficult for companies to continue replenishing inventory.

-

-

The increase in business investment supports our thinking that supply will catch up to demand. Over the past year, the economy has experienced rapid inflation because of too much demand chasing too little supply. This is apparent in the latest import numbers as well, where Americans are consuming more imports and essentially exporting demand and inflation to the rest of the world. As we discussed in our last forecast report, U.S. businesses have been able to pass-on higher prices to consumers. Those businesses that can expand supply will be able to capture greater market share at higher prices. The incentive is for businesses to invest and for supply to increase, which, over time, should bring inflation down.

-

Overall, while the U.S. economy has weakened and will likely grow more slowly as the Federal Reserve increases rates to combat inflation, we view the latest GDP numbers as a one-off dip rather than the beginning of a prolonged contraction. The underlying fundamentals – personal consumption, business investment, and residential investment – remain strong.

Exhibit 1: Contributions to Quarterly GDP Growth in Q1 2022

Supply Chains and Ocean Shipping

Executive Vice President, Alba Wheels Up

This month, our podcast features a conversation with Vince Iacopella, Executive Vice President of Alba Wheels Up. We discuss supply chains and ocean shipping. Below is an edited transcript of the conversation.

Jerry Nickelsburg (JN): Much of the supply chain discussion thus far has been about throughput at the ports, and rail and trucking. An important but sometimes neglected part of supply chains is ocean transport from Asia. Maybe we can begin pre-Covid. Set the stage for us. What was happening pre-pandemic?

Vince Iacopella (VI): I started in Trans-Pacific shipping back in 1987, and so I have over 30 years in this industry. Back in the 1980s, the ports of LA and Long Beach were becoming the gateway for North American markets. Aside from the pandemic, two other important periods for Trans-Pacific shipping would be 2010, when a post-Great Recession restocking depleted inventory, and then again in 2017. The reason I call out these two years is that they were dress rehearsals for what happened during the pandemic, in 2020 and 2021. You hear a lot about systemic issues in Trans-Pacific supply chains. Some are pre-pandemic systemic issues, like the lack of leveraging advanced data, not leveraging all the technology that is available on shipping manifests or load plans, and each ocean terminal and ocean carrier having their own proprietary system with different levels of functionality for data.

You’ve heard a lot in the last two years about ocean carrier policy on equipment – what container can go on what chassis. Also, there are the ever-present labor issues in the ports with contracts and automation. Also, what role has the government and the Federal Maritime Commission played in looking at what one might call unfair business practices. Prior to the pandemic, the largest 10 or 11 ocean carriers grouped off into three consortiums. The reason those groupings were greenlighted by the Federal Maritime Commission was because the narrative over the last 20 years was that the ocean carriers were not making a margin sufficient for their survival. Three years ago, the large Korean carrier Hanjin filed for bankruptcy. Ironically, the Trans-Pacific carriers have made up all of those losses in the last two years. What happened during the post-Covid rush, and the crazy demands for consumer goods that ensued, was that these systemic issues were exacerbated.

JN: Pre-pandemic, ocean-going shipping experienced a technological change with large carriers like Maersk moving to very large freighters such as the Triple-E class with fifty-foot draft and 160 feet beams, which dramatically reduced costs. Is this really the driving force behind the industry’s consolidation and why events like the Ever Given stuck in the Suez Canal have happened? How do these very large freighters affect freight, canals, and supply chains?

VI: The trend on the large megaships happened pre-pandemic as carriers went to a hub-and-spoke system. So now, I’m going to feed cargo into Singapore on smaller vessels, and then onto a huge vessel from Singapore to LA. One of the by-products of these megaships is how long they take to unload. When they would come into Los Angeles it would take five days to unload, which is unprecedented.

There are two issues with respect to the canals, the Suez and Panama: infrastructure upkeep and dredging. Some of our ports, like Seattle, Los Angeles, and Long Beach, are deep. Many, like Oakland, are not. We need dredging for these bigger vessels to be able to load and unload at these ports.

