Structured modeling was developed as a comprehensive response to perceived shortcomings of modeling systems available in the 1980s. It is a systematic way of thinking about models and their implementations, based on the idea that every model can be viewed as a collection of distinct elements, each of which has a definition that is either primitive or based on the definition of other elements in the model. Elements are categorized into five types (so-called primitive entity, compound entity, attribute, function, and test), grouped by similarity into any number of classes called genera, and organized hierarchically as a rooted tree of modules so as to reflect the model's high-level structure. It is natural to diagram the definitional dependencies among elements as arcs in a directed acyclic graph. Moreover, this dependency graph can be computationally active because every function and test element has an associated mathematical expression for computing its value.

Using a model for any specific purpose involves subjective intentions. Structured modeling makes a sharp distinction between the resulting user-defined "problems" or "tasks" associated with a model, and the relatively objective model per se. A typical problem or task has to do with ad hoc query, drawing inferences, evaluating model behavior with specified inputs, determining a constrained solution, or optimization, and requires applying a computerized model manipulation tool ("solver"). For certain recurring kinds of problems and tasks, these tools are highly developed and readily available for incorporation into a structured modeling software system.

The theoretical foundation of structured modeling is formalized in Geoffrion [1989a], which presents a rigorous semantic framework that deliberately avoids committing to a representational formalism. The framework is "semantic" because it casts every model as a system of definitions styled to capture semantic content. Ordinary mathematics, in contrast, typically leaves more of the meaning implicit. 28 definitions and 8 propositions establish the notion of model structure at three levels of detail (so-called elemental, generic, and modular structure), the essential distinction between model class and model instance, certain related concepts and constructs, and basic theoretical properties. This framework has points in common with certain ideas found in the computer science literature on knowledge representation, programming language design, and semantic data modeling, but is designed specifically for modeling as practiced in MS/OR and related fields (Sec. 4 of Geoffrion [1987]).

An executable model definition language called SML (Structured Modeling Language) fully supports structured modeling's semantic framework (Geoffrion [1992a]). Other languages for structured modeling also exist, as noted later. SML can be viewed in terms of four upwardly compatible levels of increasing expressive power. The first level encompasses simple definitional systems and directed graph models. The second level covers more complex extensions of these, spreadsheet models, numeric formulas, and propositional calculus models. The third level encompasses mathematical programming and predicate calculus models with simple indexing over sets and Cartesian products. Finally, the fourth level covers sparse versions of the above plus relational and semantic database models.

The following figures from Geoffrion [1987] show an SML schema (third level) specifying the general structure of the classical feedmix model, and sample SML elemental detail tables specifying model elements. The latter, together with the schema, yield a specific feedmix model instance.

&NUT_DATA NUTRIENT DATA

NUTRi /pe/ There is a list of NUTRIENTS.&MATERIALS MATERIALS DATAMIN (NUTRi) /a/ : Real+ For each NUTRIENT there is a MINIMUM DAILY REQUIREMENT (units per day per animal).

MATERIALm /pe/ There is a list of MATERIALS that can be used for feed.Q (MATERIALm) /va/ : Real+ The QUANTITY (pounds per day per animal) of each MATERIAL is to be chosen.UCOST (MATERIALm) /a/ Each MATERIAL has a UNIT COST ($ per pound of material).

ANALYSIS (NUTRi, MATERIALm) /a/ : Real+ For each NUTRIENT-MATERIAL combination, there is an ANALYSIS (units of nutrient per pound of material).

NLEVEL (ANALYSISi., Q) /f/ ; @SUMm (ANALYSISim * Qm) Once the QUANTITIES are chosen, there is a NUTRITION LEVEL (units per day per animal) for each NUTRIENT calculable from the ANALYSIS.

T:NLEVEL (NLEVELi, MINi) /t/ ; NLEVELi >= MINi For each NUTRIENT there is a NUTRITION TEST to determine whether the NUTRITION LEVEL is at least as large as the MINIMUM DAILY REQUIREMENT.

TOTCOST (UCOST, Q) /f/ ; @SUMm (UCOSTm * Qm) There is a TOTAL

COST (dollars per day per animal) associated with the chosen QUANTITIES.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Space does not permit a proper description of SML's syntax, but a few hints are as follows. Schemas are organized as a tree of paragraphs whose leaves are the genera and whose interior nodes are the modules. The boldfaced part of each paragraph is the formal definition of the genus or module, as the case may be, and the rest consists of documentary comments about the formal part which are informal except for conventions about the use of underlining and upper case. The formal definition of a genus paragraph begins with the name of the genus, a parenthetical statement of definitional dependencies (if any), a slash-delimited statement of genus type, a colon-announced statement of data type if an attribute genus, and a semicolon-announced mathematical expression called a generic rule if a function or test genus. The formal definition of a module paragraph consists only of its name. Note that a schema is always specified independently of any problem or task that might be posed on it. A common problem associated with the above schema is to find values for all Q elements such that all T:NLEVEL elements evaluate to true and the value of the TOTCOST element is minimal.

The structure and sequence of the elemental detail tables are determined procedurally from the schema. Each table is named, has column names that usually coincide with genus names, and has a row for each element of the corresponding genus.

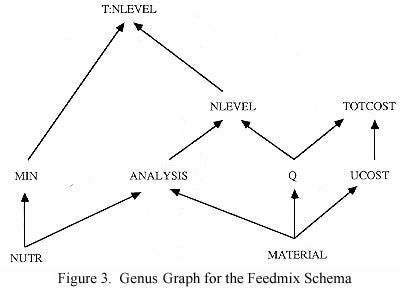

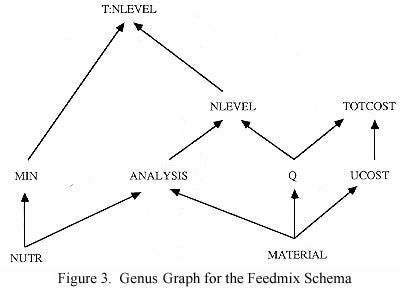

The next figure, also from Geoffrion [1987],

shows the so-called genus graph associated with the above schema.

It represents definitional dependencies at the level of genera.

Owing to the design of the underlying semantic framework and of SML itself, SML-based modeling systems can have certain features often lacking in modeling systems of more conventional design, including:

Some additional features of FW/SM are:

The following sections review and comment on recent research and open research opportunities relating to structured modeling. These are divided into four main categories: improved modeling languages, approaches to model integration, extensions designed for simulation modeling, and three topics falling under implementation strategies and technologies.