You also raise the margin question with the creation of these large ships. If I go back to 2010 and the Great Recession, there was a move to the zero-inventory model. That is, I’m not going to hold inventory unless I’ve sold or am very close to selling it. We have lived in this kind of zero-inventory environment since 2010. Now, since things are not moving as quickly from Asia and Europe to North America, we’ve seen in the last year or so a reversal of the zero-inventory model. August 2021 was probably the most acute situation, with companies wanting inventory in the United States, Canada, Mexico, or anywhere but on a vessel waiting to berth at Long Beach or stuck outside Shanghai.

JN: Earlier you mentioned that carriers, particularly the three consortia, made back all of their losses and then some, in the last couple of years. Those profits should also induce smaller firms to bring back old ships. Are we seeing that?

VI: We have seen that. And we’ve also seen smaller carriers, like Wan Hai and carriers that used to be just inter-Asia, adding Ensenada or Long Beach into their rotation. We saw some small carriers go back into the North American market. Recent data suggest there is an effort to bring more equipment back online.

JN: I imagine it takes a long time to bring a ship back that’s been retired.

VI: Yes, and my only caveat is not all of these ships were retired in the traditional sense. Is a ship really retired when it needs to come back in six months, or was it really idle in Singapore where it could come back in right away? Those are some of the questions asked about how quickly capacity has been brought back. I think that’s a moot point now, because even with more capacity, the ocean carriers are all filled up. So now the motivation is to add still more capacity. I would wonder, though, how much motivation there really is since additional capacity is going to drop the price.

JN: Along those lines, the President commented that the three consortia were holding up prices in an oligopolistic non-competitive sense, and that was one reason for higher consumer prices.

VI: I don’t think you need to be an economist to know that if your operating costs rise significantly, that probably needs to be reflected in your sales price. Although, in the summer of 2021, a lot of companies were not able to do that because they were locked into contracts with retailers and they ended up with margin erosion. It’s pretty much an untold story that not all of those price increases were passed on to consumers. I think there has to be some truth to the fact that significantly rising supply chain costs, especially on the order of 12% or 14%, is going to result in higher prices along the way. The craziness about 2021 was having ocean freight prices rise five-fold, not 20% or 50%, but 500%. However, there is an argument that prior to the pandemic, prices might have been too low and maybe they needed an adjustment. But I think five times is probably too high. Do we ever go back to anything called “normalcy” is an open question. When we come out of pandemic-related practices and buying habits, and maybe consumer demand is not as robust as it is now, what is the price of ocean shipping? I think it will be somewhere in the middle of where it was pre-pandemic and where it is today. I think companies will have to get used to higher Trans-Pacific prices than they were used to pre-pandemic, but at the same time, they can’t support the price increases that happened in August 2021 and January 2022.

I want to talk about what Senator Warren and others have been mentioning for a long time. The argument was that three groups, or consortia, were needed for survival. Also, before the pandemic, decisions about where vessels go and how often they go were no longer made in the United States. Out of 11 carriers, at least one might have been flying an American flag, but today none are headquartered in the United States. That brings in a geopolitical questions and national security question about supply chains. If an ocean carrier takes 20% of capacity and ships it to Europe instead of North America, they don’t need anyone’s permission. I think what Senator Warren and the Biden administration were expressing was something that many people noticed years before, that obviously the US loses a lot of leverage if we don’t have a single US-based carrier. I may be wrong on this, but I think when President Kennedy formed the Federal Maritime Commission in the early 1960s, it was about making sure that we had at least one US flag carrier. Today, there aren’t a lot of decisions being made in LA, New York, or DC. So, even before the pandemic, people saw some threats to the US not having a dog in the fight, so to speak.

JN: Let’s turn to the containers these ships are carrying. The ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach threatened to implement fines for empty containers staying on terminal property. Why would ships bringing in 7,000 containers not leave with 7,000 containers? What is the container issue that causes them to be left in one place, rather than circulating to where they’re needed?

VI: So I’m going try to unpack this, because it has many facets. First, I think we all need to realize that when my company or my customer orders a container in China, we do not choose the chassis company, we do not choose the terminal it comes out of. All of that is something we buy, when we buy the ocean freight. So, when you get to Long Beach, Oakland, Los Angeles, Seattle, or New York, the chassis issue is really Joe’s problem, across the harbor, and the wheels issue is really Jane’s problem across the harbor. The customer bought all those services from the ocean carrier. That’s why when you hear ocean carrier policy brought up – those are decisions that at a policy-level can change. Also, there is the box rules. That means that this ocean carriage container can only go on this company’s chassis, and that’s it. If that chassis is not available, that container just sits. These are policy issues that can be addressed.

I will talk about the idle container fee. I’ve talked directly with the leadership of the ports. There was a lot of concern about the fee. The fee basically was threatened but not implemented. In talking to the leadership of LA and Long Beach, at the Trans-Pacific Maritime meeting in Long Beach, in March, I think we all have a little bit better perspective. I don’t think it’s genuine to say that the ports never intended to implement the fee. I think there might have been an intention there. But there also might have been an intention to see what could be done with just the threat of a fee. Thirdly, as a middle-market company, who serves middle-market customers, no surprise here that the fee would have been exponentially more detrimental to middle-market companies. For instance, if you were a big box shipper, if you were a big retailer, you might have owned your own chassis. You might have had a 24/7 operation. All of those things are more conducive to getting containers off the pier more quickly. But if you were a middle-market company that was still relying on the ocean carrier for some of these silly rules regarding boxes, chassis, containers, hours of operation, the night gates not being fully utilized – then that middle-market company, which was my customer, they didn’t have control to avoid the fee. That was our big pushback. The second big pushback, which is the most obvious, is that the port imposes the fee on the ocean carrier, and the ocean carrier immediately sent notices out that they were going to impose the fee on the customers. So, here we have this transfer of the fee from the carrier down the chain to the customer. And, the middle-market customer had no control over that. So, we had a big problem with the fee in the beginning.

Here’s the post-script: the post-script is that the data seems to show that 20-30% of the containers that were stuck on the pier prior to this may have been moved by those companies that did have control over chassis and night gates and 24/7 operations. If that’s the case, one can make the argument that it was effective, in that moving about one-third of the containers off was better than nothing. Ultimately, the fee wasn’t imposed, so no fees were passed onto the middle-market users. It does raise another issue, I believe. It raises the issue of how bigger players have maybe more choices in the market. We want to get to a place with advanced data, and better ocean carrier policy, where small and medium-sized companies have more of a competitive role in some of these practices that can help get goods out more quickly.

JN: You’ve described systemic problems in the industry. The recent supply chain interruptions should lead to structural changes. What are your thoughts on where this is going?

VI: Looking at this, there are a couple of pilot programs popping up. Full disclosure, I’m sitting in Southern California, so I’m rooting for our region, of course. But I really think that the ports of LA and Long Beach have been out front on this, because they were aware of these systemic issues before. Obviously, the Biden administration has put a lot of pressure on both ports because 40% of ocean cargo arriving in the United States comes through those ports. But even before the pressure from the administration, many see this as an opportunity to finally look at these issues and come up with something durable, something that leverages technology, something that really shares data. Labor issues are a bit more complicated and will be more complicated come July. I think this window of opportunity is now open. What will change, I think this data has been out there for many years and leveraging advanced data to plan better is something you’re going to see right away. A lot of our companies are doing it already. You also may see the Federal Maritime Commission with more enforcement authority. There is a bill passed by the House that is in the Senate which would give the Commission more oversight enforcement authority over the ocean carriers. So maybe, better data, more advanced data, better technology systems, and probably more enforcement oversight by the federal government.

JN: Vince, thank you for joining us for the April/May podcast and sharing your insights on the changing oceang-oing freight industry